How N.L. became the life (and death) of the party

We’re cutting through the undergrowth to find out why our political parties feel dead — and what might liven them up

Hello dear voter!

In Part 1 of this field guide to Newfoundland and Labrador’s distinct political system, we focused on how easily our three major political parties — Liberal, Progressive Conservative (a.k.a. Tory), and New Democrat — could be mapped along the coordinates we use for talking about politics in general: left or right, federalist or nationalist, technocratic or populist. As we discovered, while there are clear distinctions between each party, the Liberals and Tories are pretty flexible as far as their principles go depending on their proximity to state power. (We have yet to see how the NDP would hold up in that crucible.)

Whether you view this flexibility as a feature or a bug depends on where you stand. On the one hand, to quote Rowdy Roddy Piper in They Live, “the middle of the road is the worst place to drive.” On the other hand, to paraphrase a tweet from former Telegram reporter Peter Jackson in response to me quoting that line at him, “the ruts are deepest in the left and right lanes.”

We can put this vehicular metaphor into overdrive and spin out a few useful questions. What are the official (and unofficial) rules of the road? What kind of driver is behind the wheel? What is the make and model of each car? What are we going to find if we check under the hood? In other words, how exactly do political parties in this province work?

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

Buckle up — the next part of this crash course will take us over a few potholes.

Let’s get this party started

One of the basic premises of small-L liberal democracy is the idea that there are too many people, who are much too busy living their lives, for everyone to be directly involved in every single aspect of governmental decision-making. Instead, roughly every four or five years they cast votes to decide who will represent their interests in a parliament (from the Old French, parlement — ‘to discuss’).

Our House of Assembly is descended from the British (or “Westminster”) parliamentary system, an elaborate institution that has been evolving over 800 years to balance the power of the Crown and the interests of its various subjects in determining how society should be governed. Its rules and procedures are complex and arcane, so bear with me as I attempt to distill the basics.

Everyone elected to parliament decides among themselves which members will form the governing Cabinet that takes responsibility for directing and administering the various powers of the state. The leading member of the Cabinet — primus inter pares, “first among equals” — becomes the premier (or prime minister). Legislative decisions are made when a majority of elected members agree on them, typically (though not always) by a slim “50% + 1” cutoff. If a majority of representatives can’t agree on particularly important decisions (e.g. the annual budget), the government is said to have “lost the confidence of the House” to govern. The parliament then (usually) dissolves and a new election is called.

Strictly speaking, you don’t need political parties for any of this. But organizing representatives into disciplined voting blocs based around shared values and/or personal loyalty to a leader makes this process significantly more efficient, effective, and predictable — which is why parties emerged in the first place over the course of the 19th century. The party with the most seats gets the first opportunity to form a government and its leader becomes the premier.

Hypothetically, it would be totally possible to send 40 individuals with no partisan affiliation to the House so they can deliberate freely. There are non-partisan parliaments in Canada — in Nunavut, Nunatsiavut, and the Northwest Territories — that operate on a consensus model, where all members participate together in weekly caucus meetings with cabinet (as opposed to separate and adversarial government and opposition caucuses). Those legislatures are typically much smaller — Nunavut is the largest with 22 seats — and they have fewer jurisdictional responsibilities than provinces.

A viable non-partisan House of Assembly would mean a radical restructuring of our provincial political system. It would require at least 21 candidates fully committed to this shared position, organized enough to get elected in their districts, and disciplined enough to form government and execute their vision without factional infighting. In other words, it would require the creation of a political party for the purpose of abolishing political parties. I’m sure you can see the irony here.

I do not subscribe to the folk wisdom that all partisanship is always bad. A competitive party system can actually be very healthy.

Political parties organize more than just politicians: they organize ideas, values, resources, desires, and goals. When they are functioning properly, they are vehicles through which non-politicians can connect with their representatives, articulate their wants and needs, shape the direction of public policy, hold parliamentarians to account, and participate in the work of collective self-government. A vibrant party is an institution with a life of its own beyond the immediate interests of its leadership; it magnifies the power of its ordinary members into something bigger than any individual. Parties are a vital part of the democratic system and keep citizens engaged in the process in between elections — if they are functioning properly.

