Only Province in the Dark: Inside N.L.’s broken ethics system

The NDP has vowed to overhaul the conflict-of-interest disclosure system if the party forms government

Every Canadian province has readily-available public disclosures, a transparency resource commonly used by journalists and the public to monitor politicians’ potential conflicts of interest — except Newfoundland and Labrador.

The Independent spent over a year working to acquire the Members of the House of Assembly (MHA) disclosures. In every other province, without exception, disclosures are readily available online to every single member of the public. In this province, no disclosures are posted online and there are significant barriers to accessing them since access is at the discretion of the commissioner for legislative standards and typically requires visiting the office in St. John’s.

Newfoundland and Labrador’s laws around disclosures were last amended in 2001, before the internet became the cultural and communications force it is now. The federal government first adopted online publication of its conflict of interest declarations in 2006, and updated them nine times since then with the intention of modernizing the availability and use of the conflict of interest disclosures.

Ontario was the first province to start using an online database, but all provinces have made an effort to ensure information is available online. The most recent, Manitoba, made its conflict-of-interest disclosures available online in 2023. Making conflict-of-interest disclosures publicly available online is a form of accountability, encouraging civic participation and allowing residents and journalists to research their elected officials.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

When The Independent spoke with Newfoundland and Labrador Acting Commissioner for Legislative Standards Ann Chafe, there seemed to be resistance to making the disclosures available online. “There’s a line between privacy and what the public should know,” Chafe said in a phone interview last April. “Once you put anything online, it’s out there forever.”

Provincial law gives the commissioner control over what information is publicly shared. The law does not guarantee public access to information, leaving journalists and residents with limited recourse. This is entirely legal and rooted in a system that hasn’t been updated to reflect modern realities, such as the development of the internet as a source of accessible information.

Chafe was appointed acting commissioner in December 2022 after former commissioner Bruce Chaulk’s controversial six-year term ended. “Go and read the legislation. The legislation talks about how the public disclosure statements will be held; I have [them] here in a book,” Chafe during the phone interview.

The legislation mandates disclosure but hasn’t been adequately updated since its initial publication in 1995. The only way to ensure access is to visit in person and request to view the documents. With the information being more difficult to gather, compared to other provinces, journalists or residents may not understand all of the possible conflicts of interest in the House of Assembly.

The purpose of the disclosures is to serve as a mechanism within the government that aims to keep MHAs accountable. “The point of having these disclosures is me,” Chafe explained. “If they don’t satisfy my standards, I report them to the speaker, and the speaker chooses how he approaches it.”

Chafe has never reported an MHA to the speaker, saying that all disclosures have met her standards. However, she is an interim in the position, having come out of retirement to fill in the role while the Liberal government seeks a new commissioner.

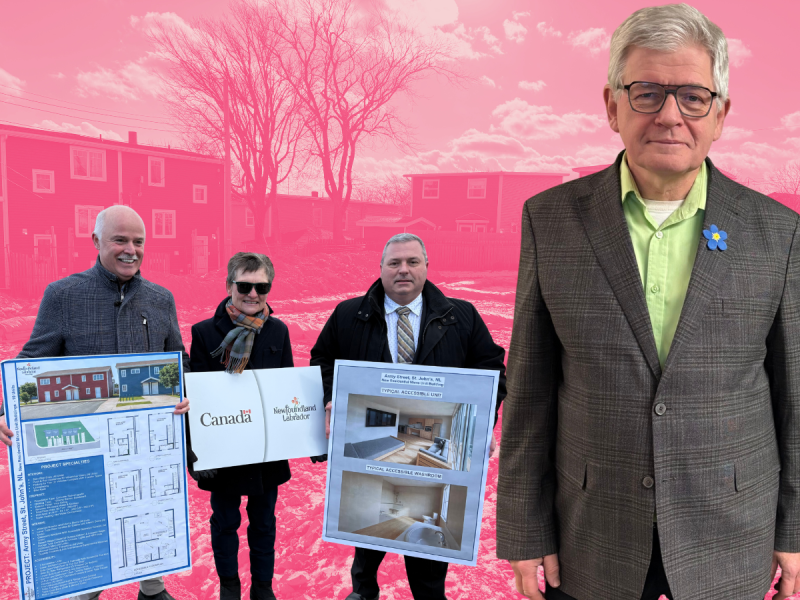

Newfoundland and Labrador NDP leader Jim Dinn believes the lack of transparency is tied to poor governance. “There are plenty of examples of a lack of transparency, yet we were made to believe that everything was in order,” he says. “This is problematic, especially in terms of good governance and keeping the government accountable.”

