St. John’s Pride and Trans marches evoke history of struggle

This year’s theme, ‘No going back’, can’t be understated in today’s political climate

“No Going Back” was a fitting theme for St. John’s Pride Week this summer, given the ongoing social and political backslide to a more violent, less enlightened era.

The refusal to regress is at once a dedication and an affirmation that says: we will not return to an era when landlords refused to rent to queer couples, when palliative care units turned away people with HIV and cemeteries refused to bury them, when schools were not permitted to deliver sexual health education and when children had so few rights and so little bodily autonomy they could be sexually abused by Catholic clergy while government officials and media looked the other way.

Yet, this is the inevitable outcome of the policies being pushed by right-wing and conservative politicians in Canada and the U.S.

Halting such a widespread regression seems daunting, but to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past we can start by reflecting on how we got to our present.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

In this year’s Pride Month feature, The Independent weaves together reflections on local queer history with snapshots of our proud present. More than 5,000 people marched under blazing skies in the July 20 Pride Parade, and hundreds braved the pouring rain for the Trans March on July 26. As they marched up New Gower Street and Duckworth Street, or sloshed along Water Street, those vibrantly-coloured, boisterously-chanting crowds passed iconic sites of local queer history.

This article combines Tania Heath’s powerful photography of these two marches, with historical snapshots and reflections curated by Rhea Rollmann, drawing on material from her book A Queer History of Newfoundland. It’s our hope the piece causes you to reflect on our shared queer past, and on the whys and hows of not going back to a time when ignorance and callous intolerance devastated the lives of generations of Newfoundlanders and Labradorians.

St. John’s City Hall

In recent years, St. John’s City Hall has been the launch point for Pride parades, where thousands gather, donning makeup, adorning their costumes, building up their floats, dancing in anticipation, and gathering in formation to march. Participation now numbers in the thousands. Floats have grown to include flatbed trucks carrying entire bands, motorized boats, accessibility buses, roller-skating drag queens and derby teams, and dancing furries, to name a few. The parade commences with the firing of an airhorn, wending its way past thousands of spectators along New Gower Street, onto Duckworth Street, winding back onto Military Road, and concluding with a party in Bannerman Park.

