Why taxpayer subsidies for Big Oil won’t create more jobs

As Equinor delays Bay du Nord decision, report finds less than 1% of Canada’s jobs now in fossil fuels

With the US attacking Venezuela, seizing oil tankers, and threatening to invade Greenland, it’s no wonder the price of Brent Crude fell below $60 a barrel earlier this month.

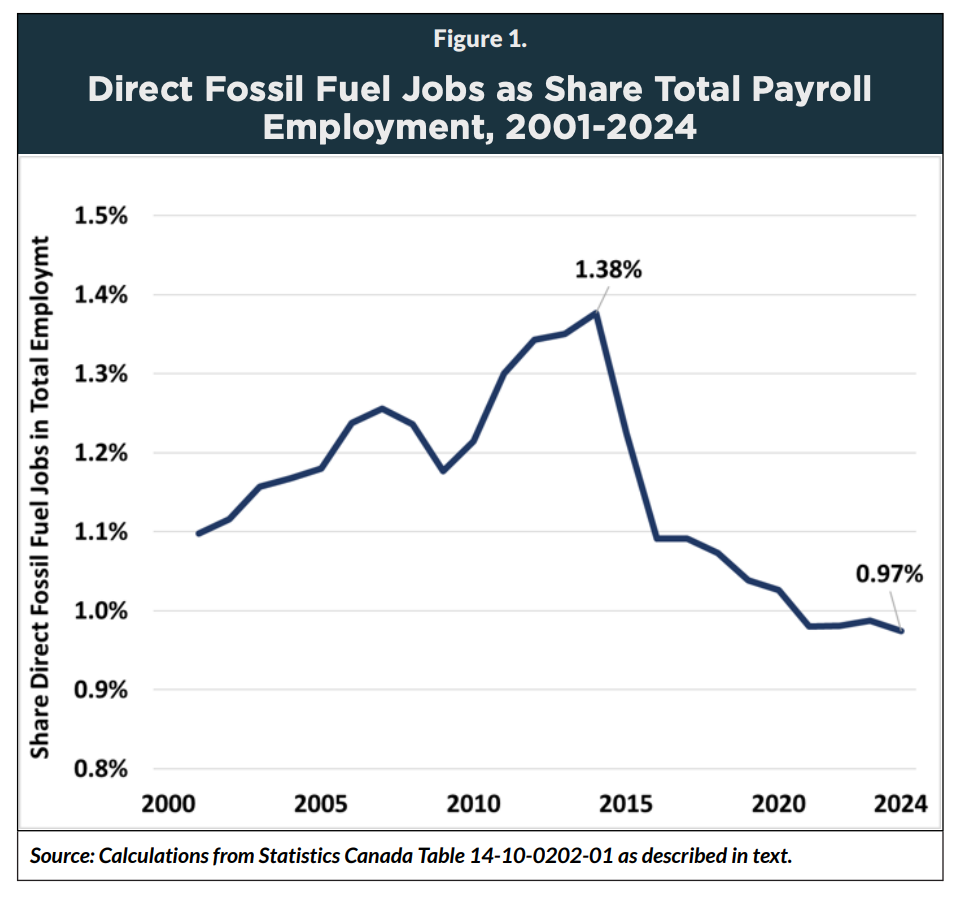

The number of oil jobs and their once-high salaries are also on shaky ground, according to a new report from the The Centre for Future Work, which claims less than 1 per cent of jobs in Canada are ‘oil jobs’ — and that number is declining.

This downward trend should make governments think twice about calls for taxpayer subsidies, such as the recent request from TradesNL for the province to “sweeten the pot” (as CBC put it) by subsidizing or offering tax credits to Norwegian energy giant Equinor so that Bay du Nord would be more economically attractive.

On Monday, business news site allNewfoundlandLabrador reported that Equinor pushed back its December 2025 deadline to make a final decision on the offshore oil megaproject, which environmental and Indigenous groups have said cannot proceed if the province and Canada hope to meet their climate targets.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

What do subsidies have to do with oil jobs?

The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) found that Newfoundland and Labrador subsidized fossil fuel companies to the tune of $82 million in 2020-2021 and even more the following year.

