What would it mean to build a city for kids?

An interview with St. John’s active transportation advocate Ryan Green

Run an internet search on “bike safety for kids.” You’ll get a bunch of hits advising you to make sure bikes are sized correctly and in good working order. You’ll likely be advised to put kids in high-visibility clothing, fit out their bikes with lights, and teach them hand signals. Above all, you’ll be told, make them wear helmets.

When several elementary schools asked cycling advocate Ryan Green for safety demonstrations in early June, after a heartbreaking crash killed a seven-year-old who was biking in his St. John’s neighbourhood, Green’s mind first went to these “basic things” too.

“But,” as Green commented in a widely-shared June Facebook post, “something felt off about that, because it puts the responsibility on the kids, which is wrong. What I really want to tell them is the truth: Riding your bike is dangerous because of cars.”

Making Connections sat down with Green to talk about that post and related issues.

Will you stand with us?

Your support is essential to making journalism like this possible.

Green is a member of the City of St. John’s Sustainable and Active Mobility Committee and has held several positions on the volunteer board of Bicycle Newfoundland and Labrador (BNL), including Director of Community Transport and Advocacy. He is also a well-known advocate for active transportation and cycling for kids, coordinating a bike bus for students at Bishop Feild Elementary, where his own children attend school.

What follows are highlights from our conversation, edited for length and clarity, starting with his motivation for posting on Facebook:

It certainly wasn’t my intention to create a viral post. It was something that was building up, something I’ve been thinking about for a long time. Usually when I write about [active transportation], it contains a lot of technical information and lots of research. But this one was totally emotional. People were asking me to do bike safety demonstrations, and I felt like we’re just talking about this in the wrong way. What we’re telling kids is not wrong, but we’re not giving them the full picture. It reached a point where I just needed to get it out. I wrote it all in about 10 minutes.

A city built for drivers

When asked why he thought the post resonated so strongly, Green speculated that it had “hit a nerve,” particularly with people who remembered when kids “rode their bikes everywhere,” allowing them to get around without adult chauffeurs.

I get the sense that a lot of people know in their gut that the current system is not right […] and there’s probably a better way.

The current transportation system and urban planning approach is based on a series of choices over many decades. I’m not sure if people realize that, but I do think that people know that what we have right now, the status quo, is not great for certain groups: kids specifically.

[W]e’ve lost something in the last couple of decades. I think that’s why the post resonated with people of a certain age.

Green noted that although he had been involved in bike advocacy before having kids, becoming a parent gave him a different perspective on the effects of the urban environment:

When my kids got to the age when they were needing more independence or more freedom, that’s when I really started thinking about how our cities are built and how they affect the mobility of children and the way they experience where they live.

The physical benefits of active transportation, which builds exercise into everyday life, are obvious, but Green emphasized emerging evidence that independent mobility is good for kids’ entire beings (see here, here and here for recent studies).

There’s a lot of research coming out now about how childhood independence is really important and linked to lower levels of anxiety and depression in kids and teens. So, I think it’s important to have an emphasis on independence for kids, and the built environment is a big factor in that.

For Green, the way we build and organize our cities and towns is the crux of the difference between dominant approaches to bike safety — “wear a properly fitted helmet and bright clothing” — and the issues that should preoccupy us most. As he put it in his post, what he really wants to tell kids is “the truth”:

Riding your bike is dangerous because of cars.

Cars can and will kill you.

You live in a city built for cars.

Aspects of our towns that have become so taken-for-granted we don’t even notice them make activities that are inherently “a bit risky” outright dangerous, said Green, pointing to streets “designed so that cars can get around quickly and park easily.”

‘We need to differentiate real danger from risk’

Cycling is fantastic, especially for kids, in managing risk. It’s so important for kids to be able to learn about risk and manage it on their own.

We don’t see that many people getting seriously injured just riding their bike by themselves, even without a helmet. It’s the cars that make biking dangerous. […] That’s where the danger comes from, and that’s outside of people’s control. [When you are biking] you can’t control what a car is going to do.

As far as helmets go: I would never advocate against helmet use. Certainly, [there’s] lots of research showing how it reduces brain injuries. So, helmet use is great, but I think traditionally we’ve equated that with safety [when] the real [danger] is because of motor vehicles and not cycling itself. We see in European cities where cycling has taken hold and they have best-practice infrastructure in place, people don’t really wear helmets, and they have very low rates of injury.

