PCs ‘not prioritizing’ review of AI policies following Education Accord scandal

The province’s new 10-year policy document will guide changes to Newfoundland and Labrador’s education system, but reports of falsified materials have cast a shadow over its credibility

In the wake of a scandal involving the province’s new Education Accord, which contained fabricated sources and has led many to believe artificial intelligence was involved, a spokesperson from Premier Tony Wakeham’s office told The Independent the new PC government is “not prioritizing” a review of its AI policies.

In September, the 10-year education plan came under scrutiny after several incorrect citations were found, which some have suggested could have been generated by AI. An access-to-information request from blogger Matt Barter shows the province spent more than $755,000 on the report, which the government described as a roadmap to modernize Newfoundland and Labrador’s education system.

Wakeham said during the election campaign that a Progressive Conservative government would thoroughly investigate the report and that he would discuss the report’s findings in detail with the authors. The PC leader also told the Newfoundland and Labrador Teachers’ Association his government would publish the accord in full, “not an edited version prepared by the government, so that the people of Newfoundland and Labrador can see the original work without political interference.”

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

James LeBlanc, an associate professor in Memorial University’s Department of Physics and Physical Oceanography, says that if the false references in the accord are a result of AI, the incident raises concerns that policymakers lack a clear understanding of artificial intelligence and its applications within government processes.

LeBlanc says the discovery of false sources in the report has left “a stain” on a critical policy document, and that educators in the province need to be able to trust government reports without question.“We want to be able to just read a line and know it’s true and not have to go hunting out to determine if it’s correct or not.”

As public institutions learn to integrate AI into their systems, they bear a responsibility to remain adaptable and responsive to the technology’s rapid evolution, says Janna Rosales, a teaching professor in Memorial University’s Department of Engineering and Applied Science.

Lack of scientific rigour

In September, then-Education Minister Bernard Davis told reporters that AI was not used to create the Education Accord, stressing the errors did not impact the body of the report or its recommendations. At a press conference, he said it was “preposterous to even think that someone would type in AI. Let’s give us an Education Accord of 118 pages with 450 citations to assume that AI is going to generate a document of that nature. It’s too foolish.”

The roughly 400-page education plan, developed over an 18-month period, contains 110 recommendations and calls to action aimed at enhancing early childhood education, K-12 education, post-secondary education, and adult learning. According to CBC, it contains at least 15 citations that don’t actually exist.

The document has since been removed from the Education Accord NL website. According to the Department of Education, it will be available online again once the errors have been corrected.

On Sept. 15, the report’s co-authors, Anne Burke and Karen Goodnough, told CBC the errors must have happened after they submitted the report to the government. “We don’t know where the errors were made; we can only assume that it happened with the government.”

LeBlanc is also concerned about the lack of scientific rigour in parts of the accord, explaining he expected the document to include multiple references to support certain statements. “The reason why it’s so easy to find fake references in the document is that some of those really key fundamental statements are followed not by […] dozens of references, but instead by a single fake reference that presumably has been generated by AI.”

He adds that while the use of artificial intelligence isn’t inherently problematic—for example, to create a one-page summary of a lengthy document—it’s important to clearly disclose this information. He says AI tools tend to produce inaccurate information and fabricated references, and that responsibility ultimately falls with the author to verify the content and ensure the information is reliable.

Aaron Tucker, an Assistant Professor in Memorial University’s Department of English, says while he cannot definitively say AI was used in the report, “the fabricated sources […] speak to a lack of attention and maybe a lack of transparency.” Tucker is the lead of a project titled The New Past: A History of Canadian AI as Techno-National Project.

A flexible and responsive policy

The provincial government has implemented a Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence Technology policy for its public service employees. In May 2025, then-Minister of Government Modernization and Service Delivery Sarah Stoodley said the government was in the process of providing AI training for all government employees.

AI technologies are evolving so rapidly that institutions struggle to keep up with them and implement the necessary policies to ensure artificial intelligence systems are used responsibly and effectively, says Rosales, who researches technology and ethics.

Rosales says the best way to develop a strong AI policy is to ensure it remains “flexible and responsive” to ongoing technological changes. Maintaining such a policy “involves multiple interest holders and isn’t top-down, or prescriptive, or one-and-done.”

To achieve this, institutions must get everyone on the same page about what their boundaries are as an employee of a public institution on what you can or can’t do. Employees’ voices and perspectives should also be heard and considered to ensure everyone’s thoughts are aligned. “There’s a fair amount of deliberation that has been involved around how you use it, to what extent you use it—and even now, what tasks it could be used for,” Rosales says.

Ideally, she adds, public institutions should be able to adapt quickly to the rapidly changing AI landscape. Rosales explains if a policy is developed based on the state of AI but takes 18 months to move through an approval process, the technological landscape would have already shifted, leaving the policy outdated before its implementation.

It’s also important to include an AI disclosure statement in any good policy. “That at least acknowledges that AI—whatever the particular platform, whatever the particular version—was used to collect references, or to use for proofreading, or to summarize material,” she says.

