N.L. parties agree we need more say on fisheries — but what about climate change?

What three party leaders said about provincial fisheries and ocean priorities—and what they didn’t say

With fisheries and oceans under federal jurisdiction but critical to Newfoundland and Labrador’s economy and identity, Seasplainer asked Liberal Leader John Hogan, NDP Leader Jim Dinn, and PC Leader Tony Wakeham how they would advocate for the province and what tools they would use to support coastal communities.

What emerged from their responses (available in their own words here) were areas of consensus—and some notable departures and gaps.

All three parties agree the province needs a stronger voice with Ottawa and that sustainability must balance environmental protection with fisheries livelihoods. But they diverge sharply on approach: the NDP prioritizes research and data, the PCs name specific policy battles like increasing fisheries markets, including for seal, and opposition to the proposed marine protected area on the south coast, while the Liberals emphasize pressing ahead on their current advocacy with the federal government.

Meanwhile, no leader spoke to climate change and Canada’s role in international ocean governance—despite mounting global urgency.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

Where parties agree

Equal partnership with Ottawa

All three parties emphasized that the province must be an equal partner in fisheries decision-making. The NDP and Liberals framed this as collaborative advocacy, with NDP Leader Jim Dinn saying the province must be “a loud and vocal defender of the interests of our fisheries” and act as “a united front with workers.” Liberal Leader John Hogan noted his government has been working toward this goal, stating “Our province should have a direct say in decisions that affect our resources.”

PC Leader Tony Wakeham took a more confrontational approach, declaring that “Our fishery is too important to the people of Newfoundland and Labrador to be dictated by Ottawa alone” and promising to “appoint a full-time Fisheries and Aquaculture Minister to stand up for our province and push for joint management.”

Balancing sustainability with livelihoods

All parties acknowledged the need for approaches that balance environmental conservation with fisheries. Dinn emphasized “striking a sustainable approach that works for fish harvesters while protecting the environment” to ensure resources “may be enjoyed by generations to come.” Wakeham committed to “a strong regulatory framework that balances environmental protection with sustainable growth.” And Hogan identified “ensuring that our fishery, oceans and coastal communities are sustainable,” as a priority.

Consulting citizens and working directly with fishers

Both the NDP and Liberal leaders emphasized a need for ongoing public consultation. Dinn pledged to “consult thoroughly with those people, communities, and industries affected and incorporate their interests and concerns as much as possible into any decision.” Hogan similarly committed to “engagement and consultation with industry stakeholders.”

Meanwhile, the NDP and PCs both emphasized working closely with those in the industry. Dinn spoke of being “a voice for the fish harvesters and plant workers on the ground, and for local organizations and groups.” Wakeham promised to “work in partnership with harvesters and processors, and never make policy changes without ensuring they grow—not hinder—the industry.”

Where the parties diverge

Only the NDP identified research as a priority area for provincial advocacy. Dinn argued that “the best results only come from the best decisions, and these can only be made by using plenty of good data,” promising to advocate for “more and better research in fish stocks and the environment offshore” and partner with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) on these efforts.

The PCs were the only party to name concrete issues they would address, including advocating for “a fair food fishery for our province, and greater access to new markets, including for seal products.” Wakeham also took a stand on aquaculture, vowing to “stand against federal overreach, including the proposed marine protected area on the South Coast, which threatens the future of local aquaculture and coastal communities.”

Why this election matters for ocean policy

The timing of this election comes at a critical juncture for ocean policy. The decisions the next provincial government makes about how to engage with Ottawa could have profound implications—not just for Newfoundland and Labrador’s fishing communities, but for the credibility of Canadian fisheries and ocean management on the international stage.

