Why I pressed Trudeau on genocide

Our silence empowers the status quo, which in this case means upholding Canada’s complicity in the continued massacre of Palestinians

Like many journalists, I have a love-hate relationship with my profession. After graduating from J-school in 2003, I moved halfway across the country to take my first job as a newspaper reporter, only to leave months later feeling unfulfilled and wondering if journalism was for me.

Eventually, I returned to school and dabbled in the social sciences at Memorial University, hoping a more informed outlook on society and the world might bring me closer to finding purpose in news reporting.

As part of my education I also joined advocacy groups, where I found others who, like me, recognized deep injustice in various issues, and in the general state of the world.

Education in genocide

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

In high school we were taught about the Holocaust, and how after World War II the United Nations adopted the Genocide Convention, an unprecedented international treaty that gave a name and definition to the horrific act of genocide as specific crimes “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.”

With the global consensus that genocide is a violation of international law came the promise of “never again”. Yet, in 1994, while All-4-One’s song I Swear was topping the Billboard charts and grunge bands like Soundgarden, Nirvana and Pearl Jam were taking the rock world by storm, more than half a million human beings in Rwanda were slaughtered over a three-month period.

“Never again” was a broken promise. Among the reasons for the international community’s collective failure to stop the systematic slaughter of Tutsis was the fact that the victims were Black, and African — less than human in much of the world’s eyes.

It was just a year or so after the Rwanda genocide when I learned what had happened. Fifteen-year-old me couldn’t believe this was possible. That human beings are still capable of such atrocious acts. That it just happened. And that thousands of people were being murdered with guns and machetes every day at the exact same time I was getting up, eating cereal, going to school, and coming home to play video games. Most frighteningly? The genocide happened while the world watched.

That’s why, in 2007, I started a Memorial University chapter of STAND Canada, a student-led anti-genocide group that lobbied the Canadian government to use diplomacy and peacekeeping to end the violence in Darfur. If genocide isn’t worth standing against, I thought to myself, what is?

Today, many accuse those critical of Israel’s occupation of Palestine as being uninformed or misled about the nature of the conflict. They say those sympathetic to Palestinians, some 40,000 of whom have been killed since October 2023, should be quiet. During my time advocating for intervention in Darfur, I faced similar criticisms.

It’s true that most Canadians don’t know the history of the Middle East, or understand the nature and evolution of the Israel-Palestine conflict. It also holds that well-intentioned people can push their governments toward policies that do more harm than good — including interventions in conflict and war.

But these arguments cannot and must not distract from the resounding demand from people and nations across the world for an immediate ceasefire in Palestine and an investigation into Israel’s actions, which many believe amount to genocide. In response to South Africa’s case against Israel, which in December 2023 accused Israel of genocide, the International Court of Justice issued an interim judgement in January which acknowledged that at least some of Israel’s actions outlined in South Africa’s complaint, if proven, could fall under the Genocide Convention.

Holocaust and genocide scholars have disagreed on whether or not Israel’s actions in Gaza constitute genocide. But there’s a “near-consensus in the field that genocides are almost invariably perpetrated by states,” Abdelwahab El-Affendi, a professor of politics at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, wrote in February 2024. “A garrison state like Israel could not be threatened by an impoverished and besieged enclave like Gaza. By contrast, the genocidal intent and consequences of the Israeli assault are becoming indisputable by the day.”

El-Affendi questions whether the discipline of genocide studies is futile, given its failure to live up to its aim of preventing genocide. “The minimum the field could do is to question the narratives of the perpetrators and those cheering them on,” he writes, adding that “if a series of actions approach genocide sufficiently to occasion a debate on whether they are genocide or not, then they are evil enough to be denounced without ifs or buts; even more so if the aim is to sustain an unjust system.”

Whether the International Court of Justice ultimately decides that Israel’s actions constitute genocide, tens of thousands of innocent civilians, many of them children, are being slaughtered. Again. While the world watches.

