The business case for public transit in St. John’s

Expanding public transit in the St. John’s Metro region may seem unrealistic, but when you look at the facts and figures, it’s both reasonable and doable

Most of us see public transit in St. John’s as a burden on taxpayers, a service no one would use except people with no other options. There is some truth to the tax claim since the City of St. John’s funds transit infrastructure and bus purchases and provides an annual operational subsidy to Metrobus, amounting to $14.9 million in 2024.

Meanwhile, funding limitations and poor service mean that the bus service is indeed used mainly by those who don’t have access to a car. Metrobus is required to operate within a fixed budget and the public doesn’t see the value in increased funding. What would the benefits be?

Public transit benefits are directly proportional to the percentage of the population that uses it. Currently only a very small percentage of the overall population of St. John’s takes the bus regularly, which means the benefit to the overall population is also small. Average passenger rides per day in 2024 were around 13,000. The City’s latest collision report indicates annual average daily vehicle traffic is around 773,158 at the 32 busiest intersections. A crude calculation based on these figures suggests that bus passengers in St. John’s make up less than 2 per cent of the traffic. Province-wide, in 2016, around 2.5 per cent of people use public transit, compared to 14.7 per cent in Ontario and 13.3 per cent in British Columbia, according to Statistics Canada.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Studies show that more frequent, better connected service leads to significant increases in people choosing to take the bus. Good public transit has social benefits and it’s good for business. The question is how to convince drivers to switch.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

Cost benefits of high-quality transit

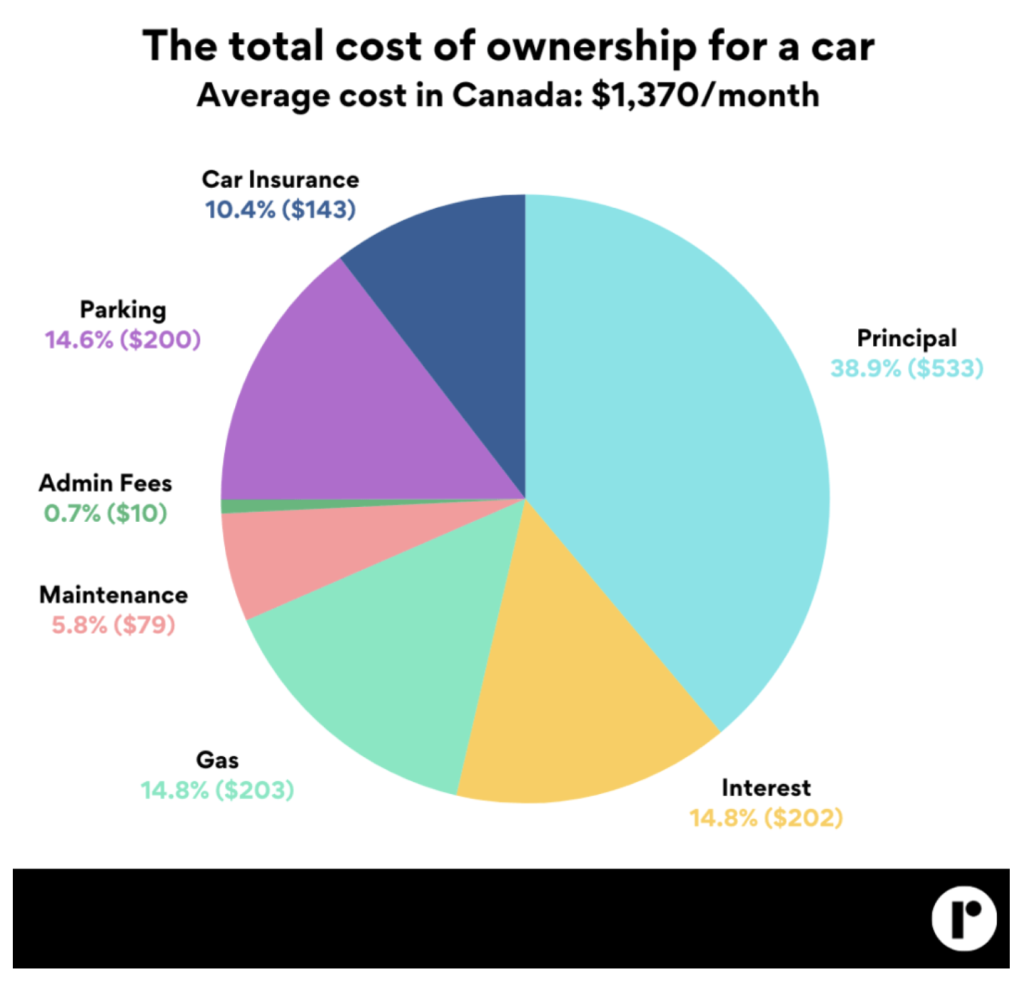

St. John’s is a very car-orientated city but we are at a critical time in history where this can change. The cost of living has increased to unattainable levels for younger generations. A high-quality transit network—relatively fast, convenient, comfortable, and integrated with the community—can help. Amid rising automobile and gas prices, Ratehub.ca estimates the average monthly cost of car ownership in Canada is approximately $1,370 — or $16,440 annually. Even if people choose to own a car, commuting by transit can still save up to $5,000 a year for parking and fuel.