Economist Jim Stanford and labour researcher Kathy Bennett are behind the Centre for Future Work’s new report, Transition Away from Fossil Fuel Jobs is Already Occuring: Here’s how to Manage it Better, which challenges the logic of subsidizing oil companies to ‘create’ jobs. It also addresses hype around employment numbers in the fossil fuel industry and maps some of the many future paths available to former oil workers.

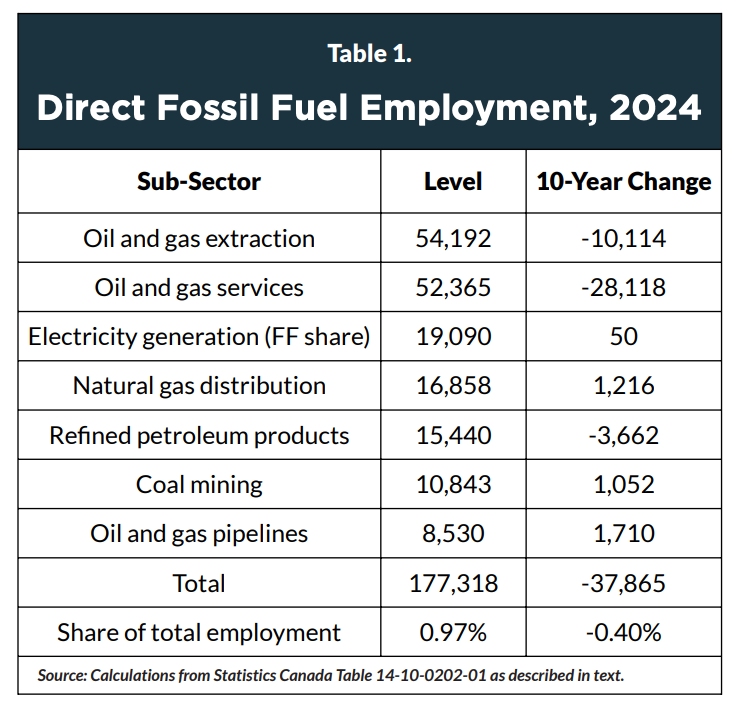

The report estimates there’s currently 177,000 (direct payroll) fossil fuel jobs in all of Canada. Their research is backed up by many other sources that may have slightly different, but relatvively low, numbers sharing the conclusion that direct fossil fuel employment (and petroleum-related employment, in particular) represents a small (around 1 per cent) and shrinking share of total employment in Canada.

The authors also challenge a claim from industry lobby group Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), which has suggested “every direct oil and gas job creates two indirect jobs in businesses that sell to oil and gas producers, and three induced jobs, where oil and gas workers spend their money.” Under these assumptions, CAPP estimates there are upward of 900,000 oil (and spinoff) jobs in Canada. But that estimate, Stanford and Bennett say, is “based on the application of a simplistic (and unbelievable) 6-to-1 employment multiplier to reflect indirect and induced jobs related to petroleum production.”

The authors explain their estimate of 177,000 jobs includes jobs in oil and gas, coal, petroleum refining, pipelines, and natural gas distribution. They say that even the share of electricity generation tied to fossil fuel combustion is shrinking, and that 38,000 jobs in the sector have disappeared since 2014.

As an example of local impacts, last fall Exxon Mobil announced plans to cut 20 per cent of its Canadian workforce, including jobs in Newfoundland and Labrador.

