Seismic shift needed to address N.L. housing crisis, experts say

Housing is a human right in Canada, yet unchecked rent hikes, Airbnb pressure, and landlord-lawmakers have left thousands in Newfoundland and Labrador one paycheck away from homelessness

“The economy and human rights aren’t mutually exclusive,” says Marie-Josée Houle, Canada’s federal housing advocate. “We’re not here to throw governments under the bus—but we can hold them to account.”

Houle worries that many governments have lost sight of the housing crisis, singularly obsessing over one thing; “The word is ‘the economy, the economy,’” she says. “You can have a healthy economy and still respect human rights.”

Newfoundland and Labrador’s housing crisis is in full swing: rents are soaring, the cost of living has become untenable for many, and both renters and homeowners struggle to afford basic needs. In 2019, Canada enshrined housing as a human right in the National Housing Strategy Act, giving Canadians a legal right to adequate housing: protection from forced eviction, access to essentials such as water, heat and sanitation, affordability, habitability, and freedom from discrimination.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

Yet those rights remain aspirational for many in Newfoundland and Labrador and the province’s Liberal government has been reluctant to acknowledge that housing is a human right.

The province has the highest home-ownership rate in Canada. In 2021, 75.7 per cent of residents owned a home, compared with the national average of 66.5 per cent. The remaining quarter of the population—renters—are left exposed, with little control over escalating housing costs and little representation in the House of Assembly. It makes sense then, that a large number of the province’s MHAs are landlords.