Having one vehicle rather than two could free up enough finances to enable a young family to buy a home. Some inner-city residents own a car just to travel occasionally to destinations outside the city. Extending transit could result in many of these residents no longer needing a car at all. Many travellers prefer high-quality transit even if it takes longer than driving because they can work, study or rest while they travel. In this way, high-quality transit can also lead to higher productivity.

If enough people use it, high-quality transit can help reduce traffic problems such as congestion, collisions and pollution emissions. According to the City of St. John’s, the capital has 1,780 lane-km of roads and, between 2018 and 2022, an average of 1,313 collisions per year. According to a 2017 study from Alberta, vehicle collision costs at the time could range from $14,000 to $225,000. Reducing collisions by just 5 per cent through reducing congestion could result in savings of over $900,000 annually for the insurance industry and far more for emergency services. Reducing congestion on highways would have even higher-cost benefits since these accidents tend to be much more severe. These savings alone could fund expanded transit service. Advantages regarding emissions are harder to quantify in terms of costs but still vital. High-quality transit reduces vehicle miles traveled, leading to lower emissions and improved air quality.

Expanded transit means less space needed for vehicles and infrastructure in both residential and commercial developments. This would bring more tax revenue to the City of St. John’s since more homes and businesses could be built in the additional space, thus raising the assessed value. It would also result in a reduced lifecycle cost for road maintenance and snow clearing, with potentially significant savings in arterial road and collector-street infrastructure. For example, based on my own calculations for Dewcor, if Southlands Boulevard were constructed as a two-lane road rather than a four-lane one, the cost of construction would be reduced by as much as $2 million per kilometre. This savings would also be seen in the corresponding lot price which would be approximately $3,000 less per lot. As a development incentive, the City could choose to charge the developer a transit fee in return for permitting a smaller road cross section or less parking. This would encourage more development and increase private funding for transit.

Health advantages are another aspect of financial benefits of high-quality transit. As the population ages, an increasing number of people won’t be able to drive due to health issues and fixed incomes. Tourists often expect to be able to experience the city without a car. Newcomers, many of whom are already heavy transit users, may find the poor state of public transit in St. John’s offputting and instead seek out a city in which it’s easier to get around.

High-quality transit will benefit all of these groups. Not only will they be able to get around freely but there are also significant population health benefits just from walking to and from bus stops. Studies have found that using public transit contributed to more than two hours of exercise per week, while health research has shown that even 15 minutes of exercise a day for someone who otherwise gets little or no exercise could increase their life expectancy by an average of three years. These health benefits would also result in substantial savings in healthcare for the province.

The cost of development

Our current development policies focus on road expansion. While this can reduce congestion and improve vehicle safety, it also tends to induce additional vehicle travel over time. This increases costs in downstream congestion, traffic risk, pollution, snowclearing and long-term road maintenance. These impacts should be considered when comparing roadway expansions with transit improvements. For example, traffic studies indicated that a two-lane Team Gushue Highway extension could meet current projected traffic volume, but the province decided to build four lanes to accommodate potential future growth at an additional cost, based on my own calculations, of approximately $8 million. If that amount had been provided to Metrobus for a transit upgrade, it could have provided long term environmental benefits and cost-of-living savings for residents as well as improvements in the overall efficiency and well-being of the city.

The province is currently planning a new highway connection from the Outer Ring Road to Kenmount Road for a new hospital; the cost would likely be in the tens of millions of dollars. This is an opportunity to perform a cost-benefit analysis for improved public transit versus another four-lane highway. The Town of Paradise is also considering building a new bypass road from St. Thomas Line to the Outer Ring Road. Meanwhile, current peak traffic between the CBS Bypass and Allendale Road is reaching or may have already exceeded the highway capacity. The province will need to add a third lane to this section of highway soon to maintain an acceptable level of service and safety. The estimated cost of doing so would be approximately $20 million, excluding any upgrades to overpasses. New arterial roads and highway lanes might not even be needed at all in some cases if the equivalent funding were directed to improving public transit.

High-quality transit also allows for the development of more compact neighbourhoods where residents tend to own fewer vehicles and drive less. This in turn enables homes to have smaller driveways, reducing standard lot frontage and bringing multiple lasting benefits for the municipality. Smaller driveways mean less stormwater runoff, less snow clearing and more space for snow storage in winter. For prospective homebuyers, this size reduction would reduce the cost of a building lot by up to $30,000 in the St. John’s area, in addition to the $3,000 savings noted above.

