Wakeham says PCs will implement promises not in party platform

The premier’s statement comes days after Wakeham mandated his cabinet to prioritize commitments in election platform

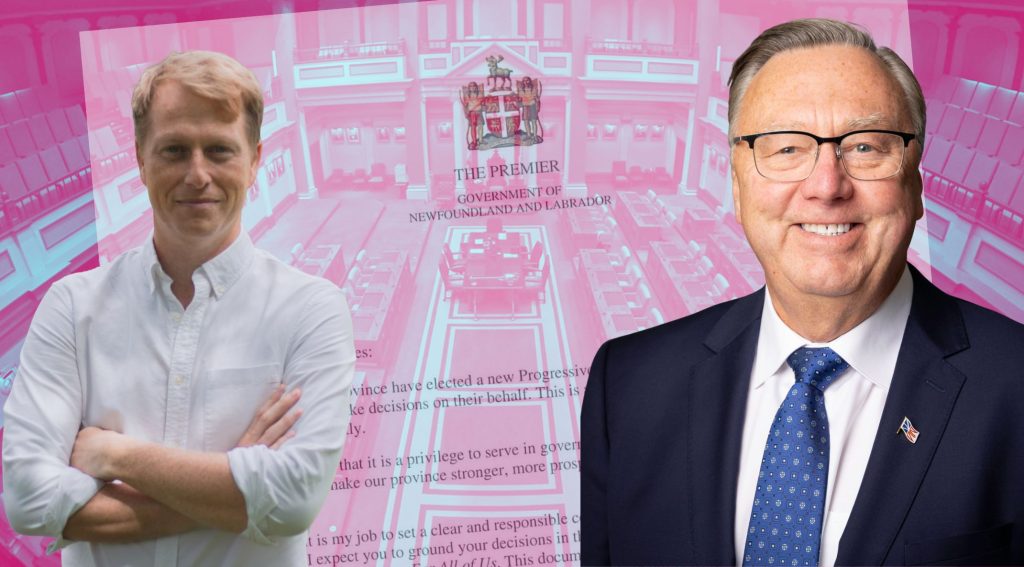

When Premier Tony Wakeham issued a single mandate letter to his cabinet ministers earlier this week instructing them to fulfill the Progressive Conservatives’ promises made in the party’s election platform, it wasn’t clear what that meant for all the promises the party made during the election campaign which were not listed in the platform.

On Thursday Wakeham provided clarity on the issue.

“Premier Wakeham looks forward to implementing all the commitments he made during the election campaign, including those to stakeholder groups,” Ashley Politi said in a statement to The Independent on behalf of the premier’s office.

Wakeham’s office was responding to questions from The Independent about whether the promises the PC leader made in questionnaire responses and interviews with labour leaders, such as the Registered Nurses’ Union (RNU), NAPE and the NL Federation of Labour.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

For example, while the PC platform promises major improvements to the province’s healthcare system, including how healthcare is delivered, Wakeham told the RNU a PC government would specifically “create a permanent province-wide team of local, Newfoundland and Labrador nurses and Nurse Practitioners [to] complete locums in different parts of the province, when and where they’re needed most – especially in rural, remote, and underserviced communities.”

Wakeham also told the nurses’ union the PCs “are determined to implement this quickly,” and that they “will do so in lockstep with the Registered Nurses’ Union and will listen to your advice on the size and composition of the team, and where and when locums should start.”

RNU President Yvette Coffey says Wakeham’s pledge to create a permanent province wide team of local registered nurses and nurse practitioners “was significant,” and “would help reduce reliance on costly private travel nurses.” She also says living up to that promise would “strengthen care in rural, remote, and underserviced communities.”

But Coffey has “no immediate concern” over the exclusion of that commitment from Minister of Health and Community Services Lela Evans’ mandate letter. “The Premier made very clear commitments to nurses during the campaign. We expect him to fulfill those promises,” she says in an emailed statement to The Independent.

“Our nurses are dedicated and skilled. They want to work in these communities. Government needs to give them compensation and the freedom to do the work they are trained to do and want to do,” she says. “Continuing to pay locum premiums to our nurses is far more sustainable than the exorbitant dollars spent on private agency solutions.”

Coffee says the union is in talks with the government and that they “need to see movement and progress now,” explaining the question the RNU put to Wakeham and other party leaders during the election campaign “came directly from the day-to-day experiences of our members,” and that they “fully expect energy and investment in addressing and finally resolving the outstanding issues facing our members and the healthcare needs of the people of Newfoundland and Labrador.”

The RNU is “watching closely,” Coffee says, and is “prepared to hold government’s feet to the fire if we sense any reluctance or slowdown in meeting these commitments.”