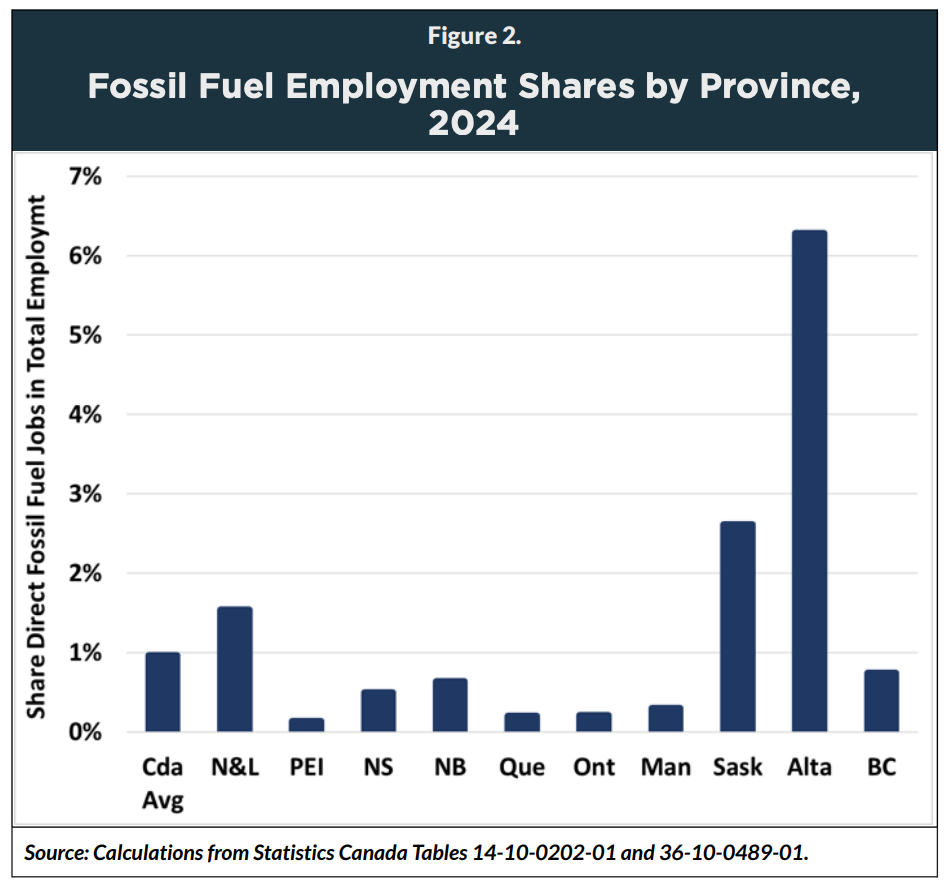

The report says oil workers represent around 1.5 per cent of Newfoundland and Labrador’s workforce, slightly higher than the national average. The percentage of oil and gas workers in this province is certainly higher though, since the authors base their numbers on the location of jobs, not the province workers are from, which means Newfoundland and Labrador workers who fly in and out of the oilsands are included in Alberta’s numbers.

Fossil fuel worker salaries are also on a downward trend, the report says. Typically between $2,500 and $3,000 weekly, Stanford and Bennett found wage gains for oil workers lagged behind inflation over the past decade, resulting in “a substantial decline in real weekly incomes — which fell by 14% in both sectors.” They also argue that decline “came at a time when real earnings grew by almost 5 per cent in the overall labour market and while oil companies posted massive profits.”

Production booms while jobs fall

The decline in oil jobs has happened against the backdrop of massive increases in fossil fuel production. In 2024, oil and gas production in Canada “hit a record 8.4 million barrels of oil equivalent per day, up from under 6 million in the early 2010s,” the report says.

Stanford and Bennett say the decline in oil jobs is a result of decisions made in oil company boardrooms, not climate change policies. Oil companies are simply not investing in other projects, indicating they’re planning for demand to taper even further. Instead, they’re passing along profits to shareholders.

Canada’s big four oil companies—Cenovus, Imperial, Canadian Natural Resources, and Suncor—are 60 per cent American-owned, according to Canadians for Tax Fairness, which points out the majority of the companies’ dividends and profits leave Canada, having “paid out over $58 billion of profits to foreign owners through dividends and stock buybacks from 2021-2024.”

While raking in profits, the report details how the industry is scaling down its workforce through attrition, automation, off-shoring, shifting production to the US, and via mergers and acquisitions. For example, Cenovus’ 2021 purchase of Husky Energy led to two rounds of significant job losses. The Centre for Future Work’s report also describes how oilsands companies are quietly replacing retiring truck drivers with automated trucks, and how around 58 per cent of Canada’s fossil fuel workers will retire by 2050.

No straight line from oil to renewable jobs

Part two of the report examines oil and gas workers’ attitudes around the shift to renewables. Almost 60 per cent of workers surveyed agree climate change is caused by humans and fossil fuels need to be phased out.

Stanford and Bennett say the transition to renewable energy “will have a net positive impact on employment,” since those energy systems are “more labour-intensive than most fossil fuel activities (which support very few jobs per unit of output due to very capital-intensive production techniques).”

Like many before it, the report identifies options for transitioning oil workers who may choose to work in “nonfossil resources, construction, manufacturing, and transportation” because those positions employ similar skills and working conditions.

While there are many options available for workers transitioning out of the fossil fuel sector, some surveyed said they worry about lower salaries in other industries.

