The case for affordable housing

Whether you’re concerned with human rights or simply with dollars, investing in affordable housing makes sense

Housing is, in fact, a human right. Whether or not you care about human rights and dignity, though, there’s also a financial case to be made for ending homelessness.

Canadian studies have demonstrated that investing in solving homelessness by providing housing and necessary wraparound supports is net cheaper than the increased healthcare, policing, criminal justice system, and emergency shelter costs associated with choosing not to adequately fund long-term solutions. A 2020 study found that every dollar spent on supportive housing interventions for people experiencing homelessness saves $2.60 in public spending.

The status quo is not cost neutral, and this critical point is often left out of discussions around housing and homelessness.

Cost-savings analysis is, arguably, the most traditionally economic and least nuanced way to assess return on investment in social programs; it is, not coincidentally, a popular one in our neoliberal climate. Yet, despite more than a decade’s worth of clear evidence that not only are investments in housing sound from a social point of view, we continue to see a lack of investment to even maintain the housing supports that currently exist.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

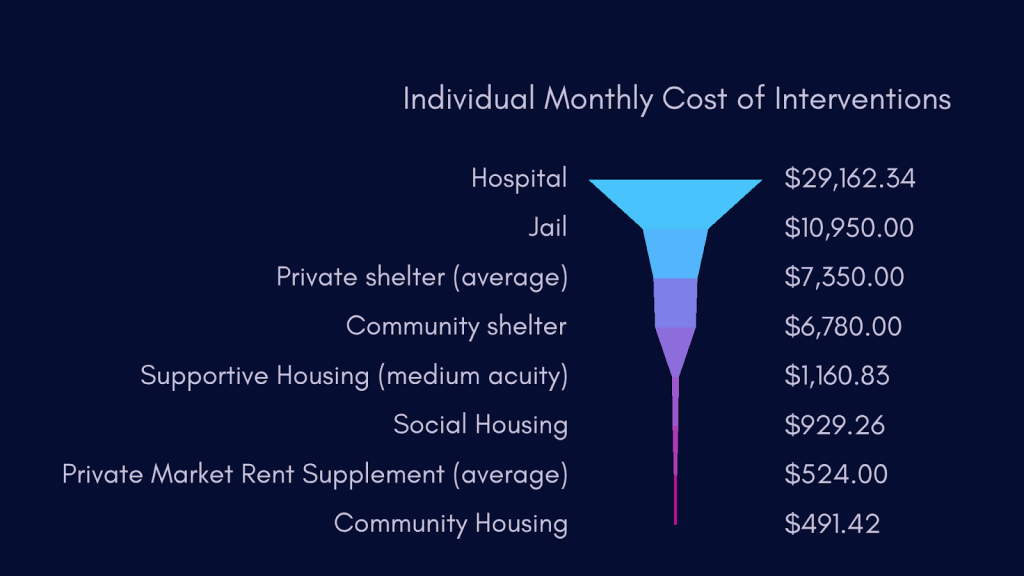

There’s a graph I’ve used in a few different presentations and reports over the years. Every time I bring it up, I have to give my head a shake and double-check my numbers, just to be sure.

The data, drawn from NL Housing, community housing providers, Quality of Care NL, and Statistics Canada, paints a clear picture: the consequences of not providing a structural, long-term solution to housing insecurity, and the temporary responses on which our systems currently rely as the default, are orders of magnitude more costly than assuring that safe, affordable housing is available to those who need it.

What the provincial parties are promising

Meanwhile, in an election where issues around ”public safety” have been front and centre, the emphasis has been on policing and incarceration. Little has been said by two of the province’s three major parties on the topic of investments in community, supportive, or public housing and the wraparound services that make transitions out of homelessness and housing insecurity more stable and viable in the long-term.

If we are truly concerned with the prudent spending of our tax dollars, we should expect programs which produce meaningful results: long-term social benefits, individual stability, and community well-being. As it stands, we are spending copious amounts of money to, at worst, punish those experiencing homelessness for doing so, and at best, prevent imminent death with no long-term benefits at the individual or collective level. This is socially and economically unsustainable. Yet many candidates and parties seem to be doubling down on the age-old, tried-and-failed approach of throwing police at the problem of poverty and expecting it to suddenly produce different results.

