N.L. education system struggling to meet the needs of newcomer students

Families and organizations are working to create safe spaces for refugee youth to thrive, stay connected with their roots and build strong community connections

Eighteen-year-old Shrabontee Deepanwita arrived in St. John’s from Bangladesh, excited to start her undergraduate studies in behavioural neuroscience at Memorial University.

Unlike most new international students, Deepanwita didn’t spend the days before classes exploring the city and stocking up on her favourite foods. Instead, she spent two weeks trapped in a dorm. “I couldn’t see the weather, I couldn’t see any people,” she recalls.

Deepanwita came to St. John’s in August 2021, when pandemic quarantine measures were in place. She says the student residence team provided her meals and regularly tested her for COVID-19, but she wishes they had been just as attentive to her mental health. “It was a change of an entire continent, from Asia to North America.”

She admits she hadn’t fully anticipated how the geographical and cultural changes would impact her mental health, but says the university should be more proactive in offering mental health check-ins for international students adjusting to life away from their families, adapting to a new language, and navigating unfamiliar education, healthcare, and transportation systems. “There weren’t any resources where they were like, ‘how do you feel today?’”

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

Post-secondary education

Ken Fowler, director of the Student Wellness and Counselling Centre (SWCC) at Memorial University, says it can be difficult to know when a student needs mental health support, especially for those coming from places where the conceptualization of mental health and the cultural lens with which they look at it might be different.

Deepanwita says students often feel they can’t talk openly about their mental health because they’re afraid others will think they are “weak”. Studies show that some international students may avoid seeking mental health support due to language barriers or cultural factors. For instance, they may come from countries or cultural backgrounds that place a strong emphasis on individual emotional self-control, and where seeking help for mental health issues is less common.

Fowler says university students are at risk for mental health issues because of the changes they face during post-secondary education. “It’s a time when they move away from home. It’s a time when they have relationship development, relationship issues, academic troubles and stress,” he explains.

Fowler speaks to international students at the beginning of each academic year about the mental health resources available to them, but says, “more of that will probably be great.” On the whole, he says, ensuring students understand the available resources is “a group effort,” and that faculties, professors and staff “need to have an idea of what we do […] to advocate for our services.”

Fowler says the SWCC is also tackling issues that negatively impact mental health, like food insecurity. His own research found that over 60 per cent of international students at Memorial were food insecure. He says increased tuition fees, a higher cost of living, inflation and restrictions on work hours for international students have all contributed to food insecurity amongst students. “It’s been quite surprising that many students are having difficulty meeting their basic needs,” he says.

The SWCC provides weekly drop-in services like Oasis, where students can take part in activities to help relieve stress. During those sessions, students also have access to food so they have “opportunities to have some sort of nutrition during the day.”

The public school system

Many refugee students entering the public school system need a multitude of services to help them integrate into the local community, says Xuemei Li, a professor of education at Memorial University. Li says school counsellors have told her of times when they were not adequately trained to support students dealing with severe trauma from war or persecution, and were essentially “learning on the job.”

Provincial NDP leader Jim Dinn, who was a teacher for 32 years and president of the Newfoundland and Labrador Teachers’ Association from 2013 to 2017, says he has heard stories from teachers about refugee students having panic attacks when a plane would fly overhead, and of students carrying their backpacks everywhere, “expecting that they’d have to leave.”

Dinn says educators have been asking for increased government support to assist with the integration of newcomer children into the school system ever since Syrian refugees began arriving in the wake of the Syrian Civil War.

More than a decade later, he says, English as an Additional Language (EAL) teachers are still understaffed, underfunded, and under-equipped to provide the necessary attention and care newcomer students need. Dinn says EAL educators have contacted him about overcrowded classrooms, understaffing, and issues with education infrastructure like software programs.

Efforts being made to eliminate barriers …

Li says the government has made strides since she first started researching the integration of newcomer students into the province’s education system in 2010. However, there are still barriers that newcomer children continue to face.

