Defining Newfoundland and Labrador’s political system in 2025

Can standard dichotomies like ‘left and right’, ‘nationalist and federalist’, or ‘populist and technocratic’ help us understand politics in the province?

Have you ever gazed out over the roiling political landscape of Newfoundland and Labrador and thought to yourself: what fresh hell is this? Who are all these people and what are they talking about? How am I supposed to know who to vote for when all the parties seem the same? And why can’t the NDP ever seem to get it together and win a provincial election?

You are in luck! The Independent is proud to present this general guide to understanding politics in Newfoundland and Labrador. We’re hopeful it will serve as a roadmap through as many provincial elections as it takes for the federal government to repossess the House of Assembly as part of the inevitable bankruptcy proceedings.

We’re stripping it down to the fundamentals here. The simplest way to orient politicians and parties in this province is along three spectrums.

The first is the classic “left-right” spectrum, which is all about how people distribute social power and economic resources. The second is the federalist-nationalist spectrum, which relates to the place of our province in Canada. The third is the technocratic-populist spectrum, which is about who has the authority to make government decisions.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

Broadly speaking, these are dimensions we share in common with the rest of Canada or other parts of the world, so we will explore those before diving into the feature that makes democracy in Newfoundland and Labrador unique: its underdevelopment.

Newfoundland and Labrador’s political system is the most enduring aspect of a distinct society and culture that has eroded and evolved over the seven decades since Confederation in 1949. Whether this is good news is a judgment left to the reader.

Left, right, and upside down

Building on the work of political theorist Corey Robin in The Reactionary Mind, I’m going to propose a very simple rubric for understanding “Left” and “Right” as the cardinal directions of all modern political life. They are the two poles bracketing all the different ways you can answer the question(s) of how (and why) society should be organized regarding the distribution of power and resources, and the sorts of things the state should (or shouldn’t) do to achieve those ends. The directional shorthand dates back to the early days of the French Revolution: the revolutionaries who wanted to constrain or abolish the king’s absolute power sat on the left of the National Assembly, while those who wanted to uphold it sat on the right.

Over the ensuing two centuries each pole of this dynamic has been layered over with many additional meanings that it is beyond the scope of this article to explore. Most simply, we can define leftist politics as those that tend to actively equalize or eliminate hierarchical relationships (whether social, political, economic, and/or “natural”), while rightist politics tend to either leave those hierarchies in place or actively reinforce them. The so-called centre, then, is the space taken up by those who seek to reconcile or compromise between these two opposing drives. Often this boils down to a question about where we draw the line in defence of hierarchy and differential treatment.

In 2025, most of us accept that men and women should be equal at work and at home, or that no racial group should have special privileges over any other. But what about the dictatorial authority of a boss over their workers while they’re on the clock? How about the sovereign rights of parents over their children within the sacred structure of the nuclear family? Should we always privilege human interests over animals and the rest of the natural world? Also: does wielding the power of the state as a means of dismantling hierarchies reproduce the problem of hierarchy elsewhere? Unless you’re a committed anarchist, some hierarchies are more defensible than others — at least some of the time.

So on the spectrum from left to right you have communists and social democrats, conservatives and fascists, and in the middle you will generally find all kinds of small-L liberals whose historically-conditioned individual interests lean more one way or the other. (American political discourse muddles this because they use “liberal” as a synonym for “leftist”, but these are historically and conceptually two very different categories.)

Another common way for this spectrum to be framed is between “progressives” and “conservatives” — that is, between people who want to change elements of society to be more just, inclusive, equal, and/or rational, people who would prefer minimal or no changes to the status quo, and people in the middle who make a virtue out of compromising between these two positions. It’s not an exact fit for the Left-Right continuum, but in our present climate people tend to use “progressive” to indicate left- or liberal-coded ideas.

