Newcomers love N.L. and power economic growth, but lack of supports drive them away

The provincial government and settlement agencies must eliminate barriers that newcomers face when they arrive, say observers, or else the trend will continue

Refugee families feel safer raising their children in Newfoundland and Labrador but many are forced to leave the province in search of better social support and work opportunities.

That’s according to new findings from Nour Khalil, a Memorial University student whose graduate research compares the experiences of Syrian refugees in Newfoundland and Labrador and Ottawa. Khalil chose the topic for her Master’s thesis after learning of the province’s low immigration retention rate. “I was trying to investigate the differences, like their access to resources, to jobs, and the way they experienced resettlement here compared to a larger city where there [are] more immigrants [and a] larger urban population,” she explains.

According to Statistics Canada, the five-year immigration retention rate for newcomers admitted in 2017 was roughly 45 per cent, meaning roughly half of new immigrants left the province within five years — one of the country’s lowest retention rates. Similarly, Newfoundland and Labrador has not done a great job of retaining refugees, with just 36 per cent of those who arrived in 2010 remaining in the province by 2015.

Due to persistently low birth rates—1.22 children per woman of childbearing age in 2022—and an aging population, the province is facing labour shortages in several sectors, including healthcare, construction and early childhood education. Between 1971 and 2021, the number of residents under 20 decreased by 62 per cent, while the number of residents over 65 increased by 258 per cent.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

The number of deaths in the province has surpassed the number of births. Death rates rose from 3,200 in 1971 to 6,100 in 2023. A shrinking workforce affects the amount of tax the government collects, resulting in lesser or constrained public services. Increased hiring from outside the province to curb labour shortages has helped population growth over the last few years. In 20223, the population increased by over 7,000 people.

Newcomers help fill labour shortages, pay taxes, and spend money in the province, but Memorial University Professor of Economics Tony Fang says Newfoundland and Labrador is struggling to entice people to stay.

Fang says the province is ideal for many newcomers because it offers a supportive and welcoming community, a low cost of living, and an attractive natural environment. “It’s a good place to raise children,” he says, adding that the province needs to address the barriers newcomers face, the largest of which include language skills and access to English classes, social integration, and foreign credentials.

Housing, language, transportation, and community important factors in finding work

Laura Aguirre Polo is the manager of Amal Unite & Empower in St. John’s, a non-profit that helps newcomers find employment. Originally from Columbia, she understands how hard it can be to find good work as a newcomer.

Aguirre Polo says there are many barriers to finding meaningful employment and each newcomer’s case can differ. “We have participants from so many different countries, backgrounds, professional experience, academic experience, all types of ages,” she says. “There is also that need to really educate people and society [about] the value that we newcomers bring to this community, to this province.”

Khalil says those arriving as government-assisted refugees have little to no knowledge of the place they are being moved to and must go through several settlement stages before they can start looking for jobs. “Rarely, you would find people finding jobs during the first year, and finding a job actually is very essential for their integration, for their connections, for their success later on,” she says.

Newcomers who are part of the federal refugee program spend several days in temporary homes or hotels until they find a house to rent with the support of a settlement officer, Khalil explains. Then they buy or find donated clothes and other home essentials, attend English language classes, learn the local transportation system and navigate government supports and services.

Aguirre Polo says the province’s housing crisis has presented an additional barrier, explaining it gets “a little bit more challenging for some newcomers when you don’t have a local network when you might not have a reference from a landlord.” She says language is also a major barrier for newcomers looking for work. “We have a lot of people who have wonderful backgrounds, professionally and academically, but if they don’t speak English, it’s very unlikely they will find a position in their field.”

Language barriers are even more pronounced for refugees. Fang’s research found that poor English language skills limit employment opportunities and low-wage work for many refugees, often putting them in difficult financial situations.

Aguirre Polo says few resources exist for refugees and immigrants to learn English. Existing English-language programs offered to newcomers have long waitlists or are offered during work hours, presenting barriers for newcomers with young kids who can’t leave home.

