N.L. continues to fail its seniors, province’s advocate concludes in annual report

Seniors’ Advocate Susan Walsh says Newfoundland and Labrador has the “oldest, poorest and most unhealthy seniors in Canada,” in report that paints a grim picture of what life is like for many residents 65 and older

Homelessness among seniors is on the rise in Newfoundland and Labrador, the province’s Senior Advocate warns in a new annual report released Thursday.

“The rates of seniors [in] shelters are nothing short of startling,” Susan Walsh told reporters gathered for the report’s release at a Holiday Inn in St. John’s.

According to the Seniors’ Report 2025: Monitoring Key Indicators of Seniors’ Wellbeing in Newfoundland and Labrador, 21 per cent of emergency shelter users are 55 or older, and 9 per cent of those who report experiencing homelessness for the first time are in that same age bracket.

“Newfoundland and Labrador has the oldest, poorest and most unhealthy seniors in Canada, and in most cases, has the lowest access to services, especially in rural Newfoundland and Labrador,” Walsh said Thursday.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

The 88-page document outlines how seniors in the province are doing by analyzing data on six key indicators: well-being, individual health, health care, finances, housing, transportation and safety and protection.

The Office of the Seniors’ Advocate issued its first baseline report on seniors’ well-being last December, finding that Newfoundland and Labrador lagged behind the rest of Canada in several key areas. For example, the 2024 report found that seniors in the province earned $27,800 annually, 17 per cent less than the country’s average income among seniors. Seniors in the province also consume only 14 per cent of the recommended intake of fruit and vegetables, compared with 26 per cent nationally.

The 2025 report shows the province has made little progress in improving senior well-being. “It is frustrating,” Walsh said, “They [seniors] are hurting in this province, and they’ve done so much for the development of our province. I mean, our seniors built this province. They had big families, they paid their tax.”

In 2023, seniors in the province earned a median income of $29,700, the lowest in the country. At 51 per cent, seniors in the province also have the highest reliance on income transfers in the country, such as Old Age Security and Guaranteed Income Support.

As winter approaches, Walsh said some seniors will be forced to think about what bills to cut. “‘I have to put some heat in this house. I might shut off some bedrooms. I might shut off down upstairs […] but then I can’t pay my bills for other things, so I’ve got to cut back on food.’”

Food security amongst seniors in NL has also dropped, with a greater number of seniors experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity. The report suggests insufficient income is a contributing factor to senior food insecurity.

Healthcare services

In 2023, 84 per cent of seniors in the province had a primary healthcare provider compared to the national average of 92 per cent. The report also notes that as of July 31, 2025, approximately 10,657 seniors are on the waiting list for a primary care provider.

Walsh said there are 25 beds per 1,000 seniors in the province’s long-term care facilities, adding the distribution of these facilities across the province is not equal, leading to even longer wait times in rural areas.

“While I’m not advocating for more long-term care beds, until we address the needs in the community and the supports and services that seniors need in the community, this is going to be our reality,” Walsh said.

Long-term care residents in the province also experience more pain, physical restraint and potentially inappropriate use of antipsychotics than the Canadian average. During 2023 and 2024, 12 per cent of residents in the province were restrained, compared to the 5 per cent national average.

“The frequent use of restraints is an indicator of potentially poor care,” Walsh said, explaining repeated use of restraints can impact a senior’s ability to carry out daily activities, impair cognitive functions and increase the risk of bed sores.

Seniors fare worse outside urban areas

While more seniors live on the Avalon Peninsula than in any other single region, the majority of seniors live in other parts of the province and make up almost one-third of the populations of the Eastern rural, Central and Western regions, where Walsh says services are lacking.

She notes that in 2023 and 2024, the potentially inappropriate use of antipsychotics in long-term care was 32 per cent in the province compared to the national average of 25 per cent. “This means that one in three prescriptions for antipsychotic medications are considered potentially inappropriate,” Walsh writes in the report. She also notes it is “quite concerning” that the number in the Labrador-Grenfell region is estimated at 45 per cent.