A dysfunctional political party is a different story. These parties organize ideas by condensing them into thought-terminating clichés and focus-grouped slogans imposed from the top down. The only connection its members are permitted to form is blind loyalty to the party and its leader. Otherwise it is deaf to anything its members have to say, deferring instead to the demands of its biggest donors. The party apparatus exists as a vehicle for personal advancement, and every relationship within and towards it is purely transactional and self-interested — assuming an apparatus exists at all outside of election season.

Rather than being kept in check by contact with its ordinary members, dysfunctional parties tend to become disconnected from the public altogether. For some party officials and donors this too may be more a feature than a bug, but it’s not particularly healthy for democracy.

I don’t think it’s very controversial to suggest the political parties in this province are dysfunctional. It’s more useful to think about what environmental and social conditions might have warped them out of shape in the first place. As the twig is bent, so grows the tree — in our case, three stunted tamaracks on a sea cliff growing sideways.

The political is personal

A lot has changed in the seven decades since Newfoundland and Labrador joined Canada, but our party system isn’t one of them. As S.J.R. Noel writes in the magisterial (if dated) Politics in Newfoundland, both pre- and post-Confederation parties are best understood as “loose networks of people held together by personal relationships, old loyalties, and the multifarious rewards and deprivations that [governing party] ministers have it in their power to bestow.” In the context of this system, MHAs are “expected to barter personal favours and services in exchange for electoral support.”

Not exactly an arrangement conducive to the common good, or even the Canadian constitution’s more modestly boring core values of “peace, order, and good government.” But tracing these issues back to their origins underscores that like most institutions in our province, our political system was created less by deliberate design than structural necessity. It was an adaptation to survive, if not thrive, among adverse conditions.

As the only “developed” settlement on the island for a long time, St. John’s dominated the political and economic life of the country in an even more dramatic fashion than it does today. Each MHA was the sole intermediary and liaison between the people in their district and the central government in town. There wasn’t much of a state to administer at either the national or local level, so MHAs functioned as a kind of regional super-mayor who fielded all the demands and grievances of their constituents — and also personally determined who got the government grants, contracts, appointments, and any other public money that flowed into the district. Everything was held together by patronage and personal connections.

Noel points to a disapproving passage about Newfoundlanders’ approach to democracy from the memoirs of Ralph Williams, colonial governor from 1909 to 1913, that is worth quoting in full:

“Electors give no thought to general principles of policy of which they know nothing, and for which they, for the most part, care nothing. For them it is simply a case of the ‘ins’ and the ‘outs.’ […] They regard their member as one who has to look after their personal interests in every detail. He must be ready to watch over them when they are ill and get them free medical treatment; he must get them tickets for the seal fishery, employment on the railways, free passes from place to place, billets for their sons and daughters, and must even strive to sell their fish above market price at the bidding of any ignorant or mischievous agitator. In fine, there is nothing too ridiculous for electors to expect of their member, and failure in any single case may send back a constituent to [their] outport […] to become the centre of a clique resolved to displace the member from his seat in Parliament. […] It has been bred in their bones that it is their duty to strive to extract favours from a government whose sole idea they believe to be a desire to deprive them of their rights.” (Ralph Williams, How I Became a Governor, 1913: pp. 411-414)

Setting aside Sir Williams’ snobbery, there are two things worth noting about this passage. The first is that it fails to recognize the way that this is adaptive behaviour: in the absence of anything resembling state capacity, MHAs had to take on this outsized role in their constituents’ lives because there was nobody and nothing else to provide these kinds of services. It’s also very difficult to know or care anything about “general principles of policy” when you are caught in the immediacy of cyclical intergenerational poverty. Megan Gail Coles makes an elegant all-purpose counterpoint in Small Game Hunting at the Local Coward Gun Club: “Why does the Newfoundlander [insert problem here]? Poverty. Poverty. Poverty. Fuck!”

The second thing about this characterization is that it remains broadly true more than a century later. If you don’t believe me, spend a morning listening to Open Line.

Or, alternatively, consider an example from the current provincial election: the premier’s satellite office in Grand Falls-Windsor, one of many innovations by the Honourable Dr. Premier Andrew Furey. The Tories charge that this is little more than a make-work project for Liberal Party loyalists to extend the premier’s personal influence into the jurisdiction of the local (PC) MHA’s constituency office. The Liberals counter by pointing out that because of their direct link to the premier’s office, the staff there are able to help connect more constituents with medical care, employment opportunities, and other social and legal services than they would be able to access otherwise.

