Friday evening began pleasantly, with members of MUN Students For Palestine enjoying an outdoor barbecue. They were aware Memorial had sent employees in the Arts and Administration building home early, and at the barbecue they discussed whether the university’s intent was to use this as an excuse to file for an injunction to remove student protestors from their 45-day occupation of the building’s lobby.

Earlier in the day, Memorial asked how much longer students intended to maintain the occupation, and the protestors’ lawyer responded that he would meet with students on Monday to discuss the matter.

Two hours later, police raided the occupation, without an injunction, and without warning.

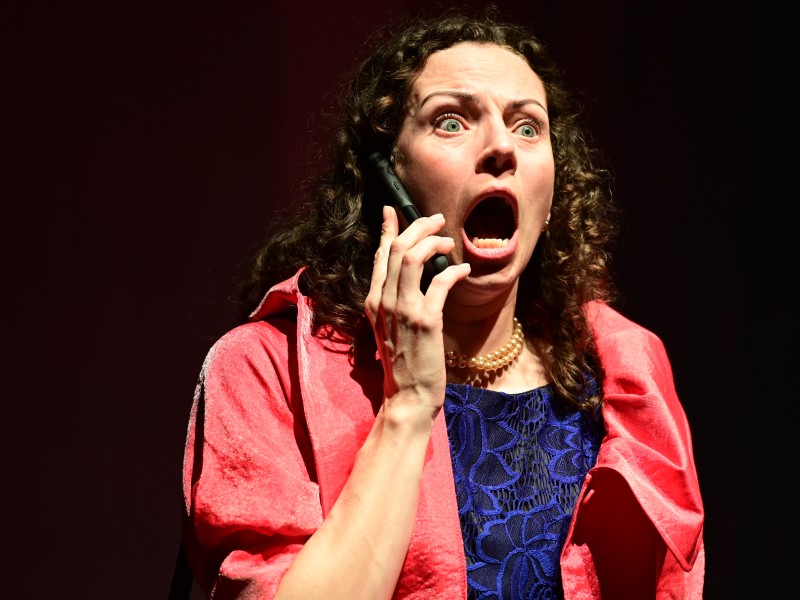

Students who were gathered inside the lobby said they became aware around 9:30 p.m. that campus enforcement officers were outside at the campus encampment with trucks and were removing tents. Several students left the lobby to find out what was going on, while two students remained in the lobby, they said. Moments later, more campus enforcement officers arrived and began shutting and locking access doors to the lobby; Hanaa Mekawy was seated in the lobby when it happened.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

“It was scary being there alone, not knowing what was going on, and then to see this big scary guy who starts locking the wooden doors on us,” she said. “We were doing nothing, we were just sitting in silence, and they started doing that to intimidate us and scare us, to force us out.”

Students outside became aware of the additional campus enforcement presence and rushed back to the lobby. A few made it back inside before officers managed to lock all the doors. At this point, students said, those inside were given a verbal trespass warning ordering them to leave the building. They asked for a written copy of the order and officers refused to provide one but allowed students to photograph the script they had just read.

“Failure to comply will be considered a trespass and intervention by police will be requested,” reads the warning, which protestors shared with The Independent. While students discussed what to do, RNC police officers also appeared. Students say they were told that they would be given a brief period of time to respond to the request.

At that point, students said some of them opted to leave and join the growing crowd of students outside the Arts building, while three remained inside the lobby and refused to leave.

Students and reporters outside watched through the building’s glass doors. At one point seven RNC officers and three campus enforcement officers loomed over the three protestors inside, who sat together holding photos of slain Palestinian children. More officers paced in the hallways outside the lobby, while others lounged in the glass entryway. As students remained seated clutching the photos, an RNC officer set up a camera on a tripod and began filming them.

Outside, more students arrived, pulling up in vehicles and arriving on foot from nearby residences. Some carried Palestinian flags; some were crying, while others shouted angrily at the officers inside.

“I received an email from Memorial’s president talking about students occupying a building,” said one student angrily, referring to an email sent over the university newsline earlier in the day criticizing the occupation. “At least now they know how it feels, having your country occupied.”