In larger provinces like Ontario and British Columbia, employers frequently hire translators, interpreters and speakers of popularly-spoken languages. B.C., for example, has the country’s second-largest population of people who speak Punjabi. Because of those numbers, Punjabi-speaking jobs are regularly advertised online.

Transportation and a lack of childcare can also impact whether a person can accept a job offer. Aguirre Polo says newcomers might have to take a less-skilled job near their home instead of one that aligns more with their education and goals. A driver’s license is necessary for certain jobs, but car payments and insurance can be higher for newcomers because their driving history from home may not be recognized, Aguirre Polo explains.

When newcomers struggle to find or navigate supports or services, they often rely on community members to help them adapt and settle, which makes integration into local communities essential to finding work and building a strong social support system.

Khalil says older refugees arriving in Canada have less opportunity to meet people and tend to socialize more with others from their own community. She found that Syrian refugees had a larger social support system in Ottawa than they did in Newfoundland and Labrador.

“Connections, here, are very essential in a small city to succeed,” Khalil says. But due to language barriers she found Syrian refugees had fewer chances to interact with English speakers. In more populated provinces, newcomers often connect with others from the same ethnic community, who can later serve as work references to help them secure jobs.

Foreign credential recognition

Khalil says many refugees had businesses or established careers back home, but those experiences and their education may not be recognized in Canada. Around 20 per cent of all jobs in Canada are regulated, meaning that even if workers have years of experience in a profession in their home country, their education and experience still need to be recognized by a Canadian regulatory body. These professions include doctors, nurses, lawyers, pharmacists, teachers, plumbers, and electricians, among others.

Depending on the profession, either the provincial and territorial regulatory authorities are responsible for recognizing foreign credentials. In some professions, federal regulatory organizations work together with provincial regulatory authorities to ensure consistency in recognition, certification, and practice across the country. The Canadian Medical Association and the Canadian Bar Association, for example, both work with provinces to ensure consistency for physicians and lawyers nationwide.

The time and costs associated with retraining in order to qualify for regulated jobs are a luxury often not available to newcomers. Getting degrees recognized in a province or territory is complicated, and many newcomers are forced to turn to low-wage jobs in order to support themselves and their families.

Khalil says the mental health of a family’s primary income earner can be affected when they can no longer provide a quality lifestyle for their family as they did before they became refugees. Fang says if the provincial government streamlined the education- and experience-recognition process, newcomers could help fill the shortages in regulated professions like medicine.

A spokesperson for the provincial immigration department told The Independent that the government is taking steps to streamline and accelerate the foreign credential recognition process. In 2022, the province introduced the Fair Registration Practices Act to ensure registration practices for regulated professions are “transparent, timely and fair.”

The Department of Health and Community Services has also introduced the Ukrainian Physician Licensure Support Program to help Ukrainian physicians who wish to practice medicine in Newfoundland and Labrador. Under the program, Ukrainian physicians can receive up to $10,000 in funding to cover the costs of obtaining licensure in the province.

Discrimination

Meanwhile, some employers just won’t hire immigrants, Aguirre Polo says, explaining some have told her they don’t want to hire specific ethnicities or nationalities. Research suggests employers can also underestimate the work experience newcomers have gained in their home countries.

Fang says that while many employers discriminate against immigrants, those with experience hiring newcomers often report positive experiences. In 2021, of the 301 employers in Newfoundland and Labrador Fang surveyed, 89 per cent who hired immigrant workers spoke positively about their workers, whereas just three per cent reported negative experiences.

As part of the research, 99 employers who had worked with immigrants were asked whether language differences made it difficult to communicate with immigrant workers; 35 said it was not, 39 were neutral to comment, and 29 said lack of language skills were a concern to them.

When newcomers do find jobs, low wages can contribute to their desire to move to a new province. Many newcomers, especially refugees, start with low-income jobs. In her research, Khalil found that of the seven interviewees in St. John’s, only one was earning more than minimum wage. Newfoundland and Labrador’s current minimum hourly wage is $15.60, rising to $16 on April 1. The living wage—the minimum income necessary to fulfill basic needs—is $25.