In addition to purpose-built infrastructure, there is safety in numbers when people bike en masse rather than in isolation. This is the idea behind the Critical Mass rides held in St. John’s and other cities around the world every final Friday of the month. It’s also a feature of the bike bus:

When my daughter was in Grade 1, we started the bike bus at Bishop Feild Elementary. […] Every two weeks, kids and parents and teachers, school staff, all bike to school together in one big group. It’s super fun. Everyone absolutely loves it. I didn’t expect it to get as big as it got, but it’s been going strong for four years now, and we get huge turnouts. Lots of other schools are asking about it. It creates quite a spectacle on the street when you see 50 or 60 kids riding their bikes down Military Road in St. John’s. It’s fabulous!

We get a bit of a mix of reactions [from drivers]. Most people just have giant smiles on their faces and it’s like: “Wonderful thing to see at 8 o’clock in the morning.” You get an occasional irate driver who’s not very happy that they have to wait 90 seconds at a crosswalk. But I don’t feel too bad about that! There’s a slight subversive element to the bike bus, which I kind of like, because sometimes you just need to create a spectacle, and you need to be a little bit rebellious when you want to create change like this […] but it is totally legal. You know, a seven-year-old kid belongs on the road just as much as someone driving their truck to work in the morning, and that’s kind of the message we’re trying to send.

A city built for kids

Bike buses and bike trains are a growing international phenomenon, reflecting a desire among kids and adults to rekindle something that “nearly became extinct”: biking to school. As an activity organized for kids, they also reflect the work needed to let kids themselves make the city their own. Green had thoughts about how that could change.

Broadly speaking, kids could be stakeholders in city-building. We need to completely change our perspective on what we think our cities are for. Traditionally, they’ve been designed for things like people getting to and from work and kids really haven’t been a part of that equation at all. One step would be to have strategies in place that include children. For example, St. John’s has an Age-Friendly Cities plan, [but] I think it’s more geared towards seniors — which is great, but I think that should include kids as well. The existing hierarchy of transportation right now puts cars at the top; I think that needs to be inverted and focus on pedestrian and cyclist accessibility, which will benefit kids as well, and just making more space for kids to play and get around the city.

Given how entrenched driving has become in St. John’s, and how it has structured urban planning for decades, I asked Green if he thought it was too late for us.

I don’t think it’s too late. It’s going to take a lot of work, and it’s going to be a long-term project for sure. It’s going to require a major shift in thinking and some major systems change, but the city has changed before, and it can change again. The paradigm we’re in now is not that old really. It took a generation or two to create this current paradigm. I think in another generation or so we can completely change that, if there’s a will.

