Memorial’s Geography of Neglect: From Decay to Transformation

Decades of austerity have left Memorial’s buildings crumbling and its people sick, but beneath the mould and rats is a deeper story of land and labour — and a chance to transform the university from a site of neglect into a democratic, life-giving institution

The mould hit first — sharp, sour, clinging to my clothes long after I’d left the office. Doctors told me to stay away. The building, they said, was making me sick.

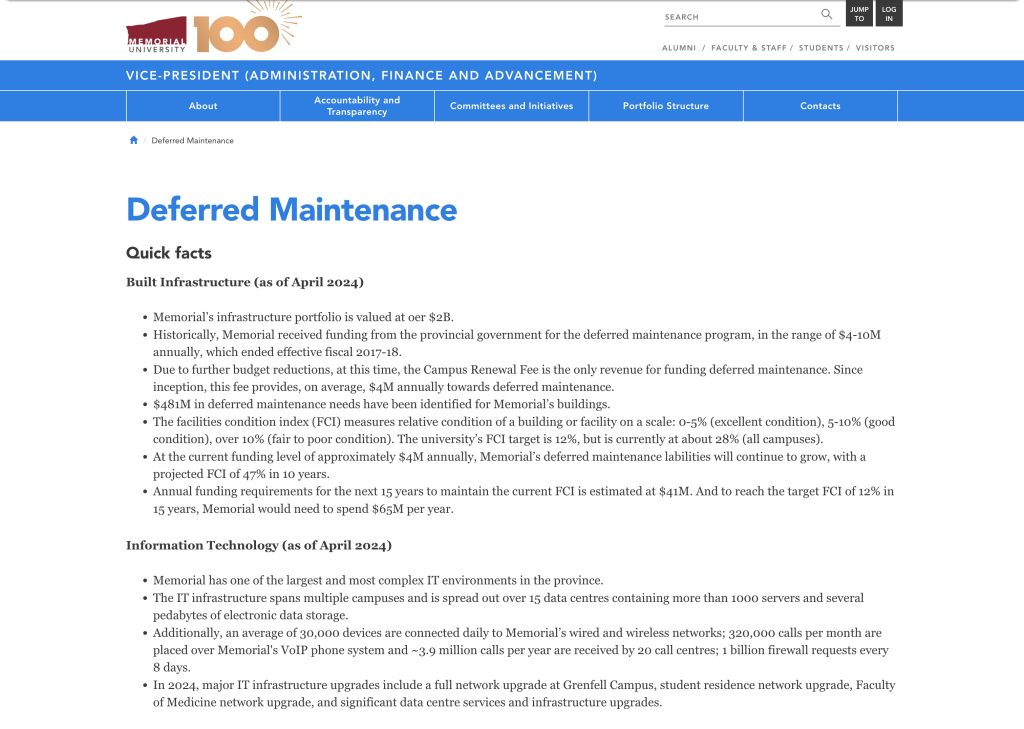

That building — the old Science structure — is still very much in use. Students take lectures there. Staff and faculty work there. And it is literally making some people sick. Other buildings have similar stories of illness tied to over half a billion dollars in deferred maintenance. At the opening of the $347-million Core Science Facility, the Dean of Science said — without a hint of irony or an ounce of empathy — that the old building had been built before Watson and Crick’s discovery of DNA in 1953, but that this new one was “set for many discoveries.” For those of us still teaching and working in the “pre-DNA” building (it was actually built in the 1960s) — with its mould, asbestos, leaks, rats (and not the albino variety used in labs), and crumbling infrastructure — the comment was a gut punch.

The Geography Department was once promised a move to a renovated building — a promise repeated by successive presidents — but that has never happened. Instead, improvements come in one-offs, granted to those who manage to make enough noise in the media, rather than as part of a plan for healthy and equal conditions for all. The same is true across campus: other buildings are also suffering from more than $500 million in deferred maintenance. While classrooms and offices crumble, managerial positions keep expanding, even as student numbers drop, faculty and staff are not replaced when they retire or leave, and employees are laid off. This is not neglect by accident; it’s a governance strategy.