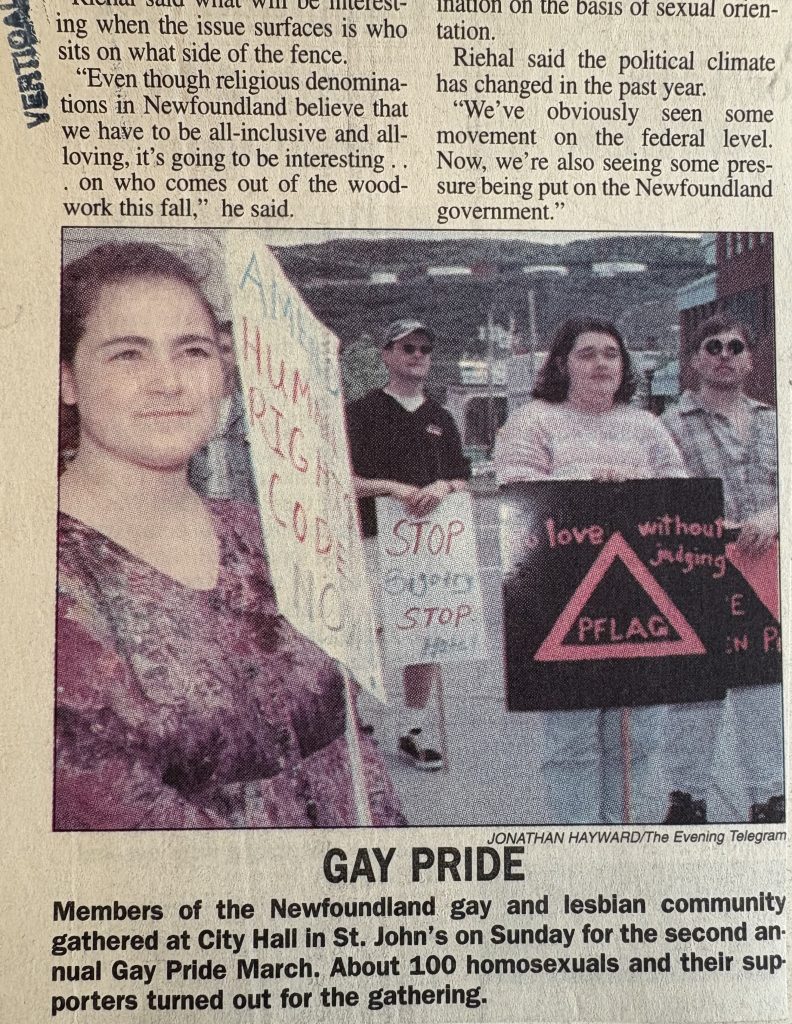

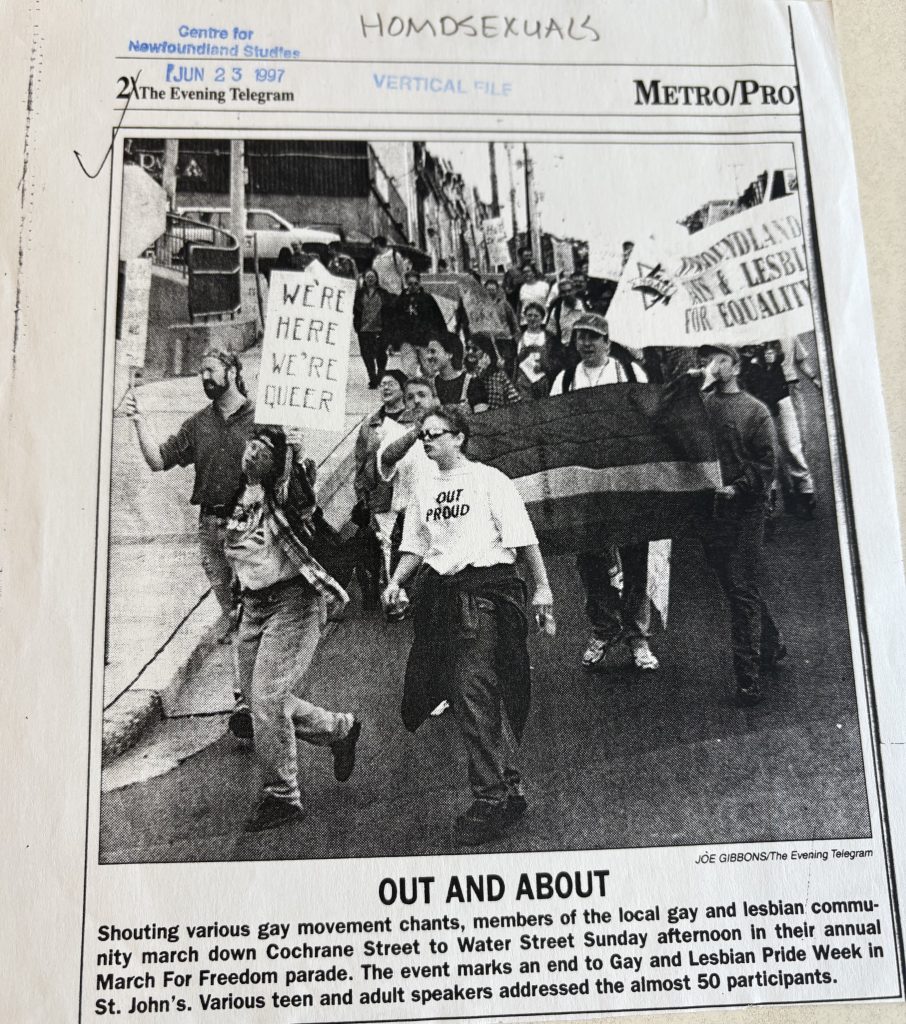

In the 1990s, when the first St. John’s Pride parades began—then called ‘March For Freedom’—City Hall was the launch point. The less jubilant, more politically charged events began with a rally and speeches, often to crowds of just a few dozen. Organizers from that era recall mixed feelings as they looked out at spectators and recognized members of the queer community there, masquerading as curious straight onlookers, present in spirit but afraid to step forward and out themselves.