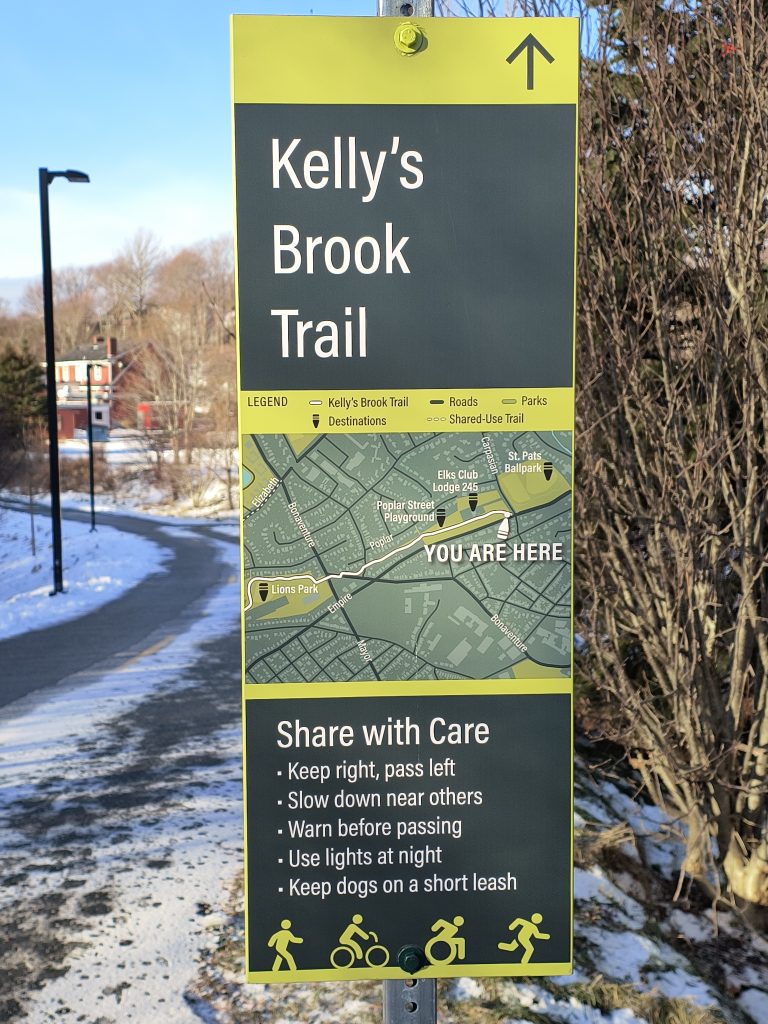

I am optimistic because I’ve seen this change in other places. […] Mindsets do shift and people become more accepting of it. I think you’re already starting to see that here in St. John’s. Before we started the shared-use projects [such as the Kelly’s Brook path], there was a lot of debate around our trails and bike-lanes and whatnot, and I think a lot of that is starting to dissipate somewhat as we’re starting to see these shared-use paths and people are starting to appreciate them more.

Things are finally coming together. The bike masterplan was approved in 2019, but I think this year is probably the first year we’re starting to see really tangible results. It’s fabulous to see all ages and abilities using those trails, and increased participation in cycling and other forms of active transportation.

The cost of doing nothing

In the time since our interview, at least two people—both senior citizens—have been killed while walking on streets or roads in Newfoundland and Labrador: one in Corner Brook, and the other in Ship Cove.

We started this interview talking about the tragedy on Montague Street. Kids, and adults too, are seriously injured or killed in St. John’s every year, and also in other places in the province. So that’s a pretty big cost, and you could argue that that is a result of designing the city for vehicles and […] getting vehicles around as quickly as possible. Many cities have Vision Zero strategies, which aim to reduce [traffic] fatalities to zero. I think that’s laudable, and I think it’s possible.

Originating in Sweden, but now gaining strength and success in cities from London to Montreal to Pittsburgh, Vision Zero takes a safe-systems approach to road safety, treating the lives and health of all road users paramount, not something to be traded off or balanced against speed and convenience for drivers. Because road users outside vehicles are most vulnerable, their safety is given priority. Importantly, Vision Zero assumes that humans will make mistakes. Instead of relying on personal responsibility to keep people safe, it preemptively addresses human fallibility in road design, so that an error does not become a tragedy. Of course, infrastructural changes that let walkers, cyclists, and other non-drivers get around safely have other transformative effects, not least as kids and their parents gain confidence in the safety of our shared spaces.

The other cost [of our current approach] is [to] kids’ independence, their freedom to be able to get around the city […] on their own with autonomy. I have an eight-year-old daughter, and she can’t really walk to a friend’s a block or two away because there’s an arterial road in the way and neither family really feels that it’s safe for her to get around some of these intersections. These are big costs that we don’t really talk about very much. I think we can do better and make it more equitable for everybody.

[It comes down to] a 180 [degree] mentality shift: inverting the hierarchy we have today, where we put motor vehicles at the top and pedestrians, cyclists, kids, at the bottom. We need to flip that and prioritize other modes of transportation. That also includes public transit.

Green counsels against succumbing to a “defeatist attitude” in the interim, noting recent positive changes have made a big difference and reflect the fact there are “people working quietly in the background [who] really care and are working hard.”

Those people, Green noted, include engineers and others at the City of St. John’s, who are working to expand active transportation infrastructure and introduce other measures to make streets safer for all users. They also include Green himself who, along with others in BNL, achieved an important change to the Highway Traffic Act: the one-metre rule, which requires drivers to leave at minimum a metre of space between their vehicle and any pedestrian or cyclist they are passing (1.5 metres where the speed limits is 60 km/h or above).

BNL continues to work for additional legislative reform designed to make our roads safer for all. For those who want to join the advocacy work, Green offered a range of options.

For people who just want to ride their bike, I would just say: “Just ride your bike. Just get a bike and ride it. The more you do it, the stronger you will be and the better it will get.” And for people who want to advocate for change, we have lots of fantastic groups here that are working on this stuff. So, certainly Bicycle Newfoundland and Labrador, Streets are for People, Happy City St. John’s, Ordinary Spokes, Vélo Canada Bikes: these are all volunteer-based organizations that could really use help in advocating.

For parents out there, or teachers who really care about kids’ transportation, mobility, and independence, I definitely encourage starting a bike bus at your school. It’s a really great way to get the ball rolling and get kids riding their bikes in the street, in a big group where it’s safe. You can certainly reach out to BNL and use Bishop Feild Elementary as a case study for that.

For everyone else:

Join something. Start meeting people. You can join the Critical Mass rides as well. That’s a good way to meet other cyclists. Just get involved, and start volunteering some time on these issues.