I would submit that both of these perspectives are true, and that they underscore the fact that political power in this province is accessed and exercised primarily on the basis of the personal networks and connections bound together by each party.

Our political parties don’t organize values or shape policy or engage citizens or drive democratic participation. There is no party infrastructure for any of that stuff and there is no material incentive to create it. Parties are instead held together by unlimited corporate and union donations, the magnetism of the leader’s personality, and inertia. Their main purpose is to determine which elite clique needs to be petitioned for personal or commercial advancement based on their proximity to power. They are closer to hockey fandoms than instruments of governance: an endless tug-of-war between Habs and Leafs fans while a couple of guys in Bruins jerseys stand on the sidelines looking sad.

The most important thing to understand here is that in Newfoundland and Labrador, the political is personal. This is the ideology that all our parties share whether they consciously recognize it or not.

Play stupid games, win stupid prizes

Another way of framing this is that we actually only have two parties — Government and Opposition — who swap colours every decade or so.

There are real differences between the Red and the Blue teams, of course. Each one represents different networks of people with idiosyncratic familial, historical, professional, or ideological reasons for falling into one camp or the other. But they are different in the same way that McDonald’s and Burger King are different. The Whopper and the Big Mac are qualitatively different meals, but they’re both still hamburgers from a fast food chain. Maybe someday we’ll try A&W — their beef is advertised as grass-fed, without hormones — but that’s not really a radical change in our diet.

Everything is shaped by the structural forces of the larger dysfunctional system. The end result of all this — underdeveloped party institutions held together by charismatic personal authority, load-bearing MHA constituency offices powered by personal favours, and unregulated financial contributions from the companies bidding on state contracts — is a political system characterized by chronically short-term thinking and petty personal striving. It creates a public life fundamentally oriented around scheming.

This obviously includes both direct and indirect personal gain for politicians and party loyalists — like cabinet ministers secretly giving themselves bonuses, say, or the Honourable Dr. Premier abruptly quitting politics for medicine and immediately finding himself on the corporate board of a literal gold mine. But it also covers our proud cultural heritage of gambling public money on questionable get-rich-quick development schemes. In no particular order, here are some recent examples off the top of my head: the garbage-burning power plant in Lewisporte; selling the Stephenville airport to the Monorail guy from The Simpsons; the Canopy Growth grow-op in White Hills going up in smoke; the Bitcoin mining operation in Labrador going bust; Muskrat fucking Falls. Personally, I also would put money on eventually adding Atlantic salmon aquaculture, green hydrogen, AI data centres, and the Upper Churchill MOU to this long and painful list. Unfortunately, in this province, you will rarely go broke betting against the government.

This is, of course, a very old story in our colony of unrequited schemes. S.J.R. Noel writes in the conclusion to Politics in Newfoundland that “flights of fancy about [Newfoundland and Labrador’s] ‘vast economic potential’ […] [were] used to justify the expenditure of public funds on a variety of highly dubious private development schemes […] [because] outside capital [cannot] be attracted […] without extraordinary guarantees and concessions by the provincial government. And the terms which investors are able to extract are typically so severe as to make the investment of dubious benefit to the community.” The book was published in 1971, but the assessment still holds up 50 years later.

What I want to suggest here is that this story — or cyclical maladaptive pattern, if you prefer — keeps repeating itself because it is baked into the rules of the game. Its mechanics were devised haphazardly a long time ago in order to cope with social, technological, economic, and administrative constraints that no longer meaningfully exist. It’s not so much that the game is rigged as the rules are dated, broken, and increasingly unplayable without some heavy patching. This is why it feels like our governments are locked into losing: because as long as we play the partisan game handed down to us, they are.

It doesn’t actually have to be this way. It is totally within our power to change the rules and give this bleakly repetitive story a new ending. But the caveat is that you have to win the game in order to change it, and its current setup self-selects the players least suited to fix it.