When Li began her research, one junior high school in the province offered a Literacy Enrichment and Academic Readiness for Newcomers (LEARN) program for newcomer children who have been out of school for at least two years. Refugee students can miss three to four years of education, on average, due to conditions in their home countries and frequent relocations. Now, multiple schools in the province are offering the LEARN program.

Li says this has relieved some pressure on EAL teachers who are teaching larger classes. Li’s 2018 study found that the EAL student-teacher ratio in a high school she analyzed was one teacher for every 45 students, even though the students’ English proficiency levels and learning needs differed.

In the 2023-2024 academic year, four schools in the Avalon region offered EAL programs, including Holy Heart of Mary High School, Prince of Wales Collegiate, Gonzaga High School and Waterford Valley High. But Li says the amount of time students receive English-language teaching is insufficient. According to NL Schools, in a single year, on average, students spend 900 hours with their classroom teachers and 50 hours with an EAL teacher.

In 2022, the Multicultural Educator Program was launched to help support administrators, guidance counsellors, and teachers. Multicultural teachers and counsellors travel throughout the province, from school to school, to welcome new students, primarily government-assisted refugee children. They assess students’ English-language skills, provide direct support, and assist teachers who may have limited experience working with newcomers. According to the Department of Education, the province has three multicultural coaches and 80 EAL itinerant teachers. Of the 253 K-12 English public schools in the province, EAL supports are offered in 153. The department said the remaining 100 schools do not have students who need EAL support.

Susanne Barbour and Greg Simmons are multicultural educational coaches at NL Schools. Barbour has worked as a coach for three years, and Simmons for two. “We’ve been trying to get out to schools and do professional learning for classroom teachers and school staff on how schools in general can support English language learners,” Barbour said.

Many smaller communities throughout the province have seen a rise in the number of foreign residents. According to Barbour, teachers in these schools — many of whom have limited experience working with refugee students — can access support from multicultural educators and counsellors to help them better meet the needs of newcomer students.

Barbour began working with newcomers at the Association for New Canadians when she was 16. She said she loved the experience so much that she pursued a Teaching English as a Second Language degree.

Simmons, who taught the LEARN program at Holy Heart of Mary High School in St. John’s for 14 years, says he loves being an educator because he is constantly witnessing the resilience with which refugee students overcome their challenges, “despite some really adverse experiences in their childhood.”

… but more change is needed

While EAL teachers and multicultural educators have training and experience working with newcomers, classroom teachers don’t share the same expertise. “Local teachers are challenged because they haven’t received any training in working with a multilingual, multicultural student,” Li says.

Barbour says classroom teachers are “crying out” that students “need more EAL support and would like more time with an EAL teacher.”

Because the province does not have any Teaching English as a Second Language (TESL) Canada-recognized certificate programs, teachers who want to become accredited as a TESL/TEAL instructor must take online courses or travel to other provinces. In her 2018 study, Li notes that while non-EAL teachers expressed a desire to learn about and connect with their newcomer students, they also felt their “hands were tied in terms of how to integrate these students.”

In her research, Li also found that teachers in the province need more “instructional budget, instructional time, workspace, and curriculum guidelines,” and designated school spaces for itinerant teachers.

The province’s education system places children in the same grade as others their age, regardless of their prior education. This is to help children interact and socialize with others in their age group, which can also be overwhelming for refugee students with gaps in their education.

Li says it can be challenging for teachers to assess students’ language abilities or if they have any learning disabilities because of the language barriers, adding that during language and disability assessment, students may speak in broken English, which can confuse assessors. “It’s a very tricky issue for teachers, and we lack the human resources, basically the personnel in schools to determine that,” she says.

During her research, Li found cases where students were incorrectly diagnosed with learning disabilities, which led to them feeling “indignant.” She also reported instances where students’ disabilities were disguised by language barriers, resulting in them not receiving timely educational help. She recommends that disability assessments be made in collaboration with experts in several areas, including EAL and PTSD counselling.

Province needs separate budget for EAL programs, says NDP leader

Research experts, educators, and politicians, including Dinn, have highlighted the lack of an assigned budget for EAL programs. Dinn says teachers have expressed concerns about funding.