A planet under pressure

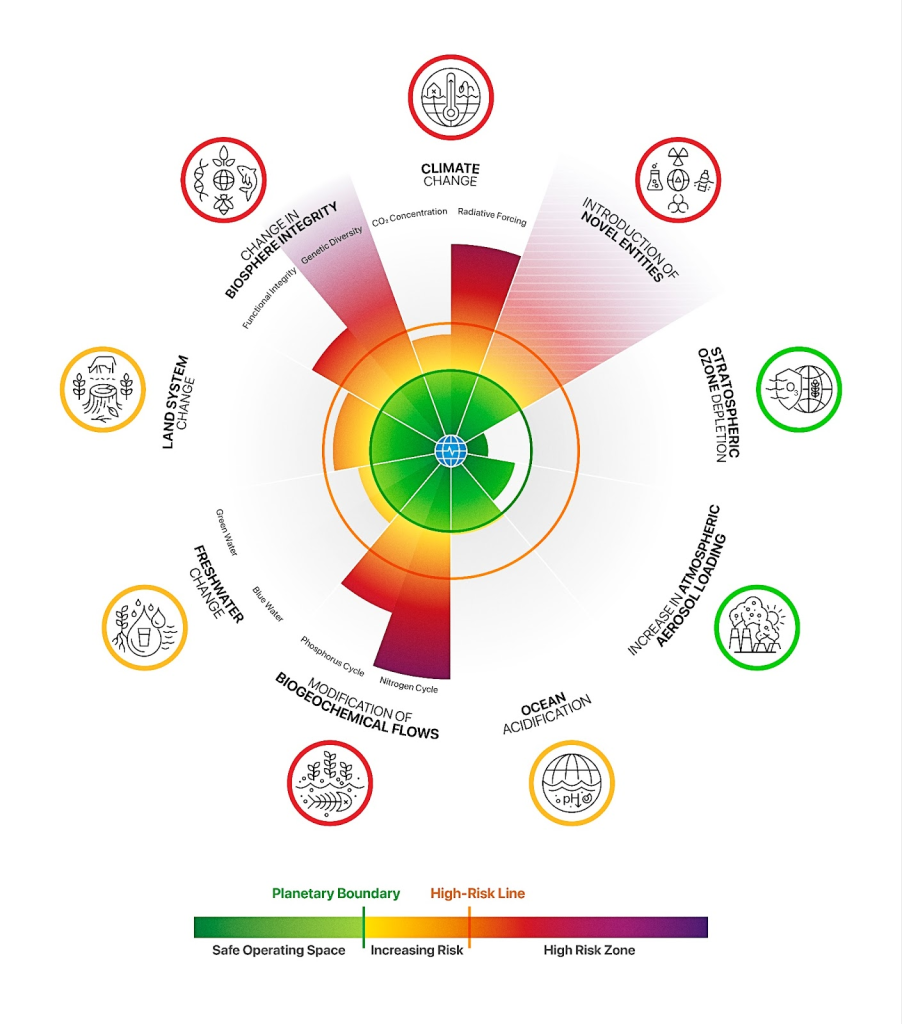

In late September, the Planetary Boundaries Science Lab at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research released findings showing that seven of nine critical Earth system boundaries have now been breached—one more than last year. The newest transgression: ocean acidification.

Since the industrial era began, the ocean’s surface acidity has increased by 30-40 per cent —pushing marine ecosystems beyond safe limits. Arctic marine life and cold-water corals, along with tropical coral reefs, are especially at risk. The decline of these ecosystems affect entire food chains, with consequences for fisheries and ultimately for people.

“The ocean is becoming more acidic, oxygen levels are dropping, and marine heatwaves are increasing,” Levke Caesar, co-lead of the Planetary Boundaries Science Lab, said last month. “This intensifying acidification stems primarily from fossil fuel emissions, and together with warming and deoxygenation affects everything from coastal fisheries to the open ocean. The consequences ripple outward impacting food security, global climate stability, and human wellbeing.”

Sylvia Earle, renowned oceanographer, put it starkly: “The Ocean is our planet’s life-support system. Without healthy seas, there is no healthy planet. For billions of years, the ocean has been Earth’s great stabiliser: generating oxygen, shaping climate, and supporting the diversity of life. Today, acidification is a flashing red warning light on the dashboard of Earth’s stability. Ignore it, and we risk collapsing the very foundation of our living world.”

This global context makes the provincial response in Newfoundland and Labrador all the more significant. The decisions our next government makes about fisheries science, federal advocacy, and coastal protection will play out against a backdrop of accelerating ocean change.