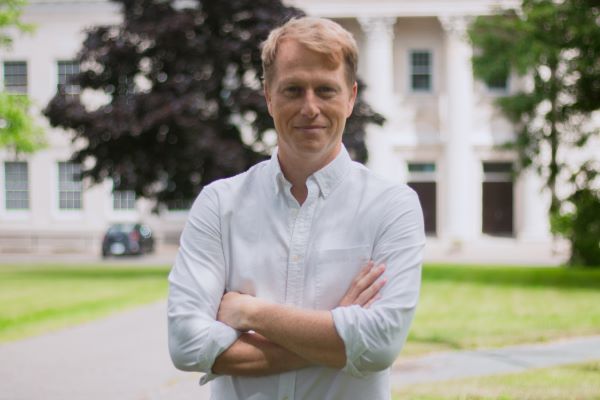

Mandate letters a double-edged sword: prof

Alex Marland, a political science professor at Acadia University and Jarislowsky Chair In Trust and Political Leadership, says the function of madate letters has evolved in recent years.

As first, the letters were “internal private letters from prime ministers and premiers that basically provided a laundry list of activities a minister was meant to accomplish,” he explains. “I’ve interviewed ministers in various capacities who have told me that they were laser focused on completing all those activities, and would go back and ask for more if they were able to accomplish everything.”

Then, in 2015, then Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and a few premiers made their mandate letters to cabinet public in the name of transparency and accountability. “That changed things because on the one hand […] it allowed transparency, it allowed the public to see what ministers’ priorities are,” and it was “very helpful for public servants [who] could look at it and say, ‘Okay, now I know what my department’s or my minister’s portfolio, like, what the priorities are here,’ so they provided that level of clarity,” Marland explains.

On the other hand, he says, “because they became public documents, they also became very performative.” Marland says the nature of public mandate letters meant political leaders used different language. “There was a lot of things in them that was kind of fluffy and they weren’t very specific.”

Earlier this year Prime Minister Mark Carney issued a uniform mandate letter to his cabinet, a move Wakeham followed this week.

“In some ways we’re back to the way things were before Justin Trudeau,” says Marland.

An ideal scenario for government transparency and accountability, he explains, would be a “new tradition” for mandate letters. “In early January every year, every premier and every prime minister could say: these are the priorities of my government for this upcoming year.”

But that’s not likely to happen, Marland says.

“I just don’t think they’re gonna do it because they don’t want that level of restriction. Because then what happens is, if you don’t accomplish what you set out to do, then people will be pissed off at you,” he says, adding it often takes time to implement legislative or policy changes. “So I think ultimately what happens is governments just realize it’s not worth the headache. There’s just too much critique, and so it’s better to be critiqued for not releasing them, for not preparing them at all, than it is to go ahead with it.”

Constituents like to judge PCs on ‘high-level overall values and general commitments’

All governments make promises that “don’t necessarily always materialize […] but especially when a party is coming from opposition into government,” Marland explains. “It’s really hard to act on all those promises and they often will distance themselves, because you say things during an election campaign—you develop a platform—but you don’t have the benefit of the wisdom of the public service.

“Often what happens is you form government and all of a sudden [public servants] say, ‘Well, here’s five reasons why you can’t do this.’ And you had no idea on the outside about these things because they weren’t publicly available or you didn’t have 20 years of institutional expertise to be able to tell you what is viable.”

Regardless of any specific promises, “as a society we should be concerned if politicians are making promises and then get into government and walk away from those promises,” says Marland. At the same time, it frustrates him when people respond with the “generic statement: ‘Well, you can’t trust politicians. They make these promises and they don’t fulfill ’em.’

That line of reasoning “weakens people’s confidence in democracy overall,” he says. “At the same time, I think there is obviously a need for some leeway for a party that forms government and then has the benefit of the public service, helping them figure out what to prioritize.”

Marland thinks Newfoundland and Labrador’s new PC government will ultimately be judged on their “high-level overall values and general commitments,” like healthcare.

“If they don’t deliver on healthcare overall, that’s going to be a problem for them,” Marland says. “If they made a little promise or smaller promise, it matters a lot to a smaller group of people but has nothing to do with the big picture, overall brand values that they’ve been communicating. I think a lot of people will forgive them for that. But they will not forgive them if they don’t deliver on healthcare.”

Same goes for the Churchill River MOU with Quebec, he says.

“There’s certain big-picture promises that they absolutely have to move on, but individual little promises, you know, I think people will understand if they pivot or they delay, or if it’s not an immediate priority.”

The Independent is tracking the PC government’s promises, both those made in and outside the party’s election platform. Bookmark our Government Promises Tracker to stay up to date.