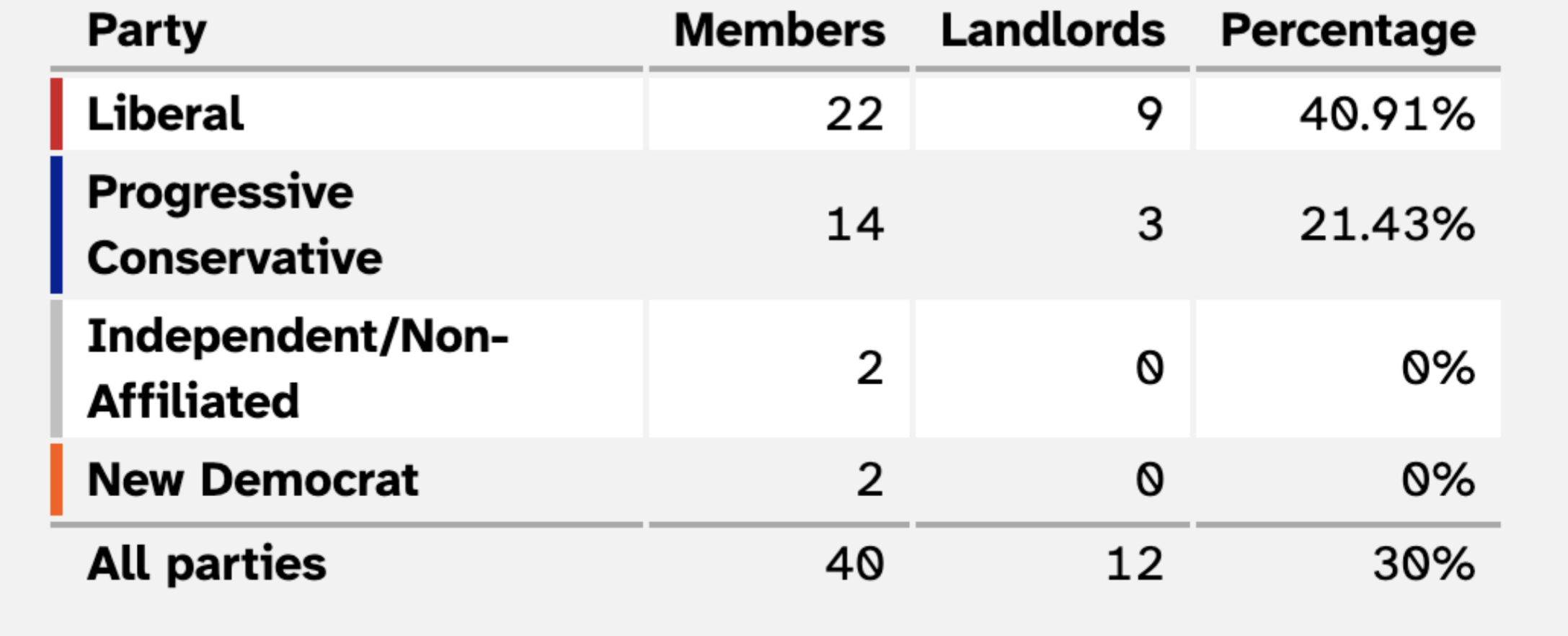

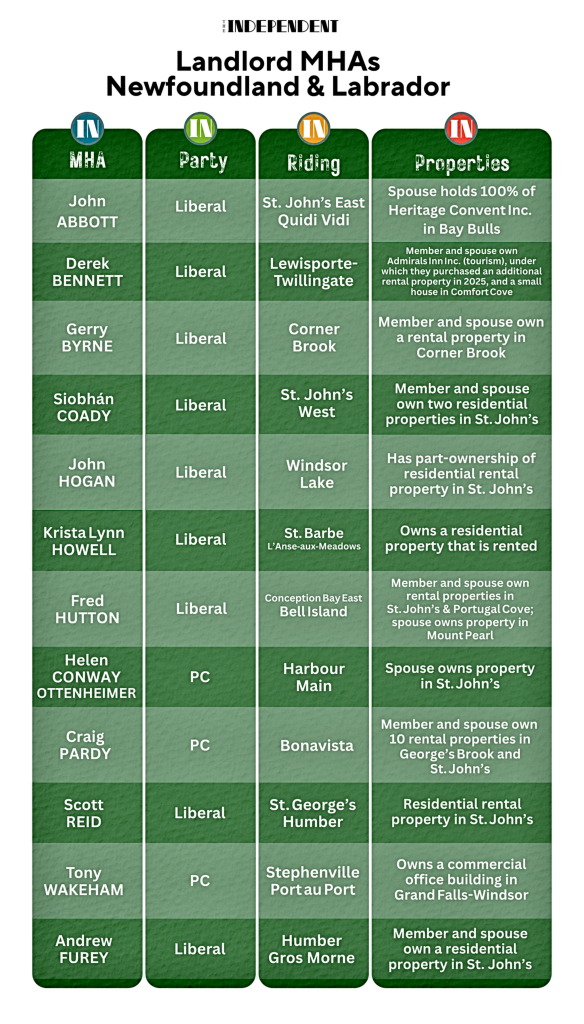

Twelve out of 40 MHAs elected to the House of Assembly in 2021 were landlords, a higher percentage than most provinces and an unknown fact to most Newfoundlanders and Labradorians. Whether this is to blame for the Liberals’ underwhelming effort to address the housing crisis is not necessarily apparent, but it could be a contributing factor to actions not being taken in the province’s legislature in recent years.

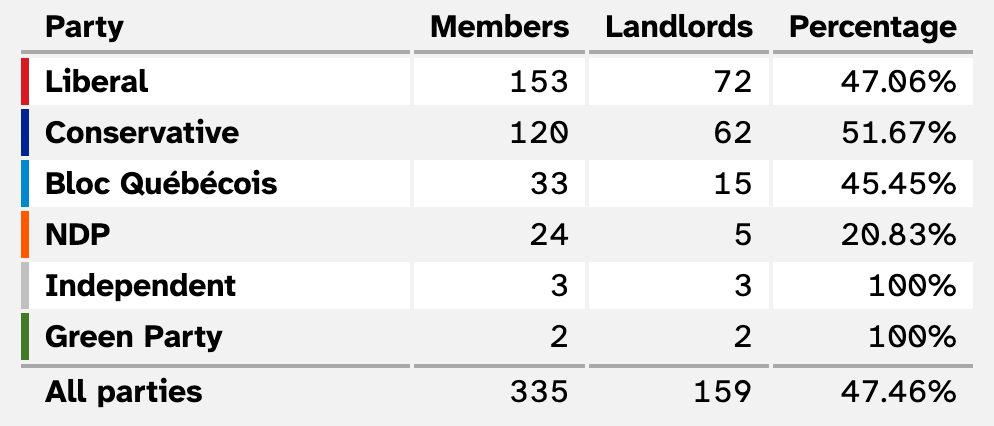

Across Canada, with the housing crisis burning hot, 47 per cent of all MPs elected to the House of Commons in 2021 were landlords, including St. John’s East MP and Liberal cabinet minister Joanne Thompson.