In its 2023 budget, the provincial government announced $25-million for school-based reading specialists, teaching and learning assistants, teacher librarians, and EAL teachers. Unlike other provinces, Newfoundland and Labrador does not have a budget line dedicated solely to EAL support. In the 2025 budget, the province allocated $20 million to increasing teaching services, which will “add more than 400 educators and learning assistants.”

Ontario, British Columbia and Alberta all offer a separate budget line for English as an additional language programming. Dinn says a separate budget line is necessary because that specifically-allocated funding would allow EAL staff to plan appropriately for programs, services and resources. Dinn says without it, “you never know what’s available, how much can be spent, how much needs to be added to.”

In an Oct. 15, 2024 email to Dinn reviewed by The Independent, former Education Minister John Haggie said the EAL teachers’ budget is under the broader teaching services budget because it allows “for a more adaptable allocation of resources, ensuring that support can be directed where it is needed most throughout the province.”

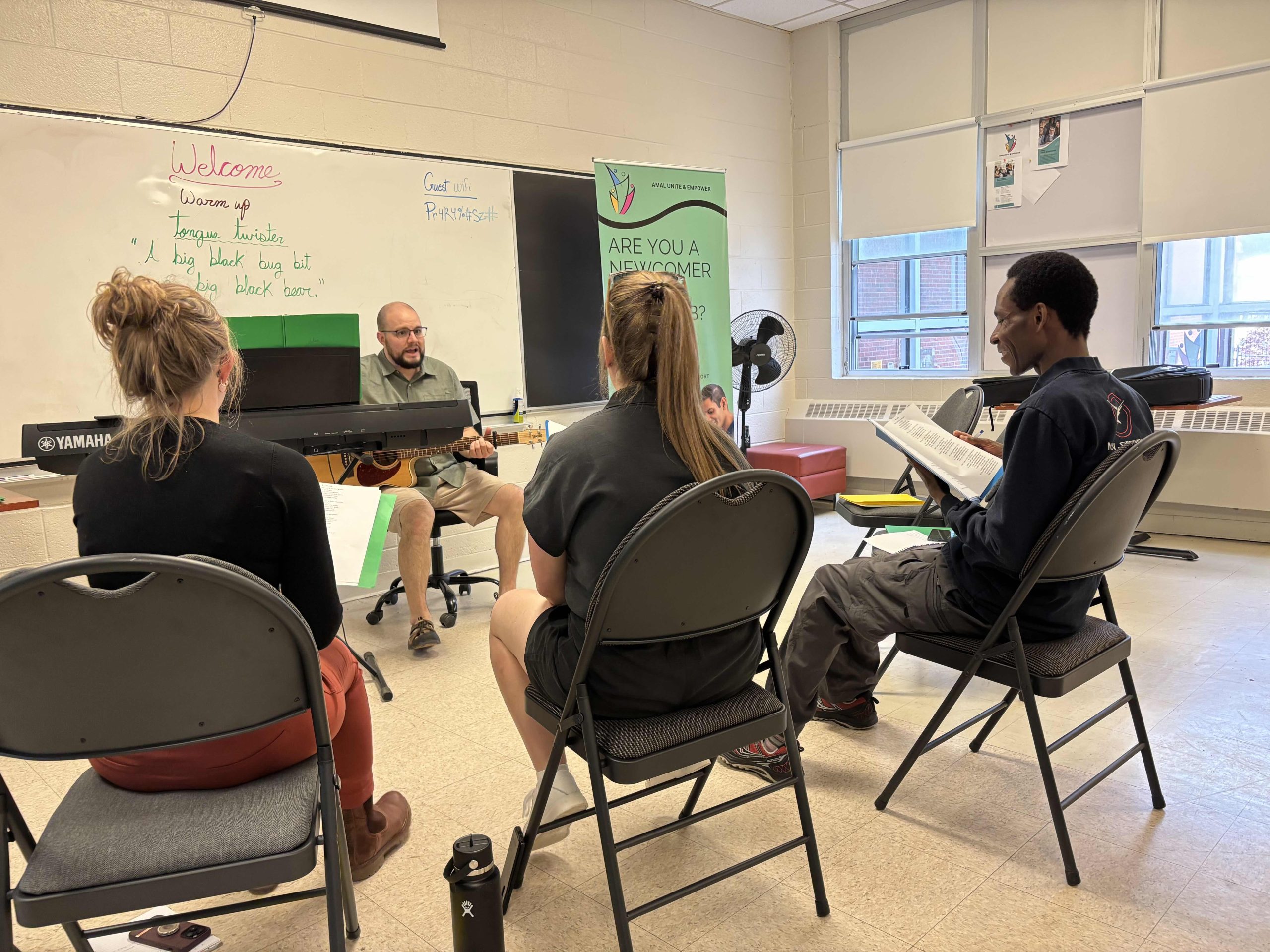

Local groups developing programs

Being away from their home country and culture can be a stressor for young refugees. To help, youth organizations and individual parents are working to improve inclusivity and mental health supports in schools.

Ayse Akinturk, a member of the Muslim Association of Newfoundland and Labrador (MANAL), says that while schools are a great place for children to make friends and integrate into society, youth programs hosted by the association allow Muslim kids an opportunity to meet each other, learn about Islam, and build a strong community.

Program volunteers “are trying to engage our younger youth, school-aged youth, in activities that help them to not only increase their knowledge of the Din [faith of religion], but also social skills [and to] become caring, good Canadian citizens,” Akinturk said.

MANAL hosts Saturday school for school-aged children. For years, the classes were held in the mosque on Logy Bay Road in St. John’s. But due to the province’s growing Muslim population, the mosque can no longer accommodate all of the children. They now hold the school at the Association for New Canadians’ building on Elizabeth Avenue. MANAL also has boys’ and girls’ youth group events for older children to help them learn to socialize with each other. “We take them mini-golfing, bowling, [and] we organize special events,” Akinturk said.

