What would it look like if N.L. enshrined housing as a human right?

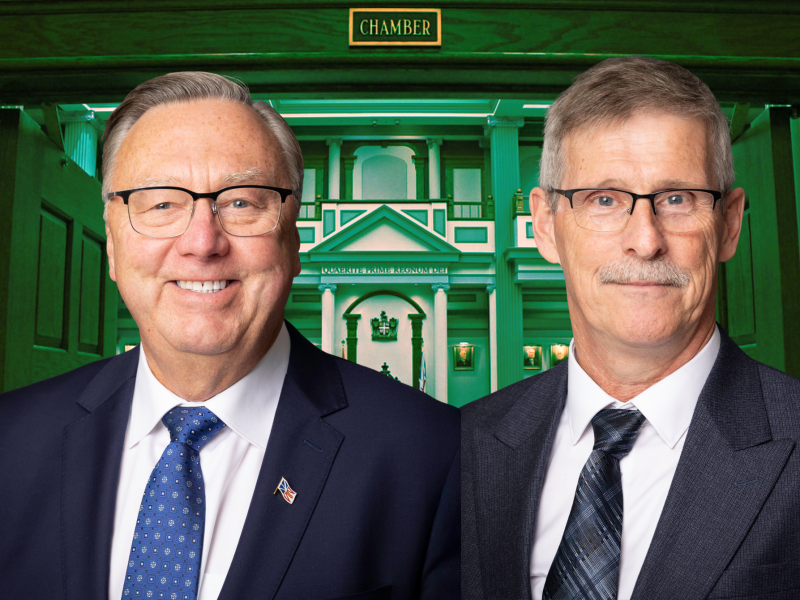

Premier Tony Wakeham told The Independent housing is “absolutely” a human right

Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Tony Wakeham has affirmed his belief that housing is a human right.

Following his Oct. 29 swearing-in as the province’s 16th premier at Government House in St. John’s, Wakeham said housing is “absolutely” a human right in response to a question from The Independent. But the new premier didn’t answer whether he would enshrine that right in provincial legislation.

Daniel Kudla, an associate professor in the sociology department at Memorial University, says no province or territory has followed the federal government’s lead in recognizing housing as a human right in law. If the Progressive Conservatives were to enshrine the right to adequate housing in legislation, it would be “a very significant step.”

Sherri Chippett, executive director of the Newfoundland and Labrador Housing and Homelessness Network, agrees. Chippett says if housing were recognized as a right in provincial law, the provincial government would be legally obligated to ensure people have access to adequate housing.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

The right to adequate housing has long been established in international law, beginning with the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and then in 1966 with the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

In 2019, the Canadian government brought in the National Housing Strategy Act, recognizing adequate housing as a fundamental human right. From that legislation came the creation of a federal housing advocate, who has recommended provinces and territories follow the federal government’s lead and “adopt provincial or territorial legislation recognizing the human right to adequate housing as defined in international law.”

Although many jurisdictions include safeguards for people who face housing denial or discrimination, none have stand-alone legislation protecting housing as a right. Prince Edward Island’s Residential Tenancy Act references Canada’s commitment to a United Nations treaty, which recognizes adequate housing as a human right but contains no provisions that uphold the right.

In 2021, then Nova Scotia NDP leader Gary Burrill brought forward a private member’s bill to enshrine housing as a fundamental right in that province’s legislation. The bill was defeated in a 29-24 vote.

In March 2024, the Canadian Human Rights Commission called on provinces and territories to enshrine the right to adequate housing in their laws, something all jurisdictions have failed to do.

What would housing as a right look like?

Kudla says the provincial government can opt to enshrine the right to adequate housing in law using different approaches, or a combination of them. Internationally, some of the most successful strategies include implementing a program-based right to housing or establishing a legally enforceable right to housing.

If the provincial government were to adopt a program-based right to housing, it would mean supporting residents in securing housing. Kudla says a similar program in Finland has found success. The Finnish government has a legal duty to take active steps to ensure residents have access to adequate housing by creating conditions that enable everyone to obtain it.

Finland focuses on a housing-first model and national programs which guarantee access to permanent housing with support services. To prevent homelessness, Finland requires stronger cooperation between all levels of government, NGOs and municipalities. It emphasizes early intervention and more affordable housing. The country’s homelessness has significantly and continuously decreased since 2008.