Earlier this month, and ahead of the province’s Oct. 14 election, Dinn announced that an NDP government would “be the most transparent government in the history of this province,” beginning with “publishing all MHA conflict-of-interest disclosure reports [online] so that they’re fully accessible to the public.”

Standing in front of the Commissioner for Legislative Standards’ office in a part of St. John’s far from downtown and nowhere near the province’s legislature, Dinn noted that those who want to see their MHAs’ disclosures have to “make an appointment” and visit the office “out in the middle of nowhere.” He also pointed out that people are “not allowed to make a copy” of the disclosure documents, and that “you’ve got to take handwritten notes, so there’s no way for anyone else to verify that what you’ve taken down is accurate.

“It’s opaque in many ways,” he continued, adding proper public access to MHAs’ disclosures is “important to having trust in our democratic system and making sure that politicians, including me—we’re not [acting] in our own self-interests.”

Investments kept private

When asked to disclose the declared assets of all MHAs, Chafe refused.

She believes MHAs generally don’t pay attention to their investments and often will let an investor manage their portfolios for them. Most of them, Chafe said, hand over management of their investments and forget they exist. “They’re not savvy with the day-to-day stuff — they’re too busy to pay attention. There’s only a couple that actually do the investing themselves.”

Regardless of politicians’ personal experiences with investments and how much they’re paying attention, Democracy Watch co-founder Duff Conacher believes these investments will, by default, cause a conflict of interest.

“The requirement should be that you have to sell your investments if you’re entering public office,” he says. Conacher advocates for laws which mandate the sale of all assets except for a family home and says blind trusts are ineffective because if MHAs are invested in developers, for example, there’s no incentive for them to vote for laws that benefit residents unless they divest their development holdings.

He calls blind trusts—or ‘screens’—a “sham facade,” because there’s “no way of removing financial conflict of interest” from land or assets. “All they do is hide financial investments,” Conacher says. An MP or MHA knows where and with whom they placed the blind trust and what investments are in it. “It’s easy to have a conversation on the back nine of a golf course with that trustee and at some point say, ‘Tell me what’s happening.’”

Newfoundland and Labrador’s laws don’t require MHAs to place assets in a trust. Federally, the prime minister and cabinet ministers are required to do so. In this province, the premier and cabinet ministers can continue trading as they see fit. Each province has its own rules around disclosures, four of which—Ontario, BC, Quebec and Alberta—require premiers and cabinet ministers to either divest or sell their investments or place them in a blind trust.

“There is one cabinet member who has assets in a trust, but that was her own decision,” said Chafe. The ethics commissioner can require MHAs to place assets in a trust but does not usually do so.

Transparency foundational to democracy

The Liberal government isn’t new to scandals. The province’s chief electoral officer was replaced after overseeing a “rocky” election in 2021. In 2022 the laws of the province were put to the test when independent MHA Eddie Joyce laughed at the commissioner for legislative standards for saying Joyce did not comply with the regulations. Joyce is, of course, still in office.

Public disclosures wouldn’t prevent these problems, but they would provide a resource to journalists and the public to point out errors of judgment and problems within the legislature. Transparency is not just a political virtue. It is a safeguard against corruption, a lifeline for accountability, and a foundational requirement for democracy.

“It’s not always an easy road to compliance, but I’m satisfied,” Chafe said, adding “the nature of this work should not be public humiliation of members or member’s spouses or their families. The nature of this work is to ensure the legislation is met, that the standards outlined there to avoid conflict of interest and full disclosure are met. So that is where my aim is.”

Does the public have a right to know what its leaders are invested in, or how elected officials might vote based on their investments? Conacher believes so and is critical of Newfoundland and Labrador’s current laws. “Financial conflicts of interest are the worst type,” he said. “They’re just below taking a bribe or a kickback, or diverting public money to yourself.”

He says financial conflicts of interest “lead to corruption, waste, and abuse of the public in other ways.”

Correction: A previous version of this story said Ann Chafe was also CEO of The Rooms. The Rooms CEO is in fact a different person, Anne Chafe, whose photo we erroneously ran with the original story. We sincerely regret the error.