Walsh said a focus on preventive community services is “critical to ensuring seniors maintain their health and well-being and can access the services they require to age in the right place.”

She said “the most important thing” government can do is introduce continuum of care legislation, which she recommended in a May 2025 report to the province on long-term care and personal care homes. “A strong governance structure is necessary to ensure that the long term care and personal care home systems are fixed and these systems, and those responsible for their oversight, are held to account,” she said in May. “The creation of legislation focused on the full continuum of care that seniors require, from home support through to palliative care, will set the standard for each of these services and ensure those responsible for oversight are clear on their roles. We owe seniors this diligence given they are paying for these services yet receiving little value in many cases.”

On Thursday Walsh added that, “once the legislation is there, then that sets the framework and requires government to follow it, and the money will follow that.”

She’s also concerned about a 64 per cent increase in violations against seniors in the last five years. “I have heard from many seniors, especially in rural Newfoundland and Labrador, about their concern for their safety.”

Her report notes that although crime against seniors decreased according to data from the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary—which primarily operates in urban areas—over the past year it has increased 12 per cent according to the RCMP, which operates in rural regions.

“We heard about a situation when I was on the Northern Peninsula, where they actually had to take action as a community themselves against the perpetrator, because the police weren’t going to get there for over a day,” Walsh said.

Community culture plays a significant role

One area where the province fares better than the rest of Canada is in life satisfaction and a stronger sense of community belonging.

Seniors in Newfoundland and Labrador reported higher positive feelings of satisfaction with their lives and a stronger sense of connection to community than the Canadian average. “We are only lucky that we have such a caring society in Newfoundland and Labrador and families who won’t see their loved one go into long-term care because they know what it means,” Walsh said.

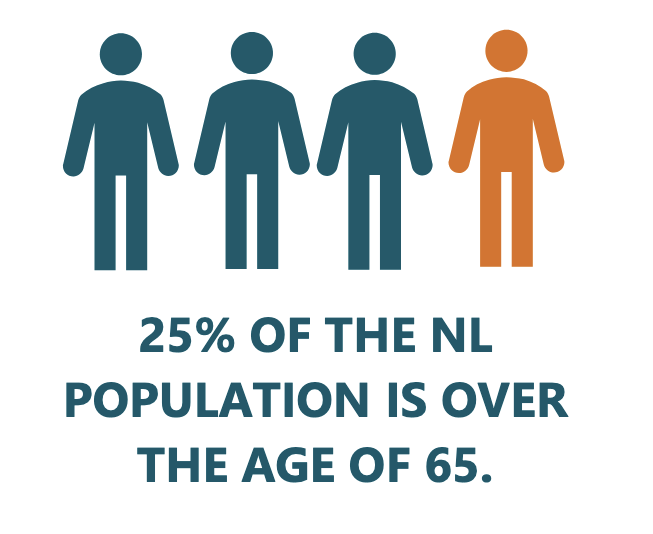

The demand for seniors’ services will continue to grow as the province continues to age. In July, Newfoundland and Labrador became Canada’s first jurisdiction to have one in four residents aged 65 or above. If the province does not invest in community supports and services, then “the demand for costly, unwanted institutional care is going to continue to increase,” she said. “It’s inevitable if we don’t support them early. It’s all about prevention and earlier intervention and community supports.”

Part of that solution is to move away from a one-size-fits-all approach and design programs based on community needs. Rural areas where needs are even greater are underserved, Walsh said.

The seniors’ advocate said she would like to see free home support. Seniors who cannot afford home support end up in long-term care centres earlier than they need to, instead of aging in place. The report emphasizes that living at home helps seniors maintain their independence and remain engaged in daily activities, including regular interaction with family, friends and community.

Walsh said the reports released by her office are leading to acceptance that many seniors in the province are living in poverty and lacking support. “Change takes time and government moves slowly,” she said.

Walsh has not met recently-appointed Progressive Conservative ministers yet, but has written to them.

Read or download the Seniors’ Advocate full annual report.