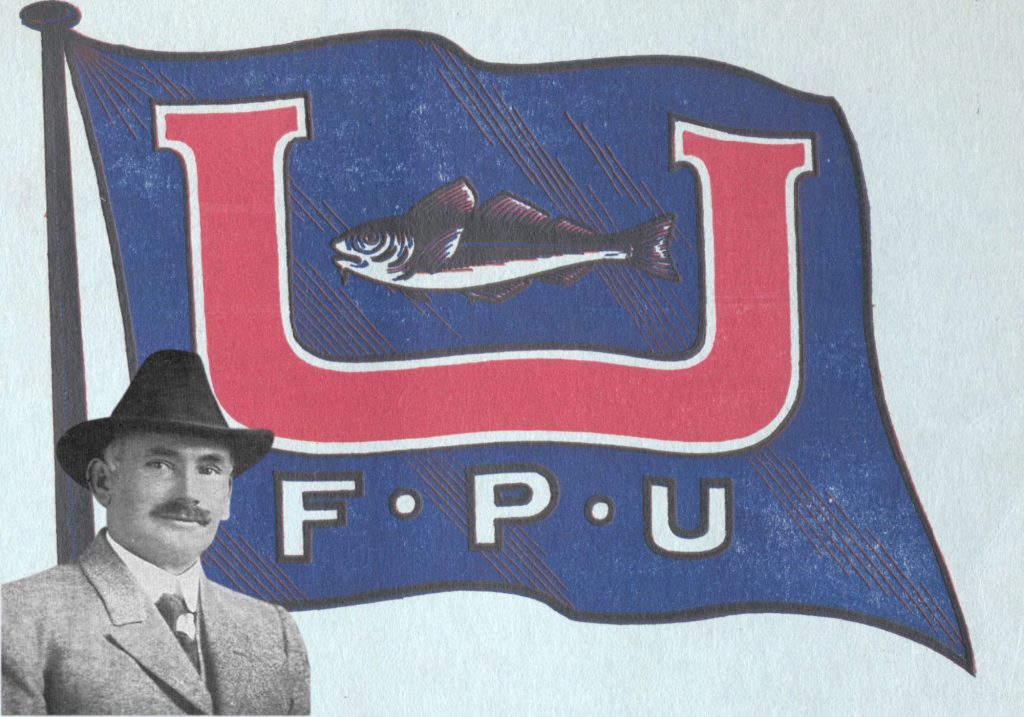

The dynamic tension between Left and Right hasn’t been a major driving force in Canadian politics for many years. It was never a major factor in shaping political life in Newfoundland and Labrador except for a brief moment in the early 20th century when William Coaker and the Fisherman’s Protective Union tried to build new economic, political, and social institutions for rural working people as an alternative to those dominated by merchants in St. John’s. (Spoiler: it was an unhappy ending for the Unionists.) For better or worse, we are (mostly) all small-L liberals: we are individualists who prioritize personal autonomy, private property rights, a more-or-less regulated capitalist market economy and a more-or-less robust welfare state to fill in the gaps. The Liberal, PC, and New Democratic Parties all agree on these points and only ever quibble about tinkering on the margins of “more-or-less”.

One way of interpreting this is that there is no “ideology” in NL politics. I would argue that’s not quite true: all politics is “ideological”—that is, a set of values and goals organized around a particular understanding of how human society operates. It’s just that in NL, everyone is singing from the same hymn book—very often from the same song, if not the same verse—and so we recognize ideology about as clearly as a fish recognizes water.

Given this general atmosphere of ideological alignment, the most impassioned political contests in NL tend to hinge on being for-or-against specific development projects or a leader’s personality.

Our place in Canada

As a federation, Canada’s Constitution Act, 1867 considers each province as co-sovereign with the federal state. (This does not apply to the territories.) The result is that the Canadian political system is riven by the fundamental tension of balancing the interests of the national government with the interests of its 10 provincial counterparts. This isn’t always easy, as Quebec and Alberta routinely demonstrate. But how close a province should hew to the tempo set by Ottawa and how far it should march to the beat of its own drum, is a question that gets revisited every provincial election — and often in-between.

The federalist-nationalist dichotomy is arguably the most clearly defining division in provincial politics here because our party system was initially organized according to where the party’s members stood on joining Canada.