Why genocide is personal

In 2008, I traveled to Sudan with two other anti-genocide advocates to interview people fleeing the violence in Darfur. We would deliver their stories and messages straight to Canadians — not just politicians, but to university students and others across the country. We flew to Nairobi first, where we met Liberal MP Glen Pearson, a career firefighter from London, Ont. who, along with his wife Jane, founded the non-profit Canadian Aid for South Sudan. We were also joined by Liberal MP and former Health Minister Carolyn Bennett, who at the time was the Official Opposition’s Health Critic. From Nairobi we flew to South Sudan.

The Liberal Party of Canada seemed open to making Darfur a policy issue. Plus, just weeks before our trip, Michael Ignatieff was elected as the party’s new leader. An academic, Ignatieff was a leading figure in the creation of the new Responsibility to Protect doctrine, which inspired hope that Canada’s potential next prime minister would make Darfur, and our country’s response to the crisis, a priority in the House of Commons.

I am about to describe extreme violence and suffering. Please read with care.

Once we arrived in South Sudan (which two years later gained independence and became its own sovereign state) near the Darfur border, my colleagues and I hitched rides with United Nations staff who were traveling by ground in the region. We spent several days in IDP (Internally Displaced Persons) camps — small communities of people living under tarps and tents, largely without food or clean water, many of them starving, and all of them traumatized.

I sat with people — sometimes entire families, or what was left of them — listening to first-hand accounts of the violence. Among them was a woman who agreed to speak with me through an interpreter. We sat together in the dirt outside her tent while she nursed her baby. I will never forget the look on her face as we spoke. I’d never seen such emptiness, such profound nothingness in a person’s eyes. She was staring into a void that I couldn’t see.

The mother, who was around 30, told me that just days earlier armed militiamen in trucks stormed her village. They pillaged and razed homes, rounded up and castrated men, raped women, and abducted children (likely into slavery and/or to train as child soldiers). Hiding with her baby in her arms, she watched in horror as they took her children at gunpoint. Her husband, she told me, also had no choice but to hide if he wanted to live. Over the next week, she traveled on foot with others from her village to find refuge in the South. They only moved at nighttime, when they were less likely to be seen. During the days, they hid in bushes, waiting for nightfall so they could move again. She carried her baby the entire way.

Eventually, she found the encampment, where she was reunited with her husband. When she and I met, he was out foraging for groundnuts and the scarce piece of wood which would allow them to light a fire and boil water. The UN’s World Food Program was feeding people in the area but had pulled out to distribute food in places with more pressing needs. People were left to fend for themselves. They chipped the bark off trees and boiled it for food.

At one point, someone handed me their baby, a lethargic one-year-old whose eyes were filled with tears. He may have been on death’s doorstep, but there was nothing anyone could do. No food. No water. No doctors. No medicine. I told the family I would return to Canada with the urgent message that survivors from Darfur need help.

But when I returned home, something happened. My stories to those whom I expected would feel the same concern and urgency as I did, didn’t resonate like I hoped. Most didn’t know anything about Sudan, feel any desire to learn about the genocide, or believe it was their responsibility to — well, protect. As more and more of my conversations proved fruitless, and without appreciating in real time the impact the experience was having on me, I fell into deep despair and was paralyzed with hopelessness… and guilt.

Just like Rwanda, the world had forgotten its promise of “never again,” I thought. And there was nothing I could do to change that, or to protect those in Sudan whose hopes I had raised when I gathered their stories.

There’s no neutrality

The violence in Sudan continues today, one of many places in the world where everyday people like you and me are subject to unspeakable violence. Like Israel’s occupation of Palestine, all conflicts are layered with complexity and nuance. But no level of intricacy warrants violence like Israel’s continued massacre of Palestinian civilians in Gaza and the West Bank today.

That’s why, when I learned last Wednesday that Trudeau would be speaking at a school food program announcement in my neck of the woods, I had to press him on Canada’s complicity in—and his government’s response to—a possible genocide.