After about half an hour, with the seated protestors refusing to leave, campus enforcement officers took protestor Nikita Stapleton by the arms and, flanked by RNC officers, took Stapleton into a side hallway. Officers shut the doors on either side of the hallway so that observers could not witness what was happening to Stapleton inside.

Stapleton later said she was charged under the Petty Trespass Act and given a court summons. Officers told Stapleton if they could get the other two students to agree to leave, then those students wouldn’t be charged. Stapleton returned to communicate the offer, and both students refused to leave. They remained seated, holding tightly onto the photos of slain Palestinians. They were then taken by officers, one by one, to the sealed-off corridor, where they were charged. Each student was then released to the crowd of cheering supporters outside.

Shortly thereafter, the RNC officers left. Campus enforcement officers remained and resumed taking down tents and loading them into trucks. The officers were confronted by the large group of students which had gathered outside, and following some discussion officers agreed to let students dismantle the tents and remove other items themselves.

By this point it was after midnight, but students were still arriving in cars and trucks, into which students loaded materials for transport off campus.

The following day, one of the students who was charged, Sadie Mees, reflected on what transpired.

“Having the police there and having all the campus security looming over us was certainly scary and it was definitely shocking,” she said. “But if we have some perspective, there are people being murdered, there are war crimes being committed, there is torture happening, people are starving to death. Of course we were uncomfortable in that moment, but it’s nothing compared to what [Palestinians] are going through. And if the choice is to be silenced or be arrested, we will do what it takes to bring attention to the fact there are unbelievable atrocities happening right now and something needs to be done about it.”

Devoney Ellis was another of the students charged.

“It was really intense, and ridiculous,” they told The Independent. “We’re sitting there and we’re holding these pictures of martyrs. We’re there knowing that we are protesting our university’s involvement in genocide, their profiting from genocide, the fact that there are real lives being lost here, and they are spending resources to intimidate us?” Ellis continued.

“It was really disgusting and disturbing, this use of intimidation. I’ve spent five years at this university, learning about injustice and oppression, learning about colonization from professors who were actively teaching me decolonial theory and how we need to not be maintaining this legacy of colonization. And then to see the absolute betrayal against faculty and students,” they said.

“I was just like, I have to be here. I’m not going to comply as you tell me that I need to get out of my university, that I don’t have a right to protest in my university. That’s just not going to happen. Everyone always thinks that they’re going to stand up against oppression, and as I was growing up and learning about injustices in the world and oppression, I always thought: ‘What are we going to do?’ And as this was happening I realized: ‘This is it! And this is what I’m doing.’”

“A lot of people were really fearful, just because of the unknown of it all,” Stapleton reflected. “We had talked to our lawyer earlier in the day and he was going to look into the possible consequences and get back to us on Monday, so really we didn’t have an opportunity to know what everything would look like.

“The fact that racialized and international students were able to avoid being arrested that night, and the fact that things ended with people being physically safe, is to the credit of the students involved and the way that they were able to remain calm and collected in the face of this pressure,” Stapleton said.

“Zero credit to the fact that this didn’t turn into a horrible situation goes to MUN because everything that they did lined it up to be a chaotic and very irresponsible and dangerous situation. It was only for the calmness of the students involved that it was able to be resolved in a way that at least people’s physical safety were intact.”

‘Free speech and protest are the very lifeblood of our democracy’

Asked by The Independent why police were brought in, the RNC officer supervising the operation said that “[e]veryone has the right to protest,” and that “this was an issue around the Petty Trespass Act, plain and simple — that’s all.”

The Independent spoke with lawyers and civil rights experts who say the situation regarding Canadians’ Charter rights to protest on university campuses is far from a settled issue, and in Newfoundland and Labrador has not really been legally explored at all. That may change following the university’s and the RNC’s actions.

Heidi Matthews is a law professor at Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto. Originally from St. John’s, they’ve been a vocal critic of the university’s response to the occupation. Matthews says the recent case of a court injunction in Toronto may have given Memorial a false sense of security in escalating its response to the student protest.

“Instead of proceeding in a more conciliatory or productive fashion, the administration was clearly emboldened by the University of Toronto injunction decision last week,” Matthews says.