It’s human nature to take the path of less resistance and our government has been inadvertently facilitating a culture of individual car ownership through its development policies. Dealers in Newfoundland sell more cars per capita than any other province in the country. We must ask ourselves, why?

How do we convince people to take the bus?

Waiting is a major complaint with transit users worldwide and a key reason people choose driving over transit. Frequency should be at least every 20 minutes and ideally every 8-10 minutes for busier routes. Early morning frequency is especially important for workers to have dependable routes to work. Weekend frequency is also needed to support businesses, recreation, and shopping. To improve travel times, we need to consider more direct routes and more express routes. Riders should be able to travel anywhere in the city in 30 minutes. We need more buses on the road to make this happen.

Adding express routes from suburbs to downtown will help bring people back to the heart of the city and reduce vehicles on our arterial roads. We must also add express routes from suburbs to other business districts like Bristol Place, Memorial University, Pippy Place, Donovans Industrial Park and East White Hills. Transit hubs in suburbs will need parking lots for park-and-ride services. Transit hubs can be more than places where travellers arrive or depart. Facilities in and around them make the area a destination itself and can provide a ripple effect that encourages investment in the area, generates new revenue streams, and boosts wider prosperity.

Transit also needs to be regional. St. John’s has a small population relative to other major cities in Canada, so to increase ridership we need to increase the catchment area. At a minimum we should extend express routes to CBS, Torbay, Portugal Cove-St. Philips and Paradise. A study to determine the viability of expanding to Holyrood and the Southern Shore should also be in the long-term transit plan. New technology such as Autonomous Rapid Transit (train-bus hybrid, which can run on the road or designated lane) may help the viability of longer express routes into the city.

Another major obstacle for public transit in the St. John’s region is our weather. It’s difficult for users to consistently walk from their home to the bus stop, and waiting for a bus in the winter is uncomfortable. We can’t control the weather, but we can do things to help lessen the effect. Bus shelters are essential. Transit hubs with heated spaces are even more attractive. We need investment in more covered or enclosed connectivity in the downtown and university areas in particular. Where shelters and other enclosed spaces are not possible, real-time route updates will help people reduce wait times in the cold. Snow clearing sidewalks is also critical to allow safe walking to the bus stop.

In addition to improving frequency, expanding service and preparing for weather, there are two main ways to change driving culture: incentives and disincentives. Incentives like reduced fares have been shown to result in 10-50 per cent of the travelling public choosing transit over driving. However, disincentives such as higher parking fees or worsening traffic congestion can cause an even greater number (20-60 per cent) to shift to transit.

Despite slightly better results for disincentives overall, incentives are more likely to be popular with the public. We could start with pilot projects like running a five-day express route with free fares between Mount Pearl and downtown, then doing the same for Paradise and CBS. This incentive could be advertised through targeted media campaigns. Employer incentives combined with municipal tax incentives can also promote public transit use. For example, downtown employers could provide annual bus passes to employees rather than subsidizing parking. To encourage this practice, the municipality could give business tax credits to participating employers. This type of incentive can be expanded to households as well. There are also indirect incentives. For example, home values have been shown to increase in areas with good public transportation systems.

Disincentivizing vehicle use by allowing more traffic congestion to occur or reducing parking requirements for new developments would be much harder to approve politically. However, spending more money on transit rather than expanding arterial roads is a good start. Adding a dedicated bus lane and/or carpool lane would both speed up transit and make the alternative less appealing. Although increasing downtown parking fees would not be popular, the City could choose to increase them closer to transit hubs only and use the profit to help fund transit operations.

Where do we go from here?

To change people’s attitudes about riding Metrobus we also need a public campaign to make transit cool and convenient. Advertise that single occupant vehicle commutes are bad for the environment. Educate people on available real-time route updates and the Metrobus Mobile App. Let them know about new initiatives and incentives. We want to make people feel that having the best transit system in Atlantic Canada is something to be proud of. It will have lasting benefits, drawing more tourists, students and immigrants, supporting a healthier population and strengthening our economy.

The future of transportation is not individual car ownership. To increase rider participation, the region will need to invest significantly to build out the infrastructure, purchase buses and hire drivers. Improving transit must be prioritized. I estimate that forgoing future road infrastructure expansions alone could result in almost $40 million in savings, while adding 40 new express buses and associated transit hub facilities to serve suburban areas would cost under $40 million. The Federal Public Transit Infrastructure Fund would provide up to 60 per cent of this capital cost, bringing the investment for the region down to under $20 million. All other costs and social benefits suddenly become a bonus that could make the Greater St. John’s area one of the best places to live in Canada.