Newfoundland and Labrador is unique among the provinces in that it was—for a hot minute, largely on paper—a separate sovereign Dominion before joining Canada in 1949. Despite a long and colourful list of political parties in the House of Assembly—Liberal, Conservative, Liberal-Conservative, Liberal-Reform, Liberal-Labour-Reform, People’s Party, etc.—all of them evaporated with the end of democracy in the early 1930s. New parties needed to be created when it was restored in 1949 and rather than start from scratch or dig around in the dustbin of history, we looked instead to the mainland.

Confederation occurred with a Liberal government in Ottawa, so the victorious confederates under Joey Smallwood—who had promised Newfoundlanders access to the bounty of the Canadian welfare state—were more than happy to rebrand themselves as Liberals to signify their alignment. The defeated anti-confederates regrouped as the Progressive Conservatives and proceeded to sit in opposition for 20 years. The left-leaning Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, which eventually became the NDP, arrived in the late 1950s (and wouldn’t win a seat until 1985).

Since 1949, the general rule is that the Liberals tend to be federalists who prioritize national unity and wrap themselves in the Canadian flag while the PCs tend to emphasize provincial autonomy and indulge in more chest-thumping Newfoundland nationalism. So on one end you have Joey Smallwood giving endless speeches about how Confederation is “God’s greatest gift to Newfoundland,” and Danny Williams pulling down the Maple Leaf from every government building on the other—or Brian Peckford fighting federal overreach in Canada’s new 1982 constitution while Clyde Wells torpedoed the 1990 Meech Lake Accord in order to preserve his vision of a united Canada.

It doesn’t always line up perfectly. Joey also threatened to take Newfoundland back out of Canada while in a spat with PC Prime Minister John Diefenbaker; when Kathy Dunderdale succeeded Williams she played much nicer with Stephen Harper in order to secure a federal loan guarantee to finance Muskrat Falls; Andrew Furey began his premiership by talking up his close personal friendship with Justin Trudeau and ended it by attacking the prime minister relentlessly about his signature carbon tax. It’s as much a see-saw as a spectrum, and these are the exceptions that prove the rule.

It’s harder to pin the NDP down. On the one hand the NL NDP is organizationally tied to the federal NDP and draws most of its political strength from labour unions—many of which are also pan-Canadian organizations. On the other hand the provincial NDP tends to be overrepresented among the creative class and cultural workers, and historically speaking few things electrify an artist’s soul like the romance of ‘The Nation’.

Certainly there is a strong left-nationalist streak running through a lot of party rhetoric, but in reality the NDP has never really had a coherent position on the “national question” because it has never been close enough to power here to need one. Then again, considering that neither Liberal nor PC governments have ever been coherent on it either, the emotionally-charged vagaries of Newfoundland’s “national question” might be a feature rather than a bug.

‘The voice of the people is the voice of God’

One of the most distinguishing features of political life in North America right now is what we might call the polarization between technocracy and populism. In its purest form, technocracy—literally, “rule by expertise”—holds that managing political and economic affairs is so complex it should ideally be handled by technical experts, because the general public is often ignorant of its own best interests. Populism is an inversion of this and holds that the (rarely defined) “common man” is basically good and noble but is endlessly thwarted, if not oppressed, by an out-of-touch and corrupt governing elite that justifies itself in the name of “expertise.” For a fun Obama-era satire of the technocrat-populist tension, you can just watch any episode of Parks & Recreation where city officials attend a public forum.

Some theorists have argued that populism and technocracy are actually complementary, in that both positions emerge from a breakdown in the legitimacy of democratic institutions. Unfortunately, most discussions about this are held in academic journals behind heavy paywalls. I can only hope the irony isn’t lost on any of the authors.

Populism can come in both left- and right-wing flavours, but the latter has an overwhelming presence and power in the current historical moment; just ask Donald Trump. Technocracy is often presented as being “beyond politics” or non-partisan—a core part of its appeal. But there is no place “beyond politics” when it comes to questions of how power is allocated and governance is practiced, so technocracy is a form that can launder all manner of left- or right-wing ideological projects and presuppositions. Insofar as we are all small-L liberals now, so too are our “non-political” experts; Mark Carney, the most explicitly technocratic politician Canada has ever seen, cut his teeth as a financier slitting throats for Goldman Sachs.

