Queerness, science, and the Mistaken Point fossils of Newfoundland

Art meets science in a unique Eastern Edge residency

How queer can Newfoundland’s 565-million-year-old fossils be?

That’s what David Nasca has come a long way to find out. He made the long drive from Chicago to St. John’s at the end of May (discovering along the way that the Argentia ferry doesn’t begin operating until June). He’s here for work, but unlike other scientists who come to study the unique pre-Cambrian fossil formation, he’s neither a paleontologist, geologist, nor evolutionary biologist.

He’s an artist.

Nasca’s month-long artistic residency with Eastern Edge Gallery in St. John’s will focus on the Mistaken Point fossil formation and what it contributes to the growing field of queer ecology.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

When science meets queer theory

Queer ecology is a burgeoning field, located at the intersection of scientific disciplines with gender studies and queer theory. The field is hard to sum up in a few words. It’s been shaped in part by efforts to challenge colonialism and other restrictive paradigms in the environmental movement. Where traditional environmentalism might have framed the goal of saving the planet as preserving “untouched” wilderness for the pleasure and consumption of middle class white, heteronormative families, queer ecology reminds us that we must preserve the natural world because we are part of it, inseparable from a vibrant and complex living planet on whose sustained health we live or die. In this, it draws heavily from Indigenous and decolonizing methodologies, along with insights from queer theory.

But queer ecology shapes scientific disciplines, too. It has helped reveal and highlight the fundamental queerness of the natural world. Where Christian and other religious fanatics once denounced homosexuality as a “crime against nature,” queer ecology has revealed that nature is in fact far more gay and queer than anyone ever realized (in fact, many scientists did realize this, only their work was either self-censored or violently repressed over the intervening centuries).

Evidence of nature’s pervasive queerness is proliferating at an astonishing rate. It’s no longer just about gay penguins raising chicks together; gay sexuality has been revealed as ubiquitous in the animal world, from giraffes to bighorn sheep and from dolphins to gulls. The mangrove killifish is able to self-reproduce thanks to its having evolved an ‘ovotestis’ (which is found in various forms in other animals, including humans, as well); New Mexico whiptail lizards have developed extra chromosomes enabling them to self-reproduce (and have done away with males entirely, sticking to lesbian sex), while some creatures like the parrotfish (as well as various types of frogs and toads) transition from male to female under various circumstances. Research is revealing that some species (white throated sparrows, sunfish, and more) may have more than two sexes, underscoring the inadequacy of the simplistic male-female binary (some mushrooms have evolved tens of thousands of sexes).

In the plant world, numerous species have been shown to encompass both female and male structures within the same plant (also enabling self-reproduction), while some transition between female and male at various points in their lives, or even different times of the day. This has led some botanists to adopt the position that applying animal-centred notions of sex and reproduction to plants simply doesn’t work.

This research is fascinating in itself, but it also has implications beyond biology and botany. Unsettling traditional ideas about sex and gender means we also need to reconsider all the social norms and conventions we’ve built upon those flawed paradigms. This too is an important part of the work queer ecology does, acknowledging humans as part of the same ecological systems that require unsettling and reevaluating.

“Queer ecology means a lot of different things to a lot of different people,” reflects Nasca. “We think of science as being very empirical and based on facts, but especially when it comes to biology so much of that is really arbitrary. We think about taxonomy and the way we divide a species with this binomial nomenclature and you would think it’s something that should be really easy for scientists to do. But actually these things are far from settled — they’re very contested, they’re constantly getting reread.

“One way for scientists to look at these things [like classifying species] is to ask: ‘how do we do this?’ But then there’s also the question of, ‘Why do we do this?’ What does it mean that this is really difficult to do? And I think that’s where a queer perspective comes in.”

The drive to classify things, including people, into neat, rigid categories has persisted into the present and permeated areas of life far beyond scientific research. It’s reflected in the strange obsessions dominating legislatures around the globe over what to do with a world in which gender and sexual identities suddenly appear to be proliferating wildly in a way that transcends the rigid binaries formerly—and erroneously—relied upon. What does this mean for bathroom access, passports, sporting? The shortcomings of a world designed for binary genders have become starkly apparent now that it’s becoming clear that binary sexes and genders are a myth, a mistake rooted in historical and cultural biases. The response of some to this conundrum is to embrace a more accurate, inclusive and expansive understanding of the world; for others, it’s a desperate and often violent effort to cling to the debunked binary paradigms of the past.

“There really is this drive to categorize,” reflects Nasca. “But also, why does it matter? Why was gay marriage even a thing? If two adults want to say, ‘we’re living together and pooling our resources and combining our lives in some way,’ why was that such a big deal? A lot of it feels like inertia — inertia from the attitude of, ‘Well, this is just the way it is.’ And I think we need to be questioning that.”

