Province misses opportunity to reimagine public transportation in climate action plan

Transportation accounts for 44 per cent of Newfoundland and Labrador’s greenhouse gas emissions

All it takes is a drive up Kenmount Road to understand how car-dependent a society Newfoundland and Labrador is, even in its capital city. Beyond the traffic congestion is the way one of St. John’s main thoroughfares is packed with car dealerships hawking their wares and touting their interest rates to get prospective buyers through the door.

In some ways, it’s understandable that Newfoundlanders and Labradorians would need their own vehicles. We live in a large province for our relatively small population, and that means regularly traversing great distances for work, to see people we care about, or to buy the things we need.

But that state of affairs comes with drawbacks. Vehicles are expensive, and have only become more so since the pandemic and the decision of many automakers to ditch some of their more affordable models, if not the option of sedans altogether. Plus, there’s the cost of fuel, insurance, maintenance, and everything else that comes with car ownership — not to mention the infrastructure we collectively pay to maintain.

These days, the average selling price of a new car in Canada is over $66,000, and those buying used vehicles aren’t even getting the kind of savings they once expected. On that side of things, buyers can expect to pay an average of nearly $36,000. All told, the average Canadian shells out about $1,370 a month to cover the costs of their vehicle — which is far too much money for many among us.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

Given 88.5 per cent of commuters in the province last year said they got to work by driving—one of the highest percentages in the country—and we buy more new vehicles than anyone else, this is a serious issue for a lot of people. It’s also why I was disappointed to see the paucity of imagination in the government’s new Climate Change Mitigation Plan when it comes to something as serious as how we all get around.

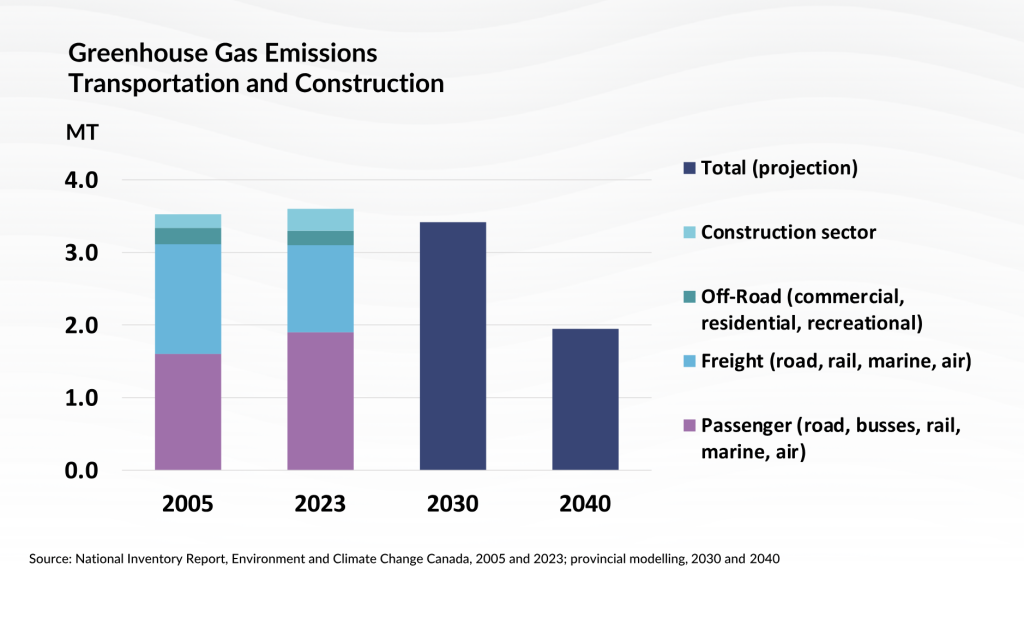

The plan lays out how the province aims to tackle our greenhouse gas emissions over the next five years so we can meet our goals of a 30 per cent reduction by 2030, while setting ourselves up for a 60 per cent drop by 2040. Transportation accounts for a full 44 per cent of those emissions, with passenger transportation making up 23.5 per cent when separated from commercial and freight.