It was in 1991 when Gays And Lesbians Together (GALT) — a fiery, militant local activist group inspired by the direct action tactics of radical queer groups like ACT UP and AIDS Action Now — asked St. John’s City Council to recognize Pride Week in the capital. There were no human rights protections for 2SLGBTQ+ people in the province at the time, and discrimination, especially in housing and employment, was rampant. But then-Mayor Shannie Duff, who had already marched in Pride parades in New York City in support of her gay son, brought the proposal to council. It was strongly endorsed, including by openly lesbian councillor and feminist activist Wendy Williams. St. John’s became one of the first cities in Canada to recognize Pride Week, the same year it was first officially recognized in Toronto.

LSPU Hall

The parade passes the LSPU Hall, situated between Duckworth Street and Gower Street, which, in addition to its broader iconic past, is strongly rooted in queer history. In 1981, the Hall housed the founding meeting of the Gay Association In Newfoundland (GAIN), the province’s 1980s-era queer rights organization. GAIN played an important role at a time when the province’s other human rights groups still kept a wary distance from queer organizers.

In the early ‘80s GAIN organized Pride festivals similar to, but smaller than, the ones we see today, without marches or official recognition. The organization also played a key role in the AIDS crisis which gripped Newfoundland and Labrador in the ‘80s, and this eventually came to consume the bulk of its activism by the later part of the decade. By the mid-’80s GAIN’s steady, patient activism finally brought community partners like the Newfoundland and Labrador Human Rights Association into the struggle for queer rights. Its role in organizing social events for members, at a time when some venues still refused to rent space to queer groups, cannot be understated.

As an arts space, the LSPU Hall also played a vital role in exposing the community to queer theatre, art and music. The queer work of artists like Robert Chafe, Maxim Mazumder, Bernadette Stapleton, Cathy Jones, Jacob Chaos and others all helped normalize queer themes, lives and experiences at a time when politicians continued to dodge the topic of gay rights. The Hall also didn’t hesitate to let its space be used for political purposes. Activist groups like GALT and the St. John’s Status of Women Council held press conferences, rallies and media gatherings there, denouncing government intransigence on queer rights or defending local publications from censorship attacks. The arts have always played a vital role in social change, and the Hall’s close links to the queer community offered important supports at a time when broader community solidarity still remained a scarce resource.

Solomon’s Lane

Solomon’s Lane and the adjoining block of buildings on Water Street have important connections to queer history. In the late 1980s and early ‘90s, 156 Water St. was known as Solomon’s; it was the city’s premiere gay dance club. In 1993, as patron Brian Nolan was leaving the club, he was accosted, harassed (including the use of homophobic slurs) and wrongfully arrested by four Royal Newfoundland Constabulary (RNC) officers. He was delivered to the penitentiary, where he experienced further harassment from prison guards. Nolan, also a union activist, charged the provincial police force with discrimination and spent two years fighting for justice (his initial complaints were dismissed by the RNC). In a case which eventually wound up at the NL Supreme Court, he finally prevailed and the court ‘read in’ sexual orientation protections for the first time in provincial history, putting pressure on the government to update its Human Rights Code to include the prohibition of discrimination based on sexual orientation. That was finally achieved in 1997. Gender identity protections for trans people were later added to the Code in 2011.

The building at 164 Water St. — today home to Spirit Bar — has been the site of various gay bars for many years, including Kibizers, the Alley Pub and the New Alley Pub. It was at the latter venue that ‘Hot, Horny and Healthy’, a safe sex workshop for men who have sex with men, was held during the first official Pride Week in 1991 (a similar workshop for women, ‘Lick Latex and Live’, was held concurrently at the St. John’s Women’s Centre.

Queer children and youth

These days children are often used in transphobic and anti-drag rhetoric by right-wing, conservative politicians, much like children were used in homophobic rhetoric 20 or 30 years ago and earlier. Right-wing activists pursue policies that expand censorship and reduce children’s bodily autonomy rights, claiming their bigotry is about protecting children. As activists have noted, the irony is that it is actually the homophobes and transphobes who are harming children by exploiting them for political gain and by depriving them of the education that would keep them safe.