Tucker says the issue isn’t the use of AI in government documents, but rather ensuring that whenever artificial intelligence is used authors are transparent about how it was applied, what type of AI was used, and in what context. “Otherwise, it’s very dangerous to kind of dictate, let’s say, public institutions based on non-transparent use of artificial intelligence.”

Artificial Intelligence training should include awareness of the technology’s limits, says Tucker. “It’s not very good at reading large, complex texts. It will hallucinate.” Tucker says the software may also hold biases depending on what it has been trained on. “There’s a long history of it being kind of racially biased, gender biased.”

Tucker also notes that AI tools are developed by private corporations whose primary motives are profit. As a result, the goals and principles behind these tools may differ from those required in a government context, given the specific needs and ethical standards which govern public institutions.

Rosales says public institutions often handle sensitive information that must remain within their control, making it essential for employees or students to only use AI tools that their organization officially approves.

Reactions to the report

LeBlanc says the damage to the report’s credibility has been done. “If they turn around with a new document […] even if they fix the references, it leaves sort of a black stain on the document.”

The physicist began reviewing the report himself after reading the CBC article alleging that at least 15 of the report’s more than 400 references were inaccurate. When he found some of the false references, he was disappointed. “This is a policy document that’s supposed to be evidence-based, that’s supposed to help guide policymakers on how to spend money to improve education outcomes.”

NLTA President Dale Lambe has said he’s concerned about the scandal. “Teachers across this province participated in the accord process in good faith, providing their time and considerable experience and expertise with an expectation the drafters of this report would produce a credible document at the end of day. Unfortunately, that is now in question,” he said.

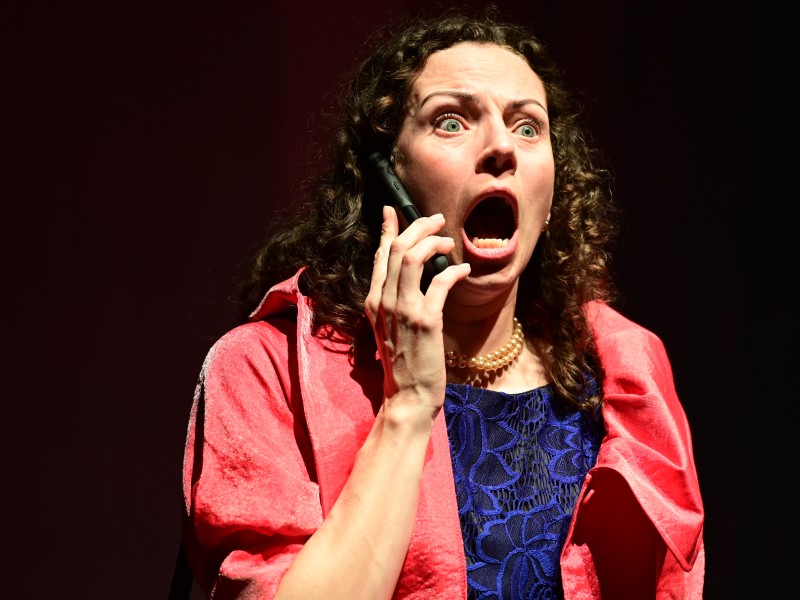

NDP Leader and former NLTA President Jim Dinn said in September it was “shocking and disturbing” that the accord contained non-existent sources. “It’s purely unacceptable that a report like this, one that is meant to enhance and transform our public education system, would have AI-fabricated sources,” he said. “Is this the priority and oversight this government puts into our education system? Is this what they consider good consultation and research?”

‘Solid core message’

Burke and Goodnough, both professors in Memorial University’s Faculty of Education, consulted a range of stakeholders, including Indigenous governments and other organizations, advisory committees, disability advocacy groups, health and well-being experts and education workers. They did not respond to The Independent’s requests for comment by the time of publication.

Paul Walsh, CEO of the Autism Society of Newfoundland and Labrador, whose group was part of the initial consultations, says he is “hopeful” after seeing the final document and pleased the Autism Society was asked to participate in its implementation process.

Walsh says the final report addresses concerns his organization had following the release of the interim report in January. Last July, he criticized the accord’s interim report for failing to focus on students with disabilities.

He says the report’s success will depend on how the recommendations are implemented, but adds it was refreshing to see the Department of Education use language that is more neuro-inclusive, and to forgo words like exceptionalities, “which is so commonly used in education and it’s such a derogatory term.”

The now-unpublished document includes recommendations to support learners’ diverse needs, provide training for educators to address individual learning styles, and upgrade infrastructure so that learners with physical disabilities are not excluded.

Walsh hopes the controversy around the fabricated sources doesn’t take away from the “very solid core message that this report provides.”

“It is embarrassing to the Liberal government that the Education Accord contains errors. When a report that is supposed to guide the future of education includes mistakes, it creates doubt among readers and undermines its credibility,” Wakeham said in his response to the NLTA.

He said his government will sit down with teachers and the NLTA to examine the recommendations, and that the PCs “will not take a blanket approach to accepting or rejecting the Accord.” Instead, he said they will review the document recommendation by recommendation, “fact-checking the assumptions behind each one, and consulting with stakeholders on how the proposed changes would affect teachers, students, and classrooms.”