N.L. women face growing pregnancy risks due to climate change: study

New research looks at how global warming is impacting pregnancies

According to a new study, St. John’s is second to just one other Canadian city for the number of new days each year with heat levels that pose risks for residents who are pregnant. On average, the provincial capital now experiences 17 more of these hot days annually, second only to Charlottetown, P.E.I.

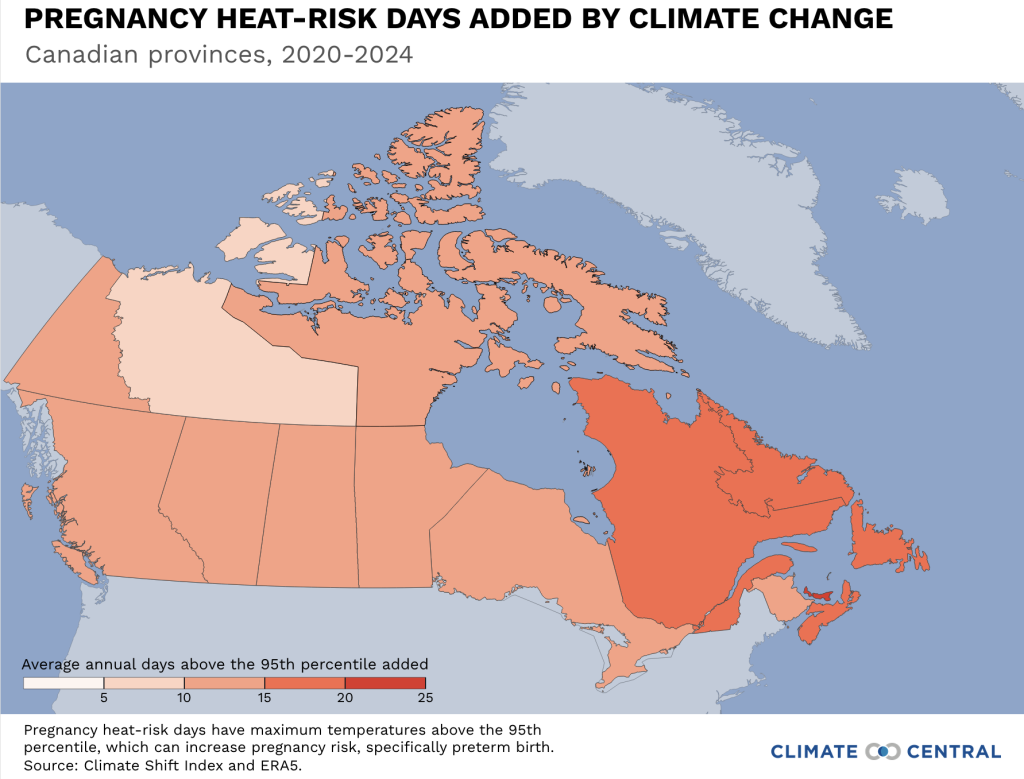

The report by Climate Central, a nonprofit news organization that focuses on climate science, also ranks Newfoundland and Labrador third among provinces and territories for the number of new “pregnancy heat-risk days,” which it defines as “days with temperatures warmer than 95% of temperatures observed at a given location.” Temperatures above the 95th percentile represent a level of heat the organization says can bring increased risk of premature birth. The organization’s analysis on heat and pregnancy risks evaluated data from 247 countries and territories worldwide between 2020 and 2024. Prince Edward Islands and Nova Scotia placed first and second for the number of additional pregnancy heat-risk days.

Exposure to extreme heat has been linked to health issues like high blood pressure, gestational diabetes, increased maternal hospitalizations, and other serious complications for pregnant people. It also raises the risk of stillbirth and preterm birth before 37 weeks of pregnancy.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

Dr. Itai Malkin, a public health physician and Newfoundland and Labrador medical officer of health, says the province defines heat risk as two consecutive days when temperatures are at or greater than 28 C and the intervening nighttime temperatures remain above 16 C or two consecutive days where temperatures are above 35 C regardless of nighttime temperatures.