This dynamic has coloured a lot of Newfoundland and Labrador’s political history. The British resisted granting Newfoundlanders responsible government in the 19th century because they didn’t think we had the emotional or intellectual maturity to manage it. The political crises of the 1920s—where successive governments chaotically lurched from one spending scandal to the next, betting the house on dubious resource development schemes and racking up a calamitous national debt in the process—was eventually taken as evidence by voters that they were right.

We are the only polity in the world to voluntarily relinquish democratic self-government in peacetime—though not without considerable pressure from Canadian bankers and our British overlords, who pioneered a novel form of bureaucratic dictatorship from 1934-1949 called the Commission of Government. And despite the many revolutionary socioeconomic changes Confederation ushered in, the Dominion’s dysfunctional democratic machinery remains largely preserved in amber. As a result, the Newfie vox populi speaks through a thick populist accent.

In tandem with other parts of Canada (and globally), the Liberals tend to skew technocratically while the PCs have more of a populist streak—though, again, it’s hardly black and white. Smallwood effectively leveraged a rural populist insurgency for two decades to support a technocratic administration meant to “drag Newfoundland into the 20th century,” until, ironically, he lost touch with the changing popular sentiments of a new generation. Joey is often the exception that proves the rule, but it’s also worth recalling that the first thing Dwight Ball did after his 2015 election was set up a website for crowdsourcing policy ideas to address the provincial debt. “Communist Revolution” was the most popular choice, which may explain why the Liberals joined the national trend of outsourcing their policy-making to private consulting firms.

PC premiers like Peckford and Williams, meanwhile, could rouse Newfoundlanders to support them by picking fights with various elitist or out-of-touch governments in Ottawa. It’s always better to focus voter ire towards the bastards upalong so they don’t notice the ruling class capers in St. John’s. But like the Liberals, Tories too can play both sides as it suits them—lest we forget that it was craven and unpatriotic to question the “world-class experts” who brought us Muskrat Falls.

The technocrat-populist division in this province has sharpened considerably in the last five years. Andrew Furey called the 2021 election seeking a strong mandate to enforce the potentially unpopular policies forwarded to him by the Greene Report—a panel of experts assembled to study the province’s economic problems, free from the fickle whims of the voting public. His premiership was explicitly technocratic: he overtly identified with the interests of the business class and tech industry, and often appeared genuinely frustrated that he couldn’t simply rule the rabble by decree.

John Hogan hasn’t been premier long enough to pin him down on this one way or the other. But we can probably take the saga of the Sugar Tax as a barometer on populist sentiment.

In 2022 the Furey Liberals introduced a modest 20-cent per litre tax on sugar-sweetened beverages as a means to curb Newfoundlanders’ heroic consumption of Pepsi (or at least raise some money to cover the associated healthcare costs). Taxes are never popular, and it was routinely denounced by PC opposition leader Tony Wakeham as an affront to the food security of low income Newfoundlanders who would presumably die if they had to pay an extra 40 cents per jug of corn syrup. (There was no tax on diet soda.)

To the extent the tax was evaluated, it appears to have been effective in reducing sugar consumption. Hogan’s very first act as premier was to cancel it anyway. But this was probably less because of any principled commitment one way or the other as much as trying to score easy points by cowing to the anger of a crowd.

Because they are rooted in the labour movement—which advances and defends the interests of the working-class majority against exploitation by a much smaller number of bosses—the NDP has a deep left-populist streak. This is strengthened in our province because they have always been relegated to the opposition, which naturally encourages amplifying popular complaints against the out-of-touch scumbags in power.

The experience of NDP governments in other provinces suggests getting elected tends to take some of that edge off. But it might be a while before we get to see whether or not that phenomenon would play out the same way here.

So far we’ve covered how to understand NL’s political system in terms of global and national categories — i.e. how we broadly understand politics everywhere. In Part 2, we’ll delve into the highly unique aspects of political life that you will find nowhere else but here — for better and for worse. If you subscribe to our free newsletter, we’ll let you know as soon as it’s out!