The political contrast was just as stark. The new facility opened with the premier and federal MPs on hand for photo-ops. It contains no shared classrooms or laboratories and has a 16 per cent utilization rate. Meanwhile, some students still learn in deteriorating rooms and some faculty and staff still work in unsafe offices. Even science majors are taught in the old science building, since the new Core Science Facility has no large lecture theatres. The message could not be clearer: some knowledge, and some bodies, are worth hundreds of millions; others can be left to rot.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

I returned to Newfoundland in 2012 for my dream job in geography, leaving a tenured Canada Research Chair position in Ontario because I wanted to be home and contribute to my own province. My parents both worked at MUN, in the medical and nursing schools. I grew up around these buildings in the 1980s when they were far better maintained. Today, they bear the marks of decades of underfunding and neglect.

Austerity is not the weather; it is, as political economist Mark Blyth has written, a political choice — one that research shows harms public institutions and deepens inequality. It’s the same logic I documented in Managed Annihilation: An Unnatural History of the Newfoundland Cod Collapse: those at the top multiply; those who do the work are cut back; the living system collapses in plain sight.

The cost is personal. My mould illness forced me into physical isolation, cut me off from the shared social life of campus, and stalled my career. Students attend lectures in unsafe rooms. Staff spend their days in hazardous offices. Even if you don’t have an office in the old science building, you’ll likely have to leave the core science building to teach there at some point. This isn’t just about buildings — it’s about the relationships, trust, and shared governance a university needs to survive being stripped away on purpose.

What’s almost never named is what holds the campus up: land and labour. Colonialism and capitalism work here as a braid, not as separate strands. Colonialism seizes the land, turning living territories into extractable property. Capitalism exploits the labour that works that land — whether in fishing grounds, oil fields, or the knowledge economy of a university. MUN’s capital projects follow this braid: investing heavily in prestige infrastructure tied to commercial partnerships, while the everyday spaces where most students learn and most workers labour are left to degrade.

Labour here includes the visible work of teaching, research, and technical maintenance, and the often-invisible reproductive work: cleaning, mentoring, emotional support, volunteer committees. Both are exploited — one as “productive” and the other as “support” — yet both are essential to keeping the place running. Increasingly, MUN relies on per-course and contractual faculty — precarious work that extracts intellectual labour without providing job security. The same austerity that leaves roofs leaking has stripped away funding for students and families, eroding the university’s role in supporting social mobility.

Breaking the land-labour braid starts with more than official acknowledgments. It starts with vernacular maps — lived, oral, relational geographies that name the histories official maps erase and chart other futures. Juniper House — home to the Indigenous Student Resource Centre — is one such map. Indigenous students and their allies fought for years for this space and continue to navigate and negotiate the colonial-capitalist campus every day. Nestled between buildings and roads named for colonial figures like Cabot, Gilbert, and Elizabeth, Juniper interrupts the official geography with a counter-map of its own.

It’s not just a refuge from harm — though the clean air and welcoming kitchen matter. It’s a moral, democratic, and practical prototype for the kind of university we actually need. Here, people meet over tea and meals, hold informal discussions, and build the trust that institutional hierarchies erode. The Learning to Unsettle Newfoundland and Labrador Geographies student group gathers with Chief Mi’sel Joe and author Sheila O’Neill to examine how colonial capitalism has shaped land, labour, and knowledge here — and to imagine governance rooted in reciprocity, not extraction.

This pattern is not unique to MUN. The Core Science Facility mirrors Muskrat Falls, a massive public expenditure that transferred wealth to private contracts, championed by government, while basic services were cut or outsourced. Both are examples of industrial colonialism — predatory formations that strip wealth and decision-making from communities.

If MUN wants to call itself a public university, it must act like one. That means healthy, safe spaces for learning and working; free tuition as a genuine public good; ending the “core/non-core” hierarchy that treats some knowledges as disposable; material redress for Indigenous communities whose lands and languages have been taken; and recognition and fair compensation for all forms of labour, paid and unpaid.

It means solidarity between unionized and non-unionized workers, students, and unemployed people — all of whom have an interest in the university’s survival as a truly public institution. And before any new funding flows in, it means removing decision-making power from an appointed board of governors and a swelling management class, and placing it in the hands of the people who actually make the university run.

We shouldn’t aim to “restore” MUN to its past; we should aim to remake it into something it has never been — a university where governance is democratic, land is held in reciprocity, and labour is valued beyond exploitation.

This provincial election must be a reckoning. Candidates should not be able to dodge the question: ‘Do you believe in fully funding our only public university and putting that funding in the hands of those who keep it alive?’

Neglect is a choice. Transformation is possible. And Juniper House shows us how.