For months, the Liberals have downplayed Canada’s role in supplying Israel with weapons and military goods likely being used in its war on Palestine. Over the past decade we’ve sold Israel more weapons and equipment exports than ever before, totalling $26 million in 2021, and $21 million in 2022. During the first two months of Israel’s war on Gaza, Canada authorized at least $28.5 million in new military export permits for Israel.

Despite the Liberals’ support behind a non-binding motion passed in the House of Commons last March that Canada will halt future arms shipments to Israel, we learned last month that Canadian companies could export $95 million more in military goods to Israel by the end of 2025 as a result of permits that were previously approved by the federal government.

We also learned in August that Canadian weapons are also making their way to Israel via the United States. We don’t know the extent to which Canadian-made goods are being used to kill Palestinians; our government won’t tell us.

A growing number of Canadians are demanding that the government impose a full arms embargo and cut diplomatic ties with Israel.

With genocide, or anything close to genocide, there is no neutrality. We try to stop it, or we don’t.

Our silence empowers the status quo, which in this case means upholding Canada’s complicity in the continued massacre of Palestinians. Our voices, in great enough numbers, could compel one of Israel’s closest allies to exert pressure on the Benjamin Netanyahu regime, which would signal to the rest of the world that Israel is losing the support of even its staunchest political allies.

Trudeau’s eyebrow-raising responses

I was one of the last reporters to put my questions to Trudeau last Wednesday. Others asked him about the National School Food Program, or the NDP’s withdrawal from its confidence-and-supply agreement. When it was my turn, I asked the prime minister why Canada is remaining complicit in Israel’s war on Gaza and why he isn’t doing more to end the violence.

“Since December, we have been calling for a ceasefire. We need to see an end to the violence, we need to see a return of the hostages. We need to see Hamas lay down its arms and stop using Palestinian children and civilians as shields,” he said, repeating one of his old talking points. “We need to see the Israeli government abide by international law and rules. And we need an immediate ceasefire. We need to get back on that path towards a two-state solution where a peaceful, secure Israel lives alongside a peaceful, secure Palestinian state. That is the work that Canada has been doing on the world stage for many months. That is what we are going to continue to do — to push for that two-state solution.”

That same morning, CBC reported an account of Israel’s military using Palestinians as human shields. In fact, Israel has a known history of using Palestinians, including children, as human shields. By accusing Hamas of war crimes, while neglecting to criticize Israel for attacking hospitals, bombing schools and refugee camps, and for issuing evacuation orders to Palestinians only to then attack those supposed ‘safe zones’, Trudeau’s remarks misrepresent what is actually happening in Gaza. Instead, they represent a lackluster attempt to justify Canada’s complicity.

For my second question (the PMO imposed a two-question rule), I asked Trudeau to answer the calls coming from many Canadians: why isn’t he unequivocally condemning Israel, cutting diplomatic ties, and ensuring that Canadian goods aren’t being used to kill Palestinians? (I referenced the recent revelations that the U.S. approved the sale of approximately $61.1 million in weapons to Israel, with Quebec arms manufacture General Dynamics Ordnance and Tactical Systems as the deal’s “main contractor.”)

“Israel has a right to defend itself in accordance with international law,” Trudeau replied, adding Canada has called for “Hamas to lay down its arms,” and for Israel “to abide by international law.”

Last November, United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on the Occupied Palestinian Territories Francesca Albanese said Israel cannot claim the right of self-defense under international law because it is occupying Gaza. Others argue that if Israel did have a right to self-defense, that right would not support its disproportionate response and its targeting of civilians. Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack killed around 1,200 people, while Israel’s war on Gaza has killed upward of 40,000. Some estimate that the scale of devastation of Gaza will lead to 186,000 or more indirect deaths in the years to come.

Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East called Trudeau’s responses to my questions “lies,” saying he “regurgitated false Zionist talking points and failed to acknowledge Canada’s complicity in Israel’s genocide in Gaza.”