That decision came about after Toronto police refused to enforce U of T’s trespass order against students. So the university had to pursue an injunction in court. When it was granted, students there opted to remove the encampment themselves. Memorial’s July 5 statement referenced this decision in warning student protestors to leave. But Matthews says it’s incorrect for the university to assert that the situations are identical.

“To basically almost wholeheartedly rely on the authority of an extra-jurisdictional lower court decision is a tactic for intimidating the students,” Matthews says. “To me it feels manipulative, because there’s no law school at Memorial, the general population doesn’t have the specialized legal knowledge that they would need to understand the intricacies of the law, and so when MUN just says that it was established that private property rights mean that we can kick out protestors, that’s not actually necessarily true.”

Matthews says the university’s actions could open it up to a Charter challenge, which might finally establish how the Charter and protest rights apply in this province and at this university. But they say Memorial’s apparent disregard for Charter rights in this matter is troubling.

“It’s one thing for the university to talk about private property, but they don’t talk about the Charter or constitutional rights around protest and assembly at all,” they say. “That’s really disappointing and politically and legally problematic.”

Universities public or private property?

“It’s an open and unresolved question,” says Matthews. “Universities are complicated because they’re both public and private for different purposes.”

They said the situation is particularly complicated in the case of Memorial. The Memorial University Act grants considerable powers to the lieutenant-governor, both from a property and a governance perspective. Government appoints most of the members of the university’s Board of Regents, and government funds the university in a variety of ways. Post-secondary education is a provincial jurisdiction, and each province has a different framework governing the relationship between its universities and the provincial government. Newfoundland and Labrador’s structure is very different from that of Ontario’s, meaning that an Ontario precedent may not be as relevant in this province as Memorial’s administration believes.

There are also other legal precedents at odds with the decision rendered over U of T. Higher-level court precedents in Alberta, for instance, have been seen as strengthening Charter protections on university campuses.

“It’s never been litigated [in Newfoundland and Labrador] and we don’t actually know whether the university has the extremely robust private property rights that it is asserting in this particular case,” says Matthews.

Anaïs Bussières McNicoll is a lawyer and Director of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association’s (CCLA) Fundamental Freedoms Program. The CCLA has also spoken out in support of students’ rights to protest on campuses, including through mechanisms like occupations and encampments.

“Our position is that university campuses are highly public spaces that have a particular commitment to free speech and freedom of assembly, and the essence of higher learning institutions that are universities requires free speech and free protest rights and freedom of association rights as well,” she told The Independent. “So in our view, whenever universities across Canada — especially publicly funded ones — are reflecting on how their campuses can be used by students, they should keep these very important rights and values which come from the Charter in mind.

“One should not forget that universities are intended to be forums for the exchange of ideas, criticism of the existing order and the betterment of our society,” McNicoll said. “One of the core purposes of university campuses is to allow students to discuss, defend and express their views on difficult topics. This includes the right to free speech, freedom of association, and freedom of assembly. Those are very important Charter rights and Charter values that universities should be mindful of when deciding how to address a certain situation.”

McNicoll also acknowledged the differing legal precedents around this issue, and the fact that how courts interpret this can vary from province to province. She emphasized that simply being disruptive is not sufficient cause for universities or police to infringe on Charter rights and shut down a protest.

“Protests in their essence often require an element of disruption. They need to be disruptive in some way in order to be efficient,” she said. “This is an important aspect of protest rights, and when universities are reflecting on what they can expect in the context of protests on their campuses, whether it be a march or an encampment or occupying a building for a certain amount of time, they should take into consideration the fact that the true fulfillment of freedom of peaceful assembly requires some degree of disruption.

“Free speech and protest are the very lifeblood of our democracy,” McNicoll continued. “As soon as we stop being able to speak our minds and go out in public space and online and explain why we agree or disagree with a certain circumstance, our society is no longer free and democratic as it should be.”

Student organizers dispute Memorial’s published statements regarding the occupation. While Memorial’s July 6 statement alleged that protesters had occupied the Arts building lobby “to the exclusion of others,” it was clear this was not the case. Reporters with The Independent observed university staff and students frequently coming and going through the lobby on a regular basis, and protestors appeared to have a cordial relationship with Campus Enforcement officers and Facilities Management staff working in the area.