That’s a big number to tackle, so you’d imagine the government has some ambitious, and maybe even creative, ideas for how to reduce transport emissions while improving mobility options for Newfoundlanders and Labradorians. Sadly, that’s not what readers will find in the plan.

Aside from some acknowledgements of public transit, the plan is primarily focused on electric vehicles and charging infrastructure. On the public side, the province currently has 33 fast chargers—with 11 ultrafast charging stations to be installed this year—to serve about 1,700 battery-powered vehicles. Given the push to electrify the vehicle fleet and the percentage of people in our province who drive, it makes sense to highlight what’s being done to promote the transition — but it’s not nearly enough.

Even if we’re to take the focus on electric vehicles at face value, the provincial government’s efforts to encourage adoption are failing. By the end of 2024, the EV market share in Newfoundland and Labrador was a mere 2.8 per cent—the lowest in the country—even as the national average exceeded 12 per cent, and nearly a third of vehicles in neighbouring Quebec were electric. That certainly means there’s opportunity to improve, but it also means the province doesn’t seem to have much vision for improving our communities or how we get around them.

When public transit was a priority

Newfoundland and Labrador is a province that ripped up the train tracks that once crossed the island, leaving residents with no good alternative to traverse this vast land. Our capital city also had streetcars for 48 years, before they were ripped out too. Some of them even had wait times of less than 10 minutes for passengers.

We gave them up because the car was believed to be the future, and the train and streetcar were the past. But now that many of us are stuck in traffic and paying an arm and leg for our vehicles, more people would like an alternative if the government would bother to invest in services that properly deliver for their riders. Indeed, we already see that.

In St. John’s, Metrobus has seen a boom in ridership in recent years, with 58 per cent more riders last year than before the pandemic — quite a feat when many transit agencies across North America are struggling to return to pre-Covid levels. Investments have been made to buy more electric and hybrid buses, but that was to allow some diesel buses to retire instead of solely to expand the fleet, and a new express route was launched at the beginning of the year.

But the service still has a lot of drawbacks. As The Independent previously reported, and many riders will know, clearing bus stops and sidewalks in the winter remains a problem. Buses can also be unreliable, whether it’s because they’re not on time or because riders have to wait far too long for the next bus to arrive. It’s not all the fault of Metrobus; it’s also the result of our governments’ lack of interest in providing public transportation strong enough to be a viable option for people in the province’s cities and larger towns.

Beyond electric vehicles

The Climate Change Mitigation Plan mentions that the provincial government has given some money to Metrobus, and to a bus service in Happy Valley-Goose Bay. But if it was serious about reducing transport emissions and giving people reliable alternatives to driving, it would be doing far more.

Instead of simply providing occasional capital funding for infrastructure or new buses, it should step in and pay a hefty share of transit operating funds — the money needed for the day-to-day running of the service. City governments have been demanding support on operating budgets from the federal and provincial governments for some time. If the province stepped in to cover half of Metrobus’s operating expenses, it would have more funds to improve its service. The same deal should be offered to other communities.

The province could think even bigger. It could propose regionalizing Metrobus with a bigger budget and a mandate to provide better service in Mount Pearl, Paradise, Conception Bay South, and surrounding communities to make it easier to get around the Northeast Avalon. Beyond that, it should do more to promote the benefits of getting around with a bike, including by improving bike lanes and safe bike parking. It could support other forms of active transportation such as walking and wheeling by contributing to trail and sidewalk snow removal in larger centres. It could also get serious about rolling out a public, reliable intercity bus service that would serve locals and tourists alike.

Those proposals are just the tip of the iceberg. The province has brought in 20,000 new residents over the past few years, and it clearly would like to keep them. We have emissions targets to meet, but in the process we can also think about how we improve our communities. Making it easier to get around is a key part of doing that.

For the past half century, we’ve focused on forcing people into cars while saddling them with a big bill — not just for their own cars, but for the infrastructure they require as well. It’s long past time our government breaks out of that narrow mindset and recognizes a modern Newfoundland and Labrador needs more than roads, highways, and cars — even if they do eventually get electrified.