It’s their party and they’ll cry if they want to

Provided we continue on our course, it’s not hard to see where things are going. This has been an extraordinarily low-energy provincial campaign. The central campaigns are a mess — both Team Government and Team Opposition seem to be out of ideas, out of juice, and very visibly phoning it in. There are good candidates across every party but they are left more or less to wage their own district-by-district dogfights occurring in near total fog of war. Nobody looks like they are having a good time. And why would they? As my comrade Simon Pope put it, “leading a political party in this province is a lose-lose situation: either you don’t become the premier, or you do.”

The energy has been trending downwards for a while now. Campaigns are increasingly bloodless, cynical, demoralized and demoralizing. Both politicians and the public are tuning each other out. All of this spells serious trouble, and it didn’t start with the writ drop on Sept. 15.

As Raymond Blake observes in The End of Politics? Political Campaigns in Newfoundland and Labrador, if you bracket out its Covid-related chaos, 2021 was the most anemic election Newfoundland and Labrador has ever seen — rivalled only by the one in 2015 and, presumably, however many elections are still to follow. Our democracy has been trending in the wrong direction for a while.

“2021 was a campaign of hopelessness […] [where] the most remarkable feature […] is voter apathy, perhaps the greatest threat to a functioning and dynamic democracy,” Blake writes. “When citizens choose not to vote because they have lost interest in campaigns […] it is troubling. That citizens cease to exercise their franchise because they are apathetic may be […] the first step to imperilling their democracy and ending politics, at least formal electoral politics.”

Voter apathy is not an issue unique to Newfoundland and Labrador. The long arc of North American history is bending towards breakdown and the world trembles in all directions. Our home here is also touched by this — the intensification of the opioid epidemic, the housing crisis, and ecological catastrophes like wildfires spring immediately to mind — and the financial outlook for the province is bleak. It’s understandable why people turn away from engaging with a grim collective life and instead cocoon themselves inside their personal comforts and concerns. But this points to the responsibilities of good political leadership: the onus is on politicians to give people reasons to show up.

Unfortunately, our current party system rewards and perpetuates the deadening of political life. Even leaving aside the obvious conflicts of interest it creates, unlimited corporate and union campaign donations mean there is no incentive for parties to meaningfully engage individual members or even the general public.

The only people our provincial leaders are ever in conversation with are the sycophantic donor class in EnergyNL and the St. John’s Board of Trade. It shows. We are seeing the results in real time: beleaguered governing and opposition parties with nothing to offer except hollow promises to rearrange the chairs on the Titanic and a sly wink that their guys will get you a better seat in the lifeboat. It’s amateur hour at the local Legion, and they’re scraping the bottom of the barrel.

The NDP is a different beast than either parliamentary wing of the business lobby, so they’re dysfunctional on another level. When you can bank on a few massive union cheques to fill the campaign war chest no matter how long the electoral odds, you don’t have much incentive for party-building either — even if labour can never, ever outspend capital. Factor in the distinctly leftist coping strategy of interpreting chronic defeat as proof of moral superiority and it’s easy to see why some people prefer power-tripping on righteous indignation from the nosebleed section. Sometimes success is more terrifying than failure.

One weird trick to fix your provincial democracy (doctors HATE her!)

Newfoundland and Labrador faces serious problems, and the way our political parties work is a major contributor to many of them. Historically, the intensely personal dynamics of our party system have continually produced and reproduced insular cliques of governing elites whose inability to look beyond themselves always gets them (and us) into trouble. Blake cites historian David Alexander’s wonder about the “inadequacies of the clique who dominated the economic and political life” of NL, while S.J.R. Noel suggests that the closed nature of those cliques “ensured that positions of power and responsibility would be inherited, often by those of weak character and limited intelligence, rather than earned by those of lowly origin but high ability.” This calls to mind the second law of thermodynamics: in an isolated system — and what is a clique if not an isolated social system? — disorder will only increase. Turmoil, as usual.

There is no way of one-shotting this longstanding sociological problem. But there is an easy, straightforward first step we can take that will go a long way towards making things better: we can ban big money from politics.