The fossil record as a queer archive

A visual artist and professor of ceramics at College of DuPage in Illinois, Nasca began incorporating a queer ecological vantage into his work eight years ago, and in 2022 attended a queer ecology-themed residency at the Banff Centre. His specific interest lies in invertebrate fossils, particularly from the period of the Cambrian Explosion, a period which began about 540-million years ago and witnessed a sudden tremendous diversification in the forms of life on Earth. That’s when the diversity of animal life really began to take off, eventually begetting everything from dinosaurs to primates. Nasca is both intrigued at the dramatically experimental forms animal life began to take at that time, as well as questions around why some forms of life have persisted to the present and others have not. Because the fossil record only offers snapshots of prehistoric life from periods spanning millions of years, piecing together what happened and why is a challenging, ongoing process.

“It got me thinking about how the fossil record is an incomplete archive, kind of like a queer archive,” Nasca explained. “We don’t really get a full picture.”

Queer historians and archivists face the same challenge: reading between the lines of historical documents, dealing with gaps caused by book burnings and destroyed archival records, interpreting euphemisms and carefully-disguised observations from periods of oppression.

What unites these disciplines—from queer archival work, to art-making, to the ‘hard’ sciences like biology or paleontology—is that they require imagination, thinking outside the box. There’s an interesting contradiction here in that the hard sciences are often considered data-driven and empirical. But data is no good without the imagination and creativity to interpret what data means in the real world.

“Whether you’re a modern historian looking back at queer history or a paleontologist or biologist looking back at past life, you need to do a lot of filling in the blanks yourself,” Nasca explains. “There needs to be a kind of openness in thought and in being willing to explore crazy ideas.”

It’s here that one begins to grasp the importance of art to science. Insofar as art is a creatively-driven discipline, artists are often able to make the intuitive leaps necessary to bring data to life—and to frame the questions scientists ought to be asking—in a way that data-immersed scientists might sometimes miss.

“This is why these two disciplines should be talking to each other,” Nasca says. “When you think about the most impactful science, the most paradigm-shifting scientific revelations are usually coming from somebody thinking outside of what was already known, and developing a new way of thinking about something. I think that’s similar to the way artists think. That’s why I love working and talking with scientists; I think there’s a really natural connection between scientists and artists. They’re both using different kinds of creative thought.

“This has been really interesting for me, coming from the contemporary art world. I try to be beholden to the science, but also I want my freedom to make my own interpretations. I’m looking at these Ediacaran animals that are still not super well known, and it’s like, what colour were they? Well, any colour that I want, because we really have no idea! This work requires creative skills and visual reasoning skills because the fossil record itself is incomplete, and then each individual fossil is also an incomplete record of an individual. So there’s a lot of interpretation and visual interpretation that needs to happen to start to make sense of this stuff.”

Interpreting Mistaken Point

It was while he was studying fossils at the Banff Centre that Nasca developed an interest in the Mistaken Point fossils of Newfoundland.

“What’s so interesting about the fossil material in Newfoundland at Mistaken Point is that this is before the Cambrian Explosion – these were some of the earliest multicellular forms of life. Some scientists have said that we don’t even know if these were animals, really. Can we really call them animals? We don’t know if they’re related to any kind of living species or if they were some other kind of experiment that life took, which then just sort of died out. I think that’s really fascinating.”

