Labrador still without air quality sensors well into 2025 wildfire season

Province cites same issues it faced installing federally-funded sensors in 2024

For a second straight year, the provincial government has failed to install a network of federally-funded air quality sensors throughout Labrador which have the ability to provide real time local air quality data — a vital service during wildfire seasons that could help mitigate negative human health impacts on Indigenous communities and potentially save lives.

Last fall The Independent published an investigation into the provincial government’s failure to install the Purple Air sensors throughout Labrador despite having the equipment and ample time to get the network up and running as it did on the Island, and as other provinces and territories have in recent years.

But weeks after fires raged outside Churchill Falls last month and smoke inundated communities across Labrador, the provincial department of health and NL Health Services still have not figured out how to install the sensors and keep them running. As of June 16, just two sensors are monitoring air quality throughout Labrador, in Labrador City and Nain.

The department of health told The Independent Friday that three devices were installed since late 2024, in Nain, Natuashish and St. Lewis. “However, the St. Lewis and Natuashish sensors are temporarily offline,” a spokesperson said in an emailed statement from the department. “We continue to troubleshoot with NL Health Services and Health Canada.” The department also says the installation of the other devices “has been delayed due to ongoing connectivity issues in the region and availability of personnel to complete installation and establish Wi-Fi connectivity.”

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

The Independent’s September 2024 investigation revealed the province faced the same barriers—connectivity and staffing—last year, raising questions about whether the Liberals are doing enough to protect Innu, Inuit and all Labrador residents from the harmful effects of wildfire smoke.

Torngat Mountains MHA Lela Evans, who represents several Inuit and one Innu community in the provincial legislature, says she’s “really worried” the air quality in Labrador isn’t being monitored to the extent it should be. With a background in biology and experience in the field in Labrador, Evans is aware of the significant health risks posed by the particulate matter in wildfire smoke. “We see a lot of the elders, and survivors of TB, and people with COPD — they suffer,” she says. “And this group is just as vulnerable as they were to COVID when everyone was so worried about if COVID gets into our communities.

“Now, when we look at the fire and its really fine particulates, it does create a lot of problems.”

Evans believes the government isn’t as motivated to spend the money to install the sensors, because “if we get into it, these elevated readings […] then alerts and advisories would have to go out and people would be knowledgeable. And then you’d have to look at, are we going to evacuate? Are we going to move the elderly and the people with health issues?”

Last year, Dr. Itai Malkin, a public health physician and the medical officer of health for the provincial government, told The Independent doctors are concerned about particulate matter in wildfire smoke, which “has a lot of evidence for some negative health outcomes. So if an individual breathes these particles, they go deep into our lungs, and they can cause irritation and inflammation.” According to Health Canada, wildfire smoke “can travel in plumes in the atmosphere up to several thousand kilometres,” and that exposure to the smoke “is associated with an increase in all-cause mortality as well as exacerbations of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and increased respiratory infections.”

In 2022 the federal government estimated wildfire smoke resulted in 620 to 2,700 deaths each year from 2013 to 2018. Indigenous people face higher rates of respiratory illnesses like asthma and bronchitis, raising the urgency of local air quality monitoring in Labrador.

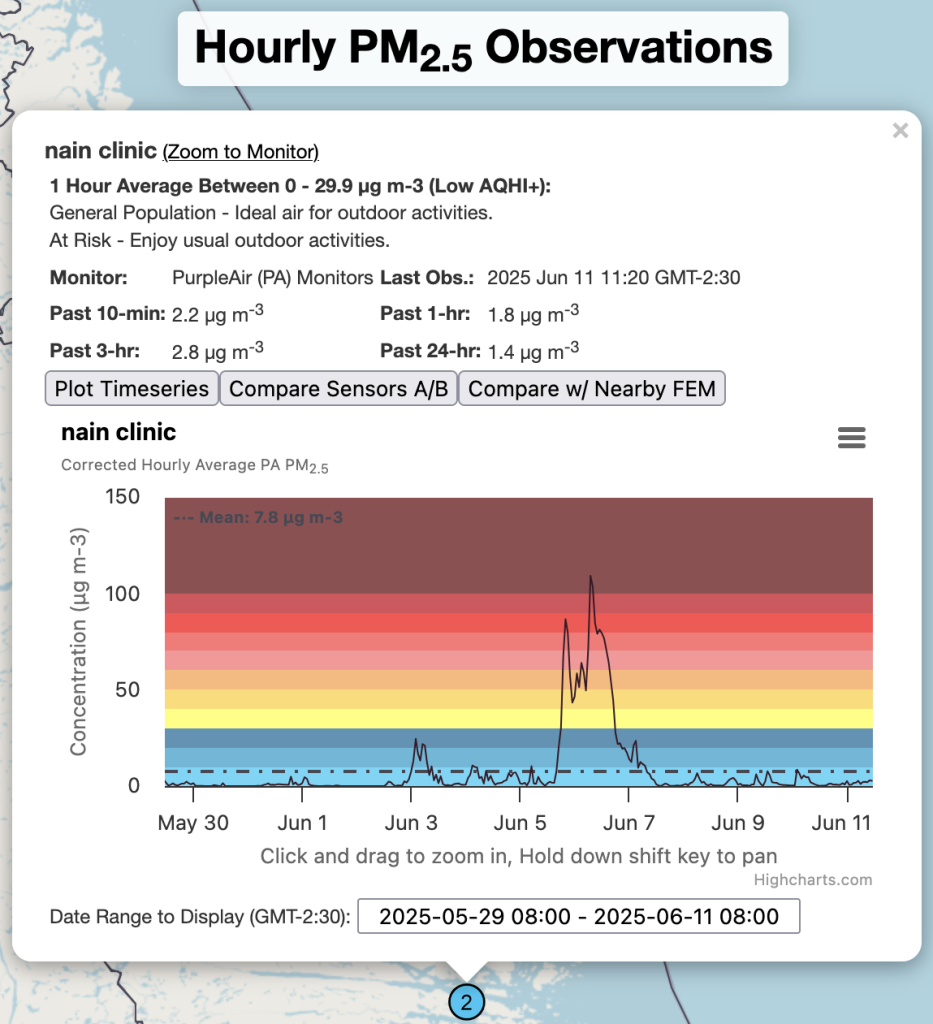

Late last month wildfires burned just outside of Churchill Falls, prompting the town and its residents to prepare for evacuation. While an evacuation wasn’t necessary, smoke from those and other fires in Quebec and elsewhere has impacted air quality in communities throughout Labrador. In Nain, where one of just two air quality sensors are presently operating, data shows that air quality levels were high enough on June 6 to warrant the reduction or rescheduling of outdoor activities, according to the Canadian Air Quality Health index. Data from others locations where the province has installed sensors in Labrador, like Happy Valley-Goose Bay, St. Lewis, and Natuashish, are unavailable since those sensors are offline.

Despite the government’s alleged challenges installing air sensors in Labrador, similar and identical ones are active throughout Canada’s north, including in Quebec, Nunavut, Northwest Territories and Yukon.