In the database, for an MHA to be considered a landlord, they or their spouse must receive any type of rental income. In addition to having the highest percentage of homeowners in Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador also has the highest percentage of landlords in public office among the provinces (PEI notwithstanding, where there are laws which change the data on this topic and make it hard to quantify.)

The below table includes every MHA elected since 2021 who reported to the Commissioner for Legislative Standards that they received, or their spouse received, rental income.

Rent control

Currently, little is being done to strengthen renter protections. Newfoundland and Labrador is one of a handful of provinces without rent-control legislation. Landlords can raise rents as much as they choose every 12 months with sufficient notice.

Sara Beyer, policy manager at the Canadian Centre for Housing Rights, says rent control laws help prevent skyrocketing rents and homelessness. “Rent control is such an important piece of the puzzle to address housing and the homelessness crisis that we’re facing across the country, and that is definitely manifesting in Newfoundland and Labrador,” she says. “If you’re getting a 50 per cent rent increase, your income probably isn’t going up by 50 per cent.” Beyer calls this phenomenon “economic eviction,” when rental prices being raised with no limits pushes someone out of their home.

The Independent previously reported that a young mother staying at the Tent City for Change homeless encampment in St. John’s said she was forced to give up custody of her baby after a landlord raised her rent beyond what she could afford.

Listen to the Tent City for Change episode of The Independent’s Lock & Key podcast series:

Without safety nets, many more people are now homeless. Visible homelessness in the province has grown, particularly in St. John’s, but tent encampments have popped up in other places around the province.

Doug Pawson, executive director at End Homelessness St. John’s, said the COVID-19 pandemic was a turning point. “For a lot of folks experiencing homelessness, they’ve been squeezed out of the housing market,” he said. Pre-pandemic, there was ample amounts of available housing in St. Johns, hitting nearly 7 per cent. “Now it’s hovering just around 1 per cent.”

Between 2018 and 2024, homelessness in Canada increased by 20 per cent, according to the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. Newfoundland and Labrador has been no exception in this regard.

Pawson explained short-term rental platforms like Airbnb have removed a significant share of the housing stock, tightening the province’s long-term rental market. The number of Airbnb units skyrocketed during the pandemic as people spent their vacation times in Canada, and often wanted to escape cities while working remotely.

Services stretched thin

Homelessness services across the country are stretched thin. Operating costs are high and frontline staff are struggling to keep pace. “It’s a heavy job supporting folks who are experiencing homelessness. We see a lot of turnover, a lot of burnout,” Pawson said, adding “there aren’t enough resources for the people coming through, and it takes a toll when you can’t see an end to the issues you face every day.”

Even those who do manage to secure affordable housing often endure substandard conditions. “There is a whole market of individuals who buy up properties and house the people nobody else wants to house,” Marie-Josée Houle explains. Many tenants, she says, are kept “in absolute derelict conditions,” a clear violation of Canadian and UN human-rights standards. That includes Newfoundland and Labrador’s older housing stock, which often fails to meet basic habitability requirements.

For decades, Canadian governments have touted home purchases as the safest, best investment that will secure people’s money for retirement. When it comes to this crisis, Houle points to those who are benefiting most: realtors, mortgage brokers and banks. “No wonder we’re being pushed into a mortgage again.” Houle says people were being pushed to constantly invest anew while being promised there would be no risk. To believe that there were no consequences to investing money in the market is simply untrue. “They’re being lied to,” she says.

Houle stresses a basic need like housing doesn’t need to be designed for profit. “If someone is willing to get into that business [of being a landlord] and is entitled to not having any risk at all—well, that’s not capitalism. Capitalism includes risk.”