Malkin says long stretches of hot days are a relatively new issue for the province, and as a result there aren’t enough cooling measures in place, such as cooling centres and accessible water fountains, to help people cope with the heat.

But as awareness grows and hot days increase in number and severity, the province is collecting data on how heat affects residents and is beginning to implement adaptation strategies. “We’re starting to think about how to monitor that and what to do about that.”

Maklin says the province’s hospitals track data on visits related to heat exposure. “There is, like, a code they put, and then that visit is added to a database, and it’s counted as a heat-related visit.”

Not just an urban issue

Dr. Bethany Ricker, 29, is a family physician and maternity provider in Nanaimo, British Columbia, where an additional 13 heat days have been added due to climate change. B.C. has been at the forefront of extreme heat events in Canada, including the 2021 heat wave that razed the community of Lytton and resulted in 619 deaths province-wide. She’s not surprised by the results; living and working in a much hotter province, she sees firsthand how heat-related complications affect her pregnant patients and their newborns. “When someone is pregnant, they are more medically complicated, and your body is not able to manage changes in the environment,” she says.

Ricker says heat can have an even more harmful impact on pregnant people in rural and Indigenous communities, where women and newborns often have fewer options to escape the heat because of limited access to cooling centres and hospitals. “On Northern Vancouver Island, there are patients who have to travel many hours—even more than a day—by ferry, by plane, to reach their closest medical center.”

Climate change is causing rapid warming in Newfoundland and Labrador. The summer of 2023 was the hottest ever recorded in the province, while St. John’s saw its warmest summer ever in 2024. Labrador is warming faster than any other part of the province. According to the provincial government, the northern region is expected to see winter temperatures rise by seven per cent by 2050. This could shorten the winter season by four to five weeks, which would have a major impact on transportation in the area.

Malkin says he is concerned about heat effects in Labrador. “We are trying to understand better where the gaps are. And yes, we hope to, as a next step, identify opportunities to mitigate it.”

Even though temperatures don’t often reach 28-35 C in Labrador, the Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of Canada. The increasingly warming weather and melting ice are impacting the culture and livelihoods of Inuit, including through disruptions to transportation and hunting.

Inuit communities have reported growing stress, anxiety, and declining mental health as climate change disrupts traditional practices central to their way of life. Limited access to transportation and health services further compounds these challenges and can result in delayed access to care. In Northern Labrador, for example, pregnant women must temporarily relocate to larger centres with maternity and labour health services, such as Happy Valley–Goose Bay, to give birth.

In 2024, the Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada, an Inuit women’s coalition, released a report highlighting the issues families face when pregnant women have to relocate, and called for an increase in midwifery services to help Inuit women give birth at home. The report notes that Inuit women often give birth “without enough support from family and friends,” adding that families can feel “unnecessary emotional and financial stress.”

Strategies

While there are several measures pregnant women can take to mitigate the potential health impacts of hot days—like cool baths, staying hydrated, visiting cooling centres, or staying with family members who have air conditioning—Ricker says climate change is a public health crisis and governments must do more to slow the impacts of a rapidly-heating world.

Climate Central’s findings are another example of why global warming needs to be taken seriously, she says. “We need to move away from our dependence on fossil fuels, which is causing climate change, and we need to build up energy systems in Canada that support a transition to green energy.”

Kristina Dahl, the vice president for science at Climate Central, says governments need to act on several levels to protect pregnant women and their newborns — first by swiftly cutting carbon emissions. Second, by raising public awareness about the health risks of extreme heat. And thirdly, by developing policies to help people adapt to rising temperatures. “Perhaps there are programs to help people pay their utility bills while they’re pregnant and potentially exposed to extreme heat, so that they can run their air conditioning at home,” she says, citing one example.

Dahl says climate change and its effects on pregnant people should be a concern to all: “We are all here on this planet because someone, at some point, was pregnant.”