The low pay and poor working conditions many newcomers endure is a form of exploitation that many employers embrace to help their bottom line. “There are people who actually see immigration and newcomers as a source of cheap—or sometimes even free—labour,” says Aguirre Polo.

Pre-arrival information gaps

Khalil says the federal and provincial governments must offer accurate pre-arrival information about life in Newfoundland and Labrador, including the province’s winter conditions and other basic information about housing and transportation, so refugees can make informed decisions and better prepare for their settlement process.

Nancy Caron, a spokesperson for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, says pre-arrival information is offered through the department’s Canadian Orientation Abroad program and implemented worldwide by the International Organization for Migration. The organization’s pre-immigration in-person training for those selected for refugee status in Canada is 15 hours over three days. The information shared during these sessions is focused on Canada as a whole, rather than being specific to any one province.

Khalil says refugees should have access to a job-search program, and the government must invest in more entrepreneurial programs for newcomers. In 2022, in partnership with the Association for New Canadians (ANC), the province launched a program to help Ukrainians find work in the province. The government displayed ads asking local businesses to hire Ukrainians. Within a year, over 700 Ukrainians had found work through the ANC. In 2023, the provincial government provided $11 million to support Ukrainian employment and housing.

Aguirre Polo says employers need more cultural-sensitivity training, and that the government must improve policies to reduce barriers for newcomers to access safe and meaningful work. This includes lifting restrictions around international student work hours to allow them to gain work experience and making it easier for newcomers to access MCP. To gain access to the province’s health care, a non-resident must have worked in the province for six months to a year, which can leave some newcomers without health coverage.

- Related: MCP is For Some But Not All

Fang’s research on employer perceptions of hiring newcomers and international students recommended the government provide more support—including immigration information, funding, and legal support to encourage the hiring of newcomers—to small- to medium-sized businesses, especially those in rural areas. The report notes that “medium-sized businesses and businesses located in rural areas are less likely to hire immigrants, even though they have experienced more acute labour and skill shortages.” The report also suggests government work with employers and training institutions to improve job-specific language training and bridge programs.

Aguirre Polo says people who have just arrived in Newfoundland and Labrador are very excited and hopeful, but she has witnessed people who have lived in the province longer feel discouraged when they cannot get jobs.

More settlement agencies needed

The Association for New Canadians is the province’s primary settlement agency. Khalil, who worked at the association as a settlement health worker in 2022, says one settlement agency isn’t enough because of the large number of refugees entering Newfoundland and Labrador. “It’s a huge burden on them and people seeking help,” she says.

Between April 1, 2022, and March 31, 2023, the province welcomed roughly 102 privately-sponsored refugees, 699 government-assisted refugees—a 59 per cent increase from the previous year—and 2,600 Ukrainians. The ANC was responsible for settling government-assisted refugees and many Ukrainians, in addition to helping those who had arrived in previous years, as well as other immigrant groups like international students and temporary foreign workers.

Khalil says having multiple agencies would ease the burden on the ANC and create job opportunities since many newcomers are hired by settlement and family services agencies. “It would also help people seek help from different places, so if they were not successful in getting what they want in one place, they have another place.”

Khalil adds that while the ANC focuses on all aspects of settlement for refugees under government assistance, and Ukrainians who came to the province on special visas after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, other agencies could alleviate the systemic burden by specializing in different aspects of resettlement. “Some of them can focus on employment, for example. Some of them can focus on finding houses.”