MANAL also organizes field trips to the Mosque for public school students and in-school presentations about Islam and the Muslim community. Akinturk says it allows students to understand the Muslim community and their Muslim schoolmates better than if they were to just read about Muslims in a textbook. She adds that Muslim students who are also in those classes feel “proud” that their classmates can see their place of worship. Akinturk also gives presentations to Memorial University education students about ways they can support Muslim students in their future classrooms.

Sa’adatu Usman is a mother of four who works with schools to teach students about diversity and inclusion, organizing events like multicultural fairs. She says she wants children to accept themselves and feel comfortable in their skin.

Usman founded Global Citizens Inc., an organization dedicated to supporting newcomers and fostering community connections through events and other initiatives like a mentorship program. She partners with schools to teach students about diversity after her four-year-old daughter was bullied because of her skin colour by peers while studying in Dubai. She says the image of seeing her daughter distraught has stayed with her. “I wouldn’t want any kid to go through that.”

Usman says she has received “amazing” feedback since she began hosting workshops in schools. One counsellor at a primary school told her she had “never felt this much energy in the school before,” Usman recalls. What started as a passion project for her has grown, and she’s reaching out to other organizations to help organize events. “It’s just me, and there’s so much need for this,” she says.

The Ukrainian National Federation’s (UNF) chapter in Avalon also hosts a Saturday school program for children to learn about Ukraine’s history, culture, and language. Sofiia Dubyk, the group’s engagement and communications lead, says the program is an effort to help children stay connected with their roots. “We have a celebration like St. Nicholas Day for Ukrainian children. And before Christmas, we will have a Christmas theatre with carols,” she said. The UNF is working on starting English language classes as demand for English after-school programs grows.

Greg Simmons says when he sees his former EAL students around town living successful lives and becoming contributing members of society, he feels “lucky” that he found a niche that “sort of scratched the itch for why we got into it in the first place.”

Dinn says the province needs to retain its residents, but newcomers will choose to settle in provinces where they believe their children will have the greatest chance to succeed. “To me, investing in education is investing in the future of these children and investing in the future of the province.”