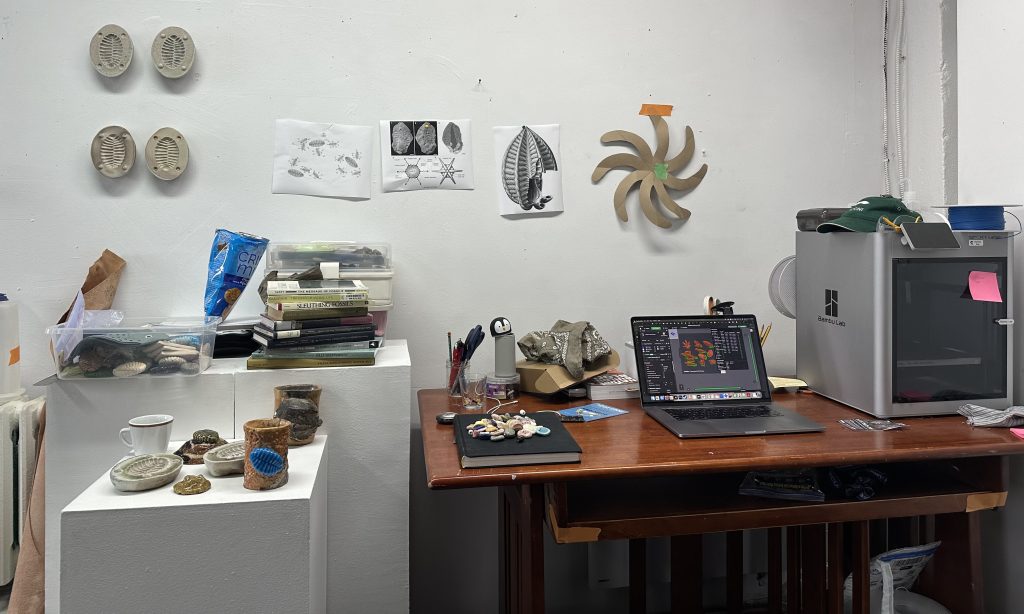

Nasca will be spending time at Mistaken Point, as well as other fossil sites along the Bonavista Peninsula and elsewhere. He’ll also be working with a team of paleontologists from Memorial University who are investigating new fossil sites. He’ll complement that with work at his studio at Eastern Edge Gallery, where he will be doing digital sculpting and 3-D printing, clay-making and ceramic sculpture. Lately he’s been experimenting with a material called Egyptian Paste, an ancient ceramic material that self-glazes. There’s a striking parallel, he finds, between the work of sculpting and the natural processes that produce fossils.

“Fossils are such interesting material to work with, because there’s a direct analogue to the mould-making and casting I do in my work,” he reflected. “I’m making a mould and casting something into it, and there’s this flipping back and forth between the mould and the cast. What is the actual creature, and what is the record of the creature? I’m exploring that kind of stuff too.”

“The standard narrative of evolution that we’re taught in schools is a kind of survival-of-the-fittest, focused on who survives to reproduce and what are the best traits to pass on,” he observes. “And while that is all at play, there’s also a lot more to it. What really interests me is the position of queerness in evolution.”

There is a parallel, we both reflect, between the diversity of life that manifested in the Cambrian explosion, and the diversity of identities that proliferate in today’s world.

“There’s been an explosion of queer diversity as well,” Nasca says. “You used to be just gay or bi or trans or queer, but now there’s hundreds of different identities. Which is good, but where are the points where we all come together, where are the points where we converge? Do we need a taxonomy of that too? There are all these new descriptors – AMAB, AFAB, queer, et cetera – and it’s helpful for people, but what would it be like if we didn’t do that? It’s kind of like a Cambrian explosion of diversity.

“That’s something I’m thinking about a lot with the Mistaken Point fossils and these super-early creatures. This was a time in the history of life in which there wasn’t really predation or competition in the ways that we think of now. The classic Cambrian animal is the trilobite — so these were all very soft-bodied organisms. That’s a term that comes up a lot in paleontology that I think is just beautiful to think of in relation to queerness and queer ecology, which is that even though we all have skeletons, we’re really all just soft bodies.

“So the Cambrian explosion is when you started to see kind of a split in evolution where you have predator animals who are developing essentially weapons—almost like an arms race—and prey animals that are developing different kinds of armour and defenses. So I’ve been thinking about and exploring that idea in relation to queer community and mutual-aid networks—and socialism and Marxist thought too—thinking about this group of animals from a slightly more political point of view.

“I’m also just very interested in looking at different animals, invertebrates, and thinking about what kind of metaphors from queerness we can draw out from those animals — animals that change their genders throughout the life-cycle, or have the ability to reproduce asexually and sexually.”

Queerness, science, and the diversity of life

The insights and discoveries queer ecology has brought to evolutionary and biological science underscore the broader importance that queerness brings to science.

“Within a medical context when it comes to our current understanding of sex and gender, it’s settled science at this point that it’s more complicated than just chromosomes,” Nasca says. “I don’t think that kind of understanding would have come about without queer people both working in science and outside of formal science, leading us to understand these things differently.”

The impact of queerness on science isn’t limited to research insights, however.

“Science suffers from a big communication problem, where it’s really hard to explain what’s going on in a way that feels relevant to people,” he says. “I think there’s a lot of potential for queer people and queerness to enter into the equation when it comes to science communication, which is such an important part of science. How can we present these ideas in a way that engages with people and introduces them to all this fascinating material that’s so rich to think about — and not just from a scientific perspective, but it’s also rich to think about in terms of how we think about ourselves.

“It’s important to have queer human histories taught in schools, but people should also be able to learn in children’s books about animals that change their gender, so they can understand that not only is this something that people have done, but animals do this too!”

Nasca sees his visual art as a form of science communication as well, reflecting new insights on fossils and provoking new questions and ideas about how they shape our understanding of life itself. He’ll be spending a month in St. John’s, exploring fossil sites and working at Eastern Edge Gallery, where he hopes to put off some workshops for the public as well. Following his residency, he plans to travel to Labrador before returning to his studio and teaching position in Chicago.

“Frankly, I make artwork because I love doing it,” he says, smiling with anticipation at the thought of the month to come. “But there’s so much out there that is worth knowing, and the more we can open up the narrative of what science is, and what it means to be engaged with the history of life, and the more diverse voices we can get in there doing that — it’s all so important. I think a lot about artwork as a pedagogical opportunity, about how this is my chance to teach something.”