In his book The Tenant Class, Ricardo Tranjan, a researcher for the Canadian Center for Policy Alternatives, says the housing market is working as it was designed. It was always made exclusively with the focus on capital growth, disregarding the basic need for habitation. This disregard for those people wanting to rent or own a home with no intentions to sell it has led to both tenants and homeowners suffering.

Those who want to renovate their homes are often unable to, with renovation prices skyrocketing and people using their home equity to fund it. The average expenditure of home renovations has doubled since 2019, leaving many single-house landlords with tenants living in the same building as themselves, unable to repair problems with their rental unit unless they charge significantly more rent. Either the owner has to eat the costs with no guarantee of return, or the renter could be forced out through an economic eviction.

So far, the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador has not taken significant steps to regulate the problem, as the province has fallen way behind in home building.

Models for how to implement laws are readily available for the province to study. Prince Edward Island has some of the strongest rent control laws in the country, and Quebec historically had some of the lowest rental prices in Canada. Recently, Quebec has taken further measures to decrease the amount rent can be raised and there is an ongoing moratorium on certain types of evictions in the province until vacancy rates reach 3 per cent.

Elizabeth Schwartz, an assistant professor at Memorial University and director at The Hub for the Study of Local Governance in Newfoundland and Labrador, sees several challenges for both implementing stronger laws as well as large building projects.

“Half the population lives across the province outside of the metro area of St. John’s,” she says. This is uncommon, since nearly three-in-four people across the country living in urban centres. The province’s unique makeup needs to be addressed, instead of copying and pasting the same concepts used in provinces with greater urban populations, such as densification and zoning law reform. Other major impediments need to be addressed too, such as properties being used for short term getaways, or rent control laws being implemented.

“It’s not helpful if what we’re doing is creating tons of sprawl and exacerbating everybody’s budgetary issues,” Schwartz says, explaining that without access to public transit, and supermarkets or other necessities, maintaining roads and public infrastructure in large areas will become a major constraint on the province’s budget. She also emphasizes the difficulty of implementing large-scale solutions in Newfoundland and Labrador based on the number of people who work in government. “This bureaucracy is quite small in terms of policy analysts,” she says. “We need more people thinking about these problems and not just mimicking what’s happening in other places.”

Houle believes there is a problem coordinating across governments. “This lack of coordination between governments has been a huge challenge,” she says. The federal government promised to invest more than $25 billion over several years in various aspects of the housing crisis, but the money came without adequate oversight. “This is where the federal government can take leadership,” Houle says. “I think the federal government needs to be a lot more dynamic with what they want those funds to do and where they should go.”

Last spring federal Housing Minister Gregor Robertson said he doesn’t want housing prices to go down, he only wants housing stock to go up. Last month, the Carney government announced an investment of $13 billion into the rapid expansion of housing construction via its Build Canada Homes agency.

N.L. election promises

Now in the midst of a provincial election campaign, Newfoundland and Labrador’s three major parties are promising to confront the housing crisis. The Liberals have reiterated their promise to build more housing but are relying on private, for-profit interests to handle the bulk of new housing, a commonly used tactic with both Liberal and Conservative governments across the country. It uses taxpayer funds reinvested in private corporations to expedite market growth, and often results in significantly higher costs and more bureaucracy than a centralized system.

In a campaign stop in Labrador last month, PC leader Tony Wakeham promised a Progressive Conservative government would work with communities “to help create affordable and independent housing for seniors who prefer to move into a community environment.”

The NDP, meanwhile, has committed to adopting a housing-first approach and to “treating housing as a human right and ending the cycle of homelessness.” The party says it will launch a program called NL Homes, through which it would build 1,000 “public, affordable housing units” across the province annually. It would also “assign unused provincial land to municipalities, housing co-ops and community groups ready to build the affordable housing needed in their communities – removing the red tape and empowering local communities to be part of the solution,” the party’s costed platform reads. These types of innovations are widely accepted by researchers and experts as the most effective way to build a long term and sustainable housing market. It is also common for governments to make ambitious announcements for housing construction or social housing targets, only to fall short.