Northern cod: A case study in federal decision-making

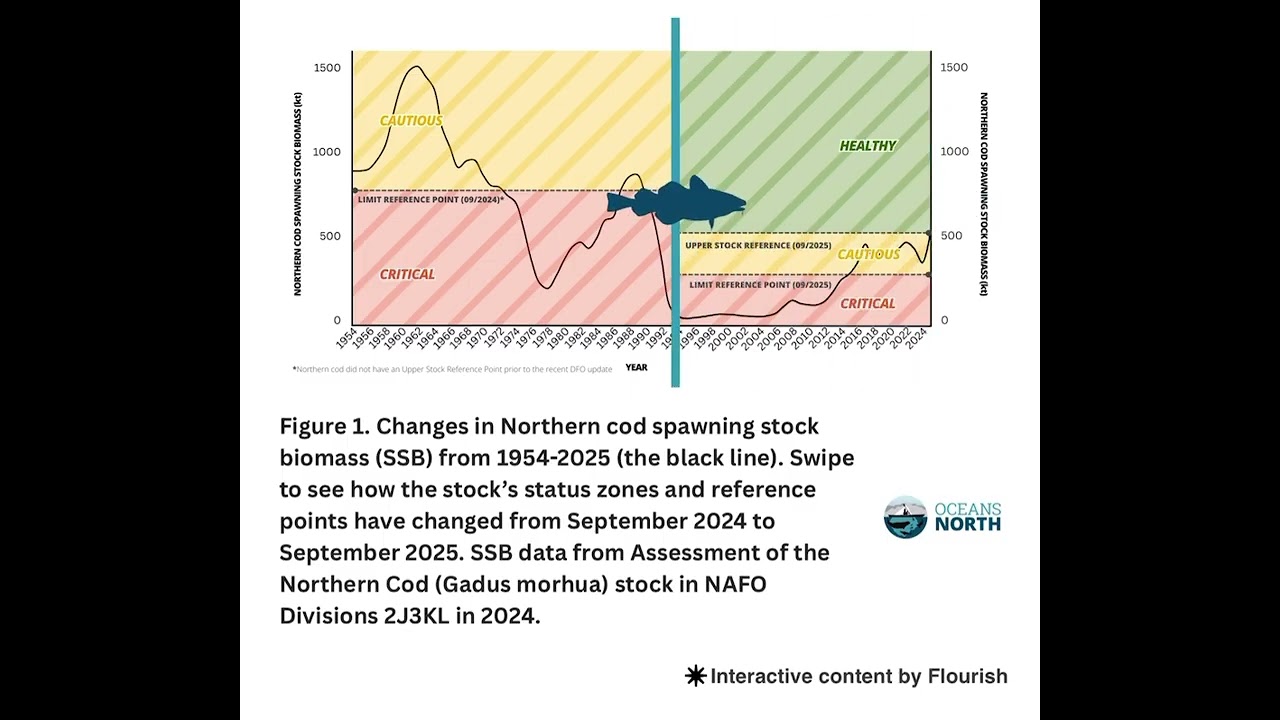

In early September, just before the provincial election campaign began, Fisheries and Oceans Canada quietly redefined what constitutes a “healthy” Northern cod stock—lowering the threshold by 270 kilotonnes and instantly moving the population from the “cautious” zone to the “healthy” zone. Independent scientists called it “goalpost shifting,” noting the stock hasn’t grown in a decade and remains a fraction of pre-collapse biomass.

The regulatory change aligned with intense industry lobbying to triple catch levels and capitalize on European supply gaps as Barents Sea and Icelandic cod stocks decline. Major UK retailers like Marks & Spencer—with rigid sustainability standards—are turning to Canada for certified cod to fill their freezer cases with fishcakes and fishsticks.

This is precisely the kind of federal decision-making that provincial leaders say they want more influence over. Whether the next government takes the NDP’s approach of advocating for better research, the PC’s confrontational stance against “federal overreach,” or the Liberals’ continued high-level negotiations could determine whether similar decisions are made with or without meaningful provincial and stakeholder input.

International commitments in limbo

Globally, Canada faces mounting pressure on ocean policy. The High Seas Treaty was ratified on Sept. 19, becoming legally binding with 60 countries—but Canada, despite having the world’s longest coastline, was not among them. When Jenn Thornhill Verma spoke with DFO officials at the UN Ocean Conference in Nice this summer, they said ratification was not a matter of if but when.

But months later, with the Prime Minister past the 100-day mark and no ratification in sight, ocean advocates are calling on Ottawa to take action. If Canada doesn’t ratify before the treaty enters into force in 120 days (by mid-January), it will miss its seat at the table for crucial discussions, for example, about creating marine sanctuaries.

Federal policies on hold

Domestically, key policies remain delayed. DFO has yet to release its whale-safe gear strategy or federal action plan on ocean noise—both years in the making and originally promised for spring 2025. It’s possible the department is waiting to see what the Nov. 4 federal budget holds before committing to timelines.

The government also eliminated the dedicated Minister of Fisheries and Oceans position, replacing it with a Minister of Fisheries—a change ocean advocates quietly noted but, given other pressing issues facing the new government, initially let slide.

Why provincial leadership matters now

With federal ocean policy in flux—from controversial stock assessments to delayed conservation strategies—the province’s voice has never been more important. As DFO Deputy Minister Annette Gibbons said at the UN Ocean Conference in June 2025: “The health of the ocean is critical to life on earth.” She cited climate change, overfishing, pollution, and biodiversity loss as examples of converging into a “global emergency,” adding that Canada has “placed the ocean at the heart of the solutions.”

But what went unsaid in Canada’s remarks during the conference was equally telling. Despite having a moratorium on deep-sea mining, Canada didn’t mention it. Similarly, while Canada’s marine protected areas standards ban bottom trawling offshore, the country remained silent on the practice.

These are the kinds of nuanced decisions where provincial advocacy—whether through research partnerships, dedicated ministerial attention, or strategic federal negotiations—could make a tangible difference in protecting both the ocean and the communities that depend on it, in a way that reflects what Newfoundlanders and Labradorians expect.

What priorities would you like to see the next provincial government pursue for the ocean and fisheries? Share your thoughts with us at seasplainer@theindependent.ca.