Kudla says that if Finland’s model was applied in Newfoundland and Labrador, “the duty would be on the province to take active steps to ensure people have access to adequate, affordable, safe housing.”

The second approach would replicate Scotland’s Anti-Homlessness Measures, which include a legal right to housing. This means that to help prevent homelessness, the government must work with individuals to resolve their housing issues—for example, by negotiating with landlords, accessing benefits, or finding alternative housing. If someone becomes homeless, the local authority has a duty to provide temporary housing and assist in finding permanent housing.

The difference between the two approaches is that, “as a legal right, it’s enforceable through the courts, whereas a program right is not protected by the courts, but it’s something that is to be progressively realized through public policy.

Why do Canadian jurisdictions shy away?

Kudla says provincial governments shy away from working to enshrine housing as a right because it would increase accountability, require measurable outcomes, monitoring, evaluation and enforcement of plans. “It would allow people experiencing homelessness, for instance, or people evicted by landlords—it would allow them to challenge governments that fail to uphold that right,” he says.

The government’s inaction in addressing housing includes a lack of community housing development, Kudla adds. In a July 2025 report, Breaking the Bottleneck: Catalysts for Expansion in NL’s Community Housing Sector, the Community Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador and Annex Consulting found the province has just 1,000 community housing units—roughly 0.3 per cent of the total housing stock—compared to the national average of 4 per cent.

Canada’s housing system is complicated by the way responsibilities are divided among federal, provincial, and municipal governments. The federal government provides funding and sets specific national frameworks, while provinces and territories have much of the on-the-ground responsibilities and municipalities typically handle zoning, permitting and local implementation. This can cause confusion and lead governments to shift blame to other levels of government.

Chippett says provincial housing as a right legislation could help strengthen intergovernmental commitments by reinforcing the National Housing Strategy Act and housing as a human right. “This could allow the potential for provincial funding and partnership opportunities while influencing other provinces and municipalities to follow with changes to the legislation.”

She says she has met with multiple levels of government about homelessness, only to be referred to a different level of government. “You’re speaking with municipalities and they say, ‘Oh, that’s a provincial issue,’ or you’re speaking with the provincial government and, ‘That’s a federal issue.’”

Additionally, provincial legislation recognizing housing as a right could address systemic barriers through more coordinated access to resources, Chippet says, “with a greater focus on prevention, including investment in non-market housing, rental supports, and wrap-around services.” This, she adds, can lead to long-term savings by reducing costs associated with healthcare, emergency shelters and policing and the justice system.

The provincial housing crisis

Since the pandemic, the province has faced a worsening housing crisis, with rising home prices and a decline in affordable housing options. According to the Consumer Price Index, Newfoundland and Labrador experienced the highest rent increase in the country over the past year, at 7.8 per cent, surpassing Canada’s overall average of 5 per cent.

According to the Everyone Counts: St. John’s Homeless Point-in-Time Count 2024, at least 1,400 people experienced homelessness in 2024, an increase from 900 in 2022. Among those surveyed in 2024, 64 per cent identified high rent as a key reason for their homelessness. Funded by the federal government, the Point-in-Time Count offers a one-day snapshot of homelessness in a specific area.

Housing is a social determinant of health, Chippett says. “[It] is foundational to a person’s well-being, a community’s well-being and the overall province’s well-being. Everyone needs to recognize that right.”

Chippett says the province’s housing crisis isn’t inevitable. “People know what we need […] to be able to address the issues,” she says. “So it’s just that things are not moving, and it seems like everybody’s kind of working in silos. “

Provincial New Democratic Party Leader Jim Dinn says Wakeham’s acknowledgement of housing as a right is important, but concrete measures must support it. “If the premier believes housing is a human right, and it’s not just empty words, then he will do what is necessary and enshrine it in legislation.”In its election platform, the PCs vowed to increase “the number of people whose housing costs do not exceed 30 per cent of their incomes – giving everyone the opportunity to have a safe and suitable home within their budget.” The party said it plans to 10,000 new homes in the province over five years, and to “aggressively repair or replace uninhabitable NL Housing units.”

The party has not committed to implementing rent controls as other provinces have, nor has it indicated it will enshrine adequate housing as a human right.