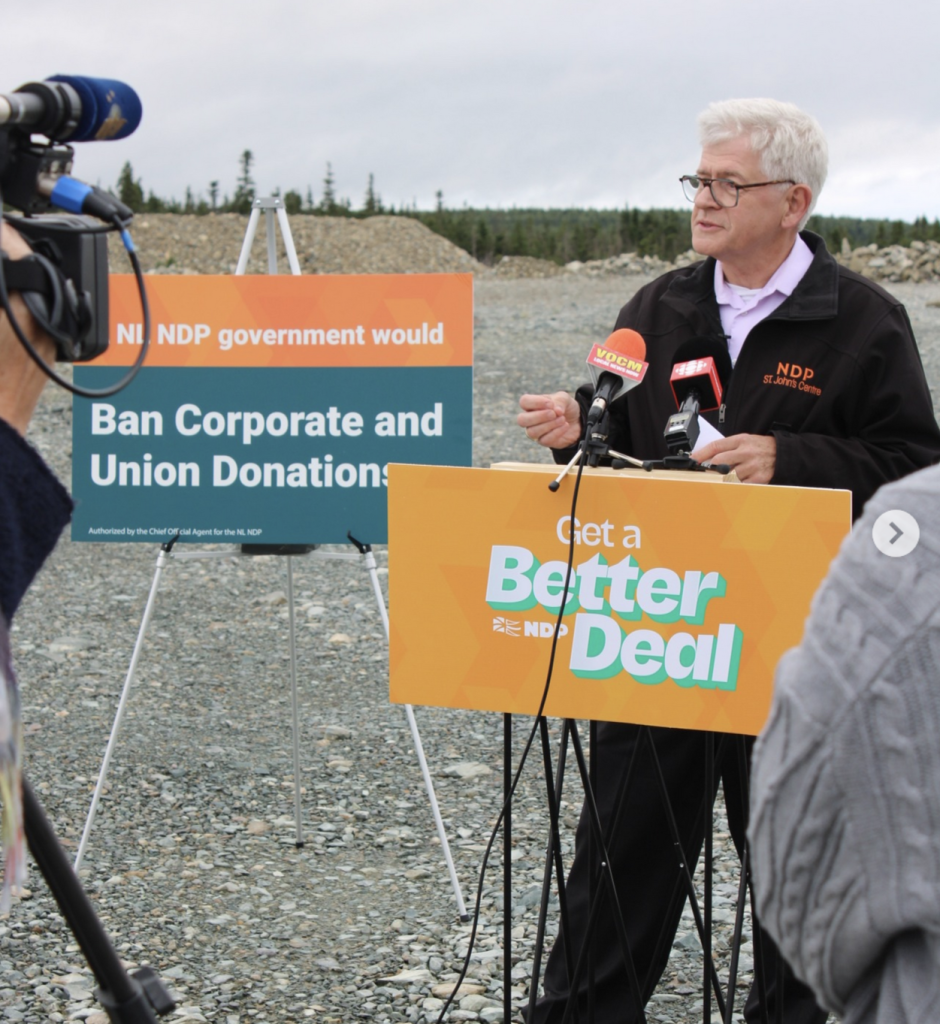

Jim Dinn deserves earnest praise for promising to ban all corporate and union donations and capping individual donations at $1,750, even if it comes a day late and a dollar short from the party least likely to enact it. Tony Wakeham gets a quarter point for at least shrugging, “we’ll look into it.” John Hogan should be booed in the streets for totally blowing it off.

Campaign finance reform is not a silver bullet. It’s not a miracle cure. It will not immediately cast out any demons or wake us from the nightmare of Newfoundland history. It might take a while to see meaningful effects. But even if the best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago, the second best time is now. Regulating money in politics is a really, really easy thing we can do to immediately start improving our situation.

Almost every other jurisdiction in Canada already does it. The City of St. John’s does it. And it will actually force politicians to come talk to you and listen to you and try to help you with your problems, because they won’t just need your one vote every four years: they will need your money (and your time) on an annual basis. It allows for more fresh air and fresh blood to circulate through the body politic. The parties will be incentivized to draw you in, articulate your ideas, inflame your passions, connect you with like-minded others, and empower you to do more for your community than drop a ballot in a box and hand over the keys of state power to people who don’t know where they’re going — or even how to drive.

This concludes our guided tour through democracy in Newfoundland and Labrador. It’s not perfect, but it belongs to you — if you can keep it. It really is as simple as “use it or lose it,” even if ‘simple’ is not the same thing as ‘easy.’ Overcoming the inertia of learned helplessness is painful, and the work of self-government is hard. But if our history teaches us anything, it’s that the only thing harder is the alternative.