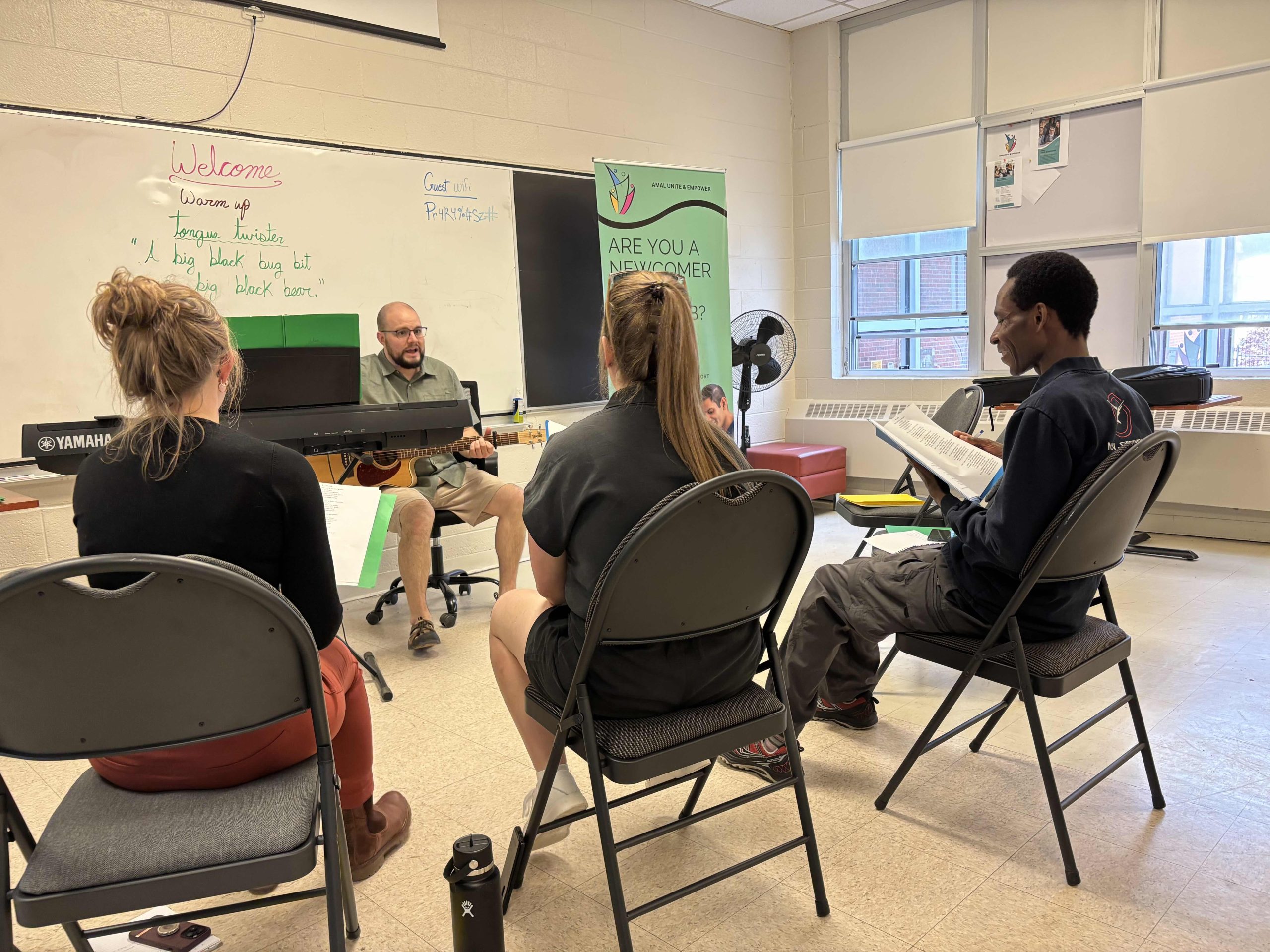

Aguirre Polo says the Amal Youth and Family Centre is trying to fill those gaps. Founded in 2021, the organization provides various services to the community, particularly newcomers. Amal’s Unite & Empower program, launched in February 2024, aimed to find employment for 240 applicants in two years. Aguirre says they have received over 600 applications and have helped over 114 newcomers so far.

Khalil says she admires Syrian refugees most for their resilience and for working to establish themselves in the face of adversity. “They have future dreams,” she says. “And being able to dream and hope and plan after everything you’ve been through is really important.”

If you are a newcomer and want to share your experiences settling in Newfoundland and Labrador, please email editor@theindependent.ca. This article is part of The Independent’s Coming to Newfoundland & Labrador series. Click here to read the other stories. The series was made possible through the financial support of Carleton University’s Emerging Reporter Fund on Resettlement in Canada.