The university’s July 6 statement also cited a fire department inspection report that identified concerns. Student organizers say the inspectors told them they had some recommendations which could be addressed by protestors to make the occupied area safer, and would provide those recommendations in a report to the university. Electronic communications provided to The Independent by student protestors indicate they made efforts to get a copy of that report from the university, along with a July 5 response from Memorial’s Director of Environmental Health and Safety Barb Battcock indicating she would be in touch to share the report’s recommendations with students the following week. Students also reached out directly to the fire department requesting a copy of the report, but say they were unable to reach anyone and their messages were not returned. The report was never provided to students to allow them to address the concerns, which they allege fire inspectors said were minor.

Students also made efforts to minimize the impact of their actions on employees in the building, they said. In advance of the July 5 protest marches through the building, they informed non-protesters in the area as well as campus enforcement officers of the duration of their three marches, and offered earplugs to those passing through the area.

Students say they made the efforts to ensure they remained within their Charter rights to protest and to respect the rights of employees working in the area. During the RNC action on July 5, Constable J. Walsh confirmed for The Independent there was no safety issue involved in the eviction of the students.

The Independent reached out to Memorial University for comment but did not receive a response by the time of publication.

Matthews is critical of the RNC response as well. When Memorial issued the trespass order and called in the police to enforce it, the RNC had a choice as to how to respond, she says. In the University of Toronto case, the Toronto Police Services refused to enforce the university’s trespass order against students, which is why the university had to go to court to pursue an injunction. Had RNC followed the Toronto police’s lead and refused to enforce the trespass order, Memorial would also have had to pursue an injunction, which would have allowed students to present their arguments as to why the court order shouldn’t be issued. Instead, RNC obeyed Memorial’s request and enforced the injunction without requiring any more robust legal process around the matter.

“The police didn’t have to charge anybody,” says Matthews. “That kind of policing is completely discretionary […] so it’s a failure on multiple levels.”

Students intend to continue pressuring the university, and say they have three key outstanding demands. They want to see the university’s Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and Anti-Racism (EDI-AR) office involved in all senior decision-making structures of the university.

Students also want the university to issue a statement acknowledging the gravity of the ongoing genocide and Israel’s culpability. Most importantly, students say, they want to see a robust commitment to disclosing Memorial’s indirect investments and a process for divestment from investments tied to weapons manufacturers or to Israel’s military occupation of Palestine.

In a July 5 statement that appears to allude to student demands for a statement that acknowledges the ongoing Israeli genocide, Memorial states that “university administration should not and will not take a political position that inhibits freedom of expression or academic freedom by directing staff, faculty members or students to conform to specific ideological viewpoints or limit their research, study or scholarship opportunities.”

Matthews, whose area of specialization includes war and international criminal law, says the university’s statements around neutrality “don’t hold together.” She notes the university regularly makes political commitments to aspirational human rights goals in its various strategic plans, such as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and other human rights principles, which she says are all examples of non-neutral positions similar to what students are demanding.

“Choosing not to invest in companies that are materially supporting international crimes doesn’t inhibit freedom of expression,” Matthews says. “Logically, it doesn’t flow; I don’t understand what they’re talking about.

“As an institution, if you’re going to ride the neutrality train right through a genocide, that’s not just morally and politically hugely problematic, but then you get into territory of actual participation and complicity in international crime,” Matthews explains.

“That’s really what the students are alleging — and I think they’re right — is that the university, by holding the investments that it does in these companies, is actively complicit not only in genocide but within widely accepted war crimes and crimes against humanity. There is really no question within the international legal community that multiple international criminal acts have been and continue to be committed on a daily basis by leaders of the state of Israel. That’s the legal reality that we’re in, internationally. We’re not just talking about vague human rights violations, we’re talking about the most serious of international crimes and we’re talking about material support for those crimes.

“Every day that the university continues to invest in these companies, its complicity in these crimes deepens. And for a university that is in a very difficult place reputationally already […] refusing to engage with students on a question of such basic civic morality is really shameful and it will cause further reputational harm to the institution.”