Thus far, the NDP has the most robust housing platform, including building 1,000 new homes annually. Their plan outlines the creation of a new provincially-owned corporation to finance this development, the details of which are presently unclear. Housing completions in the province sat at 654 in 2024; a 54 per cent increase in that figure from this initiative alone would need to address other regulatory and logistic barriers such as municipal approval processes and skilled-labour shortages in order to be viable.

The Progressive Conservative platform doesn’t appear to address housing directly; there is a single reference to support services in the “Safer Living” section of their website which says they will “focus on recovery by helping people get access to detox, treatment and sober living.” While expanded access to this specific type of support is needed (I wrote a report in 2024 in which many people with lived experience whom I interviewed emphasized the need for a diversity of support services, including those focused on sobriety), this exclusionary focus ignores the fact that other supports are likewise necessary.

The Liberal platform is likewise scant on specific attention to housing issues; an announcement on a renewed process to access crown land mentioned that it “will include Requests for Proposals for housing developments in high-demand areas.” This is welcome news, in particular since funding programs to acquire land and buildings aren’t currently available. Such an initiative could catalyze affordable housing projects if deployed thoughtfully, in particular if it prioritizes community and social housing development. These types of housing create long-term affordability through units which are not vulnerable to the pressures of the private market.

The past decade under a Liberal government has seen precious little in the way of developing these types of units, however. In 2023, the NL Housing Corporation issued an request for proposals for affordable housing units, valued in excess of $80 million. Ultimately, of the 922 units approved under the program—a paltry 130 units, or 14 per cent—were from non-profit organizations.

This is significant for a number of reasons. First, at a practical level, the request for proposals permitted the private sector to charge higher rents for units than the community sector and had a higher income threshold for tenant admissibility. So, investments in the community sector would have provided lower-cost housing to households in more dire need. By the same token, the private sector commitment to the affordability terms was set at 15-20 years. After these operating agreements expire, private landlords are free to do as they please with the units: sell them to realize the return on the investment of public money, or raise rents to whatever rate they please (rent control being, as it is, missing from our current tenancy legislation, something the NDP says it will change). Effectively, at the end of the day, taxpayer money to fund private-market units produces a solution for a period of time, which then is converted into private profit — to say nothing of the rental income garnered by the private sector in the interim. Conversely, investing in community housing creates perpetually affordable housing, a solution that lasts.

Investing in community and social housing pays off

A similar logic applies to considering the benefits of investing in community and social housing compared to private-market rent supplements. These supplements are intended to bridge the gap between household incomes and the cost of rent. NLHC spent $15.3 million on rental assistance in the 2023-24 fiscal year, more than double its expenditure on partner-managed (community) housing. While these rental supplements provide direct benefits to the individuals receiving them, they do nothing to change the circumstances in the housing market writ large; the problem is temporarily solved for that household, but the supply of affordable housing overall remains unchanged. In the absence of rent control, rent supplements amount to funneling public money through low-income people to the private sector to realize uncapped profits. This program also presumes the availability of rental units which, given the province’s 2.1 per cent vacancy rate in 2024, is far from a reliable assumption.

A report I authored earlier this year (which used methodology developed by Deloitte on the economic potential of community housing development) showed that raising Newfoundland and Labrador’s share of community housing from the current 0.3 per cent to the OECD average of 7 per cent of total housing stock could generate between $3.9 and $7.4 billion in economic activity, even when compared to investing in private-sector development. Not only are we leaving vulnerable people literally out in the cold by failing to develop more community and social housing — we are leaving money on the table, something we can ill afford to do in our present economic climate.

Housing is an essential building block of a healthy community and a good life. It is a human right and a necessary condition for living with dignity and safety. We should never be forced to make economic arguments for these basic necessities. Nevertheless, those economic arguments are strong, sound, and backed by research. There is no excuse for doubling down on criminalizing poverty and homelessness instead of choosing to meaningfully address these issues with housing and support services. We, as taxpayers, and as humans, deserve better.