In the 1990s many gay rights groups, including Newfoundland Gay and Lesbians for Equality (NGALE), struggled with the growing ranks of queer youth demanding to be part of their movement. Many older activists were afraid to allow youth to be part of queer organizations, lest they face false but nonetheless painful accusations of child abuse. Queer activists like Mikiki, a member of Youth For Social Justice, recall the tense debates NGALE had in the mid-1990s before eventually allowing them to join as a youth rep. As Mikiki pointed out, refusing to allow youth participation in community organizations, and refusing to provide sexual and gender education to youth, in fact put the province’s youth at greater risk.

In the ‘90s, queer and feminist activists drew attention to the ways stigma around queer identities, and a lack of publicly accessible education around gender and sexuality, created a repressive and anti-youth-rights environment which led to the sexual abuse of generations of youth at the hands of Christian clergy at Mount Cashel Orphanage and elsewhere, a tragedy covered up for years with the complicity of the RNC, the provincial government and local media. Queer teachers and educators like Ann Shortall, Susan Rose and others fought hard for change within the education system as well. Activists then and now have pointed out that censorship and repression, such as those pursued by right-wing governments in Saskatchewan and Alberta today, puts youth at greater risk of harm than education and transparency.

St. John’s Status of Women Council

As the Pride Parade turns off Military Road to enter Bannerman Park, just out of camera range can be seen 83 Military Rd., the former location of the St. John’s Status of Women Council (SJSWC) Women’s Centre.

Since the 1980s, the SJSWC has played an important role in supporting queer rights groups, providing training, resources and meeting space for a succession of queer organizations. Many of the province’s leading feminist activists were queer as well, but that didn’t stop the SJSWC from having painful internal debates over inclusivity, often pitting upper-class straight white women against poor and working-class queer and lesbian women. One such conflict led to the brief closure of the Centre in the early 1990s, and spurred the creation of a stand-alone lesbian organization: Newfoundland Amazon Network (NAN). NAN played a vital role in the fight for human rights protections for queer people, and trained and supported NGALE activists when that organization launched a couple of years later. NAN and NGALE jointly organized some of the province’s earliest Pride parades. Since those years, SJSWC has worked hard to be inclusive of sexual and gender minorities, and to prioritize its commitments to these and other marginalized communities.

AIDS/HIV crisis

The AIDS crisis gripped Newfoundland and Labrador in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but the situation was exacerbated in this province by the church-run K-12 education system (the Christian churches also held outsized influence over provincial health care institutions). Church interference in education and safe-sex campaigns contributed to the deaths of hundreds – likely thousands – of Newfoundlanders and Labradorians. For many years the provincial government also refused to address the AIDS crisis, until its spread through the heterosexual population also reached crisis levels. This tragic period has been evoked in recent years by Palestinian solidarity activists, who have drawn on protest tactics honed by AIDS activists in the ‘80s and ‘90s to bring attention to a crisis in which Palestinian lives have been treated as expendable by our governments, much the same way the lives of gay and bisexual men living with HIV were treated as expendable 30 to 40 years ago.

A similar point has also been raised by safer drug supply advocates: all of these movements draw on the lessons of harm reduction and direct action in fighting for a society that treats everyone with dignity and respect – whether queer, Palestinian, a person who uses drugs, or any other group. Intersectional solidarity has become a hallmark of queer and trans activism, and this principle led St. John’s Pride to be one of the first Pride festivals in the country to embrace Palestinian solidarity (along with boycott and divestment principles and the banning of police/security uniforms from Pride) in 2024.

Learning from history

The lessons of our queer history are important for all Newfoundlanders and Labradorians to become familiar with. If we are to build on the foundation of decades of powerful queer activism and the accomplishments of generations of queer activists, it’s critical to be familiar with this history and with the mistakes made by our government and institutions in the past, and the policies and practices that were introduced to avoid those same mistakes in the future.

The policies targeted by right-wing and conservative activists today didn’t arise out of a vacuum; they were a direct response to the tragedies of the past. Knowing and understanding that past, and honouring it as we march through the streets of our communities today, where visible evidence of queer history stands all around us, can be a source of pride and an inspiration for all the important work that remains to be done.