Asking Israel to “abide by international law” when it already has a credible claim of genocide against it, and failing to stop the flow of Canadian-manufactured goods likely being used to kill Palestinians, is not the kind of leadership many Canadians want from a prime minister. With Trudeau’s Liberal empire crumbling around him amid calls for his resignation as the party’s leader, it’s curious that after all this time his talking points haven’t changed, and that he’s not taking a stronger stance on Israel.

Concluding his response to me, Trudeau alluded to recent hate-motivated incidents and crimes in Canada (presumably anti-semitic ones). “This is an incredibly difficult situation that has tangible repercussions on millions of Canadians who are worried about the rise in hatred here at home, who are worried about sending their kids to school as a new school year starts in universities and high schools across the country,” he said. “We need to remember who we are as Canadians, which is fighting for our values of peace, openness and understanding, putting aside the hate and being committed to a peaceful future in the Middle East where a secure Israel lives alongside a secure and internationally-recognized Palestinian state.”

Canada has laws that make hate crimes illegal. Every act of racism or discrimination must be addressed with the seriousness and urgency it deserves. Those who genuinely care about universal human rights, however, might suspect that Trudeau’s deflections are intended to once again downplay Israel’s actions and Canada’s complicity in them.

Breaking the 2-question rule

Unsatisfied with Trudeau’s response, I pressed some more. “It sounds like you’re downplaying the significance of genocide, or what could very well be genocide,” I said, looking at him. He nodded and gestured, indicating to me that his response was over. “You don’t want to talk to, speak to the genocide piece?” I asked. “You got two questions,” he said. “There’s a whole bunch of other journalists — I look forward to hearing from them as well.”

There weren’t a “whole bunch of other journalists” waiting to ask questions. There were two. Trudeau’s display of disingenuousness aside, his remark was irrelevant. The prime minister sets the two-question rule, and the prime minister can be flexible with the two-question rule, especially when asked to clarify his position on his country’s complicity in genocide.

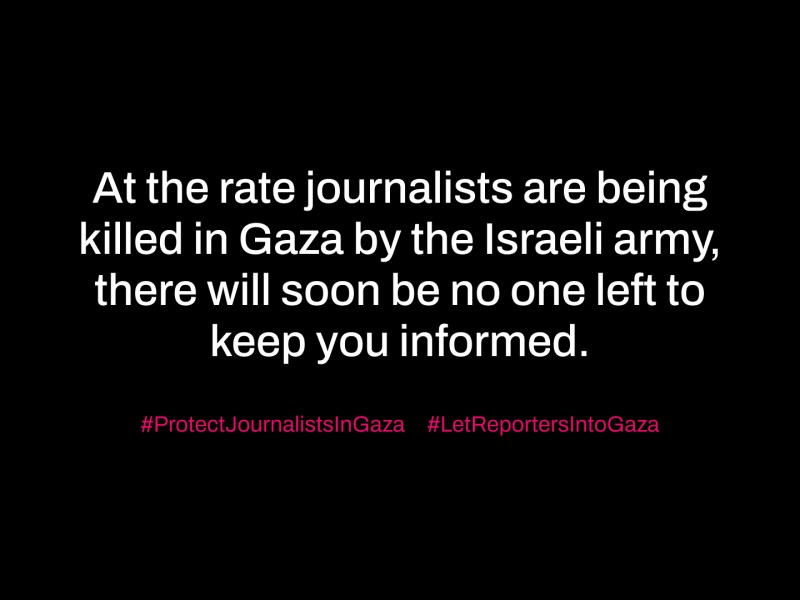

More to the point on Israel and Palestine, journalists have special access to Trudeau and other policy-makers that other Canadians don’t. It’s our civic duty and our democratic responsibility to hold politicians to account, especially on acute and urgent matters.

History may not look kindly on the Trudeau government’s tepid response to Israel’s war on Gaza, especially if the ICJ sides with South Africa in its claim of genocide.

Similarly, I wonder how Canadians might look back on us as the ones who brought such a government to power but refused to hold it to account when it armed a state in the midst of a killing spree.

This article was originally published Sept. 8, 2024 in Indygestion, The Independent’s free weekly newsletter. Sign up below.