Can N.L. avoid another moratorium-like shock?

The Newfoundland and Labrador Federation of Labour (NLFL) is planning a conference this spring to discuss a transition-from-oil roadmap to support workers. NLFL President Jessica McCormack has said the province’s failure to prepare for major job market change is what led to much of the social and economic devastation of the cod moratorium. “Now that we can see this decline in oil industry jobs, we need to prepare,” she said.

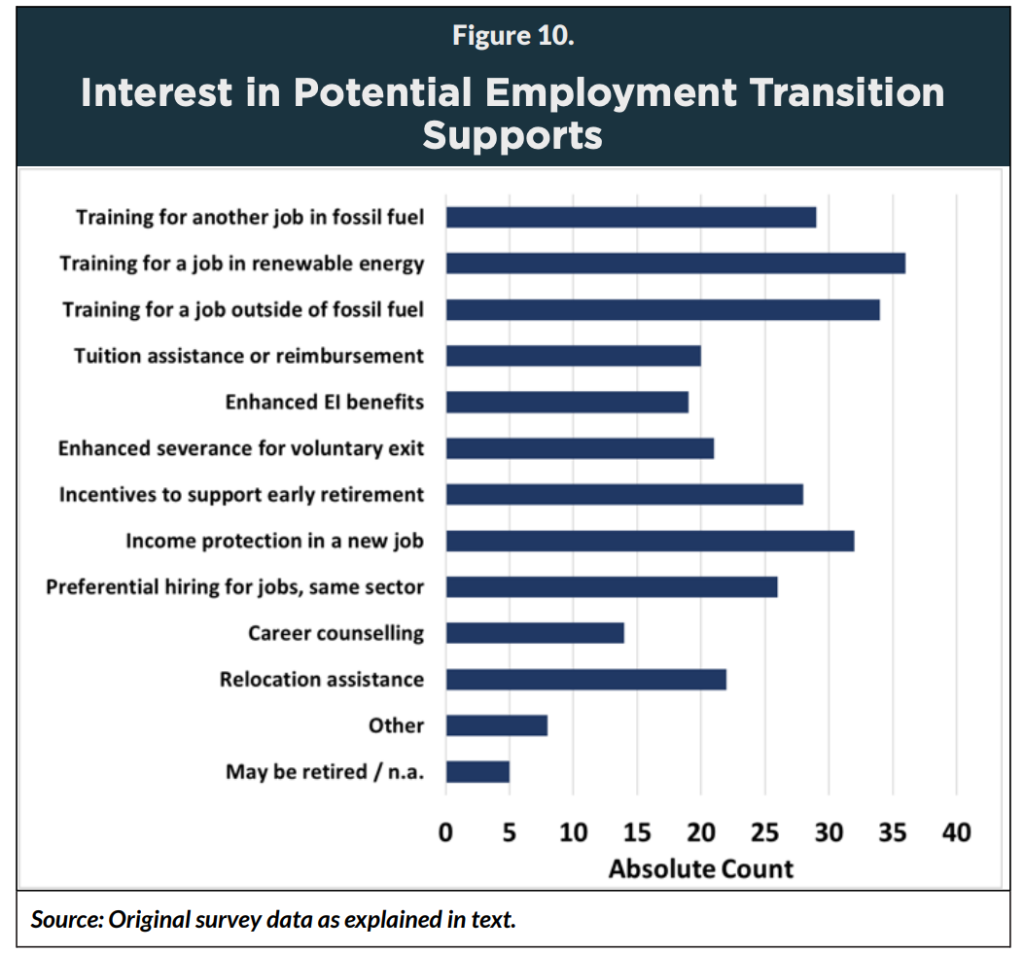

The report calls on provincial and federal governments to empower workers, implement transition planning that reflects the labour market changes, and allows for pension bridging and transition training with early access to health benefits. Workers surveyed mentioned the need for: “relocation assistance, early retirement incentives, preferential hiring for other jobs within the current industry, enhanced employment insurance protection, and tuition assistance.”

Instead of throwing taxpayer subsidies at an incredibly profitable oil company like Equinor—whose gross profits for the 12 months ending Sept. 30, 2025 was $53.8 billion—surely using that money to help workers transition to job market realities is a far better use of public money.

Read or download the Centre for Future Work’s full report: