N.L. Election 2025

Let’s talk about the provincial election.

For many, elections are the linchpin of democracy, the moment when residents of a free and democratic society collectively choose the representatives and party they want to form government. True democracy comes from the ground up, but elections can be part of grassroots movements when voters organize, get change-makers elected, and hold them to account. It’s a monumental task and a great privilege to be elected. Politicians are not only decision-makers — they’re also law-makers who debate policies and pass legislation which directly impact our daily lives.

Fundamentally, democracy requires civic engagement by the people of a place: in knowledge and resource-sharing, advocacy, activism, public education around important issues, and participation in many other areas outside of electoral politics.

Between now and election day (Oct. 14) we will be unveiling more sections on this 2025 Provincial Election page, each focusing on a particular issue. (If there’s a topic you’d like to see addressed on this page, don’t hesitate to reach out and let us know.)

Before we get into some of the big issues facing Newfoundlanders and Labradorians, it’s worth brushing up on how democratic government in our province works. For that we turn to Political Scientist Alex Marland’s essay in the 2017 collection Marland co-edited with Lisa Moore, The Democracy Cookbook: Recipes to Renew Governance in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Beneath Marland’s essay, you will find a new piece written by former Indy Editor Drew Brown and a list of curated of articles from The Indy archives. Check back often because we’ll continue updating the list.

‘How Democratic Government Works in Newfoundland and Labrador’ (click to read)

By Alex Marland

Some people have a greater awareness of how government works, or of what democracy entails. The following primer about the nuts and bolts of politics and public administration is offered to assist readers with their comprehension of democratic government in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Context

In many ways, Newfoundland and Labrador’s democracy is outstanding, given the relative accessibility of the political elite and the government’s general responsiveness to public demands. It has come a long way from the political corruption and dire financial circumstances that led to protestors storming the Colonial Building in 1932 and ultimately the Commission of Government era, a period from 1934 to 1949 that entailed a ruling council comprised of a governor, three British commissioners, and three Newfoundland commissioners. Elections were put on hold throughout that period — an unusual case of the people’s elected representatives voluntarily relinquishing democratic government. It would be misguided to assume that the prospects of bankruptcy, or the reasons for it, were all that was wrong.

The Commission observed many embedded problems with governance such as the expectation of religious discrimination in the setting of electoral districts, in making appointments to cabinet, and during hiring in the public service. In the ensuing decades, power was concentrated in Premier Joey Smallwood and the provincial Liberal Party, and it is widely understood that he operated a “one-man government.”2 Other charismatic men — principally Brian Peckford, Clyde Wells, Brian Tobin, and Danny Williams — followed suit. The influence of religious institutions persisted well into the

1990s, with churches administering the denominational school system, a matter that was settled after two divisive referendums. Government is now a large, professional organization compared with its former self, and yet chronic challenges persist.

In other ways, Newfoundland and Labrador’s system of government is sorely in need of repair. In recent years considerable political and financial instability has constituted problems with the system itself, rather than with

any given individual(s). It is a vicious circle: electors reward leaders who respond to public demands, yet short-term thinking results in inefficiencies and inequity, leading to crisis and civil unrest. The upheaval undermines public confidence in government institutions and political leaders. And these are only the big-picture issues that the public knows about!

Warning: Democracy Is Messy

Reformers should bear in mind that everyone seems to love democracy and despise politics. A large gap exists between expectations for democracy and the realities of what it delivers. A sizable number of citizens are disengaged, with many Canadians seeing themselves as outsiders. As much as people might like the idealism of democracy, the struggle for power and influence inevitably results in a clash of opposing interests and frustration with systems and processes.

At the simplest level, a democratic system of government involves little more than the following: non-violent elections, a legitimate choice of options, citizens having the ability to determine who should be in power, and voters electing people to represent them in a legislature. Since Newfoundland and Labrador joined Canada in 1949, provincial elections have been held every four years or so as citizens elect people to represent them in the House of Assembly, from which an executive is formed. The province’s election campaigns may get heated, but they are bloodless affairs, and when a change of government occurs it is a peaceful transition. This does not necessarily mean that smooth governing will result, as captured by the brilliant title of Telegram reporter James McLeod’s book, Turmoil as Usual, within which he summarizes absurd situations that contributed to the latest bout of political instability.

Is democracy as we experience it really the best that Newfoundland and Labrador can do? Are our democratic expectations practical and grounded? The truth is that democracy is highly problematic wherever it is practised. While few citizens are familiar with the theories of democracy in the writings of Plato, Aristotle, and Hobbes, among others, much can be learned from them, as well as comparatively newer material and ways of thinking. Readers of classical and more recent theorists quickly learn democracy can be messy. The problems are nicely captured by Winston Churchill’s famous quip that democracy is the worst form of government — except for all the others. It is better than the alternative of authoritarianism or totalitarianism, but again, it is messy, as American political scientist John Mueller emphasizes:

. . . democracy has characteristically produced societies that have been humane, flexible, productive, and vigorous, and

under this system leaders have somehow emerged who — at least in comparison with your average string of kings or czars or dictators — have generally been responsive, responsible, able, and dedicated. On the other hand, democracy didn’t come out looking the way many theorists and idealists imagined it could or should. It has been characterized by

a great deal of unsightly and factionalized squabbling by self-interested, short-sighted people and groups, and its

policy outcomes have often been the result of a notably unequal contest over who could most adroitly pressure and

manipulate the system. Even more distressingly, the citizenry seems disinclined to display anything remotely resembling

the deliberative qualities many theorists have been inclined to see as a central requirement for the system to work properly.

Indeed, far from becoming the attentive, if unpolished, public policy wonks espoused in many of the theories and images,

real people in real democracies often display an almost monumental lack of political interest and knowledge. . . . But it must be acknowledged that democracy is, and always will be, distressingly messy, clumsy and disorderly, and that in it

people are permitted loudly and irritatingly to voice opinions that are clearly erroneous and even dangerous. Moreover,

decision making in democracies is often muddled, incoherent, and slow, and the results are sometimes exasperatingly foolish, short-sighted, irrational, and incoherent.

There is also widespread disagreement among scholars and citizens about the determinants and forms of democracy, as well as the many variables involved with good governance. For example, some of the contributors in this volume point to the importance of increased education and decolonization in providing the foundation for a better democracy. However, international research finds statistical evidence that a more vibrant democratic ethos is most strongly correlated with a higher standard of living, as measured through economic indicators such as per capita GDP. On this basis, the idealism of The Democracy Cookbook must be weighed against pragmatism and the need for strong leadership to achieve the art of the possible.

Who Are the Main Public Officials in Newfoundland and Labrador?

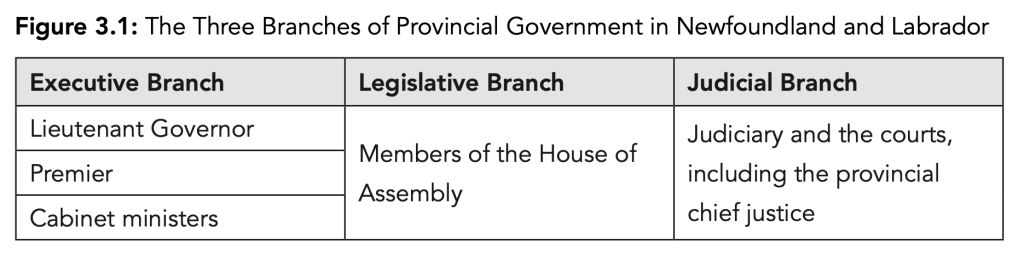

Descriptions of a democratic system typically emphasize institutions, namely the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. Instead, let us begin by identifying who the key political actors are, and situate where

they fit within the government system.9 The provincial system’s key actors are identified in Figure 3.1 and are described below.

Newfoundland and Labrador’s system of parliamentary government revolves around the ability of citizens to elect representatives. A Member of the House of Assembly (MHA) is one of 40 people elected to the provincial legislature, which is located in the Confederation Building in St. John’s. Each MHA represents the residents who live in one of the 40 constituencies drawn on an electoral map of the province. There are 36 ridings on the Island of Newfoundland and four in Labrador.

All systems for electing representatives are problematic. The single-member plurality method of electing MHAs is routinely criticized. The candidate with the highest number of votes wins the seat, in a method commonly known as first-past-the-post — similar to how a racehorse who crosses the finish line first is the winner, except that in this electoral system there is no reward for placing second. To some, this creates a problem when a number of close races are won by the same party and weaker parties are shut out. As a result, the governing party tends to be over-represented in the House of Assembly and opposition parties are under-represented, particularly small parties whose support is spread across many electoral districts. Supporters count stability and simplicity among the strengths of the first-past-

the-post system. A further issue is that the composition of the legislature, as elsewhere in Canada, is not sufficiently representative of the socio-demographic characteristics of those being governed. Though things have been improving, most obviously women have been under-represented in the House of Assembly, as well as in the executive branch and the judiciary.

Another important aspect of elections is party finance. The rules for donating monies to political parties or candidates, and how money is spent by them and by others (e.g., interest groups, businesses, labour unions, private individuals), have been changing in other provinces. In Newfoundland and Labrador the political parties have displayed little interest in discussing reform, which is exactly why it must be discussed.

Most candidates and MHAs are affiliated with one of three provincial political parties: the Liberal Party, the New Democratic Party (NDP), or the Progressive Conservative (PC) Party. Since 1949, provincial governance has alternated between the Liberals and PCs, with the NDP perpetually the third party. An outsider might think that the PCs are right-wing (i.e., supporters of small government and traditional values), the NDP left-wing (i.e., advocates of big government and progressive values), with the Liberals straddling the political centre. In fact, by national standards, all three parties are more likely to huddle to the centre/centre-left on the ideological spectrum. The politics of Newfoundland and Labrador is a mix of traditional and socially progressive values, and above all resistance to free market forces in favour of big government, particularly if that involves securing funding from Ottawa. In many ways, the province’s politics are a homogeneous monolith, such that “it is often difficult to distinguish Newfoundland parties in policy space.” Where the parties differ is their relationship with their federal cousins. The Liberals and NDP are deeply connected to the national parties that bear the same name, which means they share resources and often copy federal party policies, to the point that the provincial party is almost an arm of the national counterpart. Conversely, the Conservative Party of Canada, as constituted in 2004, has no formalized link with any provincial political party and some of its libertarian policies are shunned in Canada’s easternmost province. Certainly there are connections between it and the provincial PC Party, but these are not as strong as federal–provincial connections among the other parties.

Whatever their party, members who are elected to represent an urbanized area such as St. John’s are likely to represent the highest number of constituents. MHAs in rural areas, particularly Labrador, have fewer constituents spread across a large land mass. On the floor of the House of Assembly, members are seated together by political party. Those with additional responsibilities, such as party leaders and ministers, are seated at the front of their respective groupings. Those with the least responsibility are seated behind them and are thus known as backbenchers. The role of an MHA is varied but typically involves helping constituents get access to government services, attending local events, listening to

concerns, delivering statements in the House of Assembly, voting on bills, and communicating through the media. A constituency assistant helps each MHA with electoral district issues and sometimes works out of a constituency office in the riding.

Electing people to the House of Assembly is designed to ensure that the delegates of the King or Queen of Canada do not make government decisions without considering the views of the people. The Lieutenant Governor of Newfoundland and Labrador is the person appointed at the recommendation of the Prime Minister of Canada to represent the Crown’s interests in the province. At a glance, the position hearkens to the British governor who oversaw the earlier Commission of Government. A lieutenant governor holds formal powers of appointing a premier to recommend a cabinet, granting royal assent so that a bill may become law, assenting to the decisions of the cabinet to create Orders of the Lieutenant Governor in Council, proroguing a session of the legislature, and signing a writ of election. The Canadian custom is that lieutenant governors rubber-stamp what is asked, and rise above political debate by concentrating on ceremonial duties. This includes reading the Speech from the Throne, handing out awards and medals, and hosting an annual tea party that is

open to the public at Government House in St. John’s.

The Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador is appointed by the lieutenant governor to head up the government, based on which party controls the most seats in the legislature. This occurs after a general election, unless a premier leaves the office before then, prompting the appointment of a successor. The premier is also the leader of the political party that controls the House of Assembly, and he or she, therefore, is expected to be an MHA. This individual alone recommends who to appoint to cabinet, who to demote, and who to shuffle out. Thus, it is foremost the premier who steers the shape and direction of government, with the support of political staff in the Premier’s Office, who are partisan appointments. Political power is primarily concentrated in this single individual, both a strength and weakness of parliamentary models of democracy.

The Premier’s Office also has access to astute non-partisans in the Cabinet Secretariat and Communications Branch, among others. The most senior public servant is the Clerk of the Executive Council, who serves at the pleasure of the premier and is in constant contact with senior officials throughout government. The clerk navigates implementation of the premier’s political agenda as well as requests emanating from departments.

A cabinet minister is a person appointed to be a member of the Executive Council of government. All ministers are members of the party that controls the legislature and almost always are MHAs. Ministers are assigned responsibility for portfolios, including a government department and/or government agencies. This means that they spend time overseeing

their department while also having a presence in the legislature and dealing with constituent concerns. Their oversight of a department is much more hands-on than is the case with an arm’s-length agency such as a Crown corporation, which faces competitive pressures in a private-sector marketplace.

Collectively, as a cabinet, ministers make broad decisions, whether in cabinet committees or in full cabinet meetings. Individually, as ministers, they are responsible for their own portfolios. As a group they are faced with balancing the needs of the province as a whole with the needs of their political party. By convention ministers must publicly support each other and vote with the government or else they must resign from cabinet. An outcome of the cabinet being embedded in the legislature is that this instills strict party discipline on backbenchers in the governing party, who

are expected to vote with the government. Each minister is supported by political staff and by non-partisan public servants in the department. Just as the premier works with the clerk of the Executive Council, a minister works with a deputy minister, who is the deputy head of the respective department. The clerk and deputy ministers (DMs) carry out their duties in a non-partisan manner, though to what extent they are apolitical depends on the individual. Both the clerk and DMs are accountable ultimately to the premier rather than to a minister.

A parliamentary secretary is an MHA with the governing party who is appointed to assist a cabinet minister with select duties. Serving in this role is often perceived as training ground for a future cabinet appointment. On the opposite side of the House is the Leader of the Official Opposition. This is the leader of the political party that has the second-most seats in the House of Assembly. The position, while significant, does not hold much legislative power because the party is not in charge of the government. However, as the premier’s main critic including during Question Period, the opposition leader and the official opposition as a whole can complicate the ability of the governing party to advance an agenda.

Business in the House is moderated by the Speaker, an MHA who is usually a member of the governing party. The speaker does not vote except in the event of a tie. To manage daily activities, each party designates an MHA as their House Leader to negotiate proceedings, which tend to be directed by the government House Leader. Opposition MHAs assume critic

portfolios to counter or shadow government ministers. Members on both sides of the House participate in various legislative committees to closely examine government business. Far too often the Committee of the Whole is used, a form of committee that includes all MHAs except the speaker, who simply exits the chamber so that it may be chaired by the deputy speaker.

An important principle of democratic governance is the rule of law. This means that power cannot be used in an arbitrary fashion. The highest law of the land in Newfoundland and Labrador is the Constitution of Canada, which outlines the division of powers between the federal and provincial governments, and which includes the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Supreme Court of Canada, which is located in Ottawa, is the top court in the country and is entrusted to be the final judge or arbiter on legal disputes and interpretations of national significance. In St. John’s, the Supreme Court

of Newfoundland and Labrador considers civil cases and criminal matters, and listens to appeals. Judges have considerable power, yet the province’s process for appointing lawyers to the bench is somewhat opaque. As well,

the mechanisms to hold them to account do not involve public input even when there is public outcry over decisions.

The power of politicians and the public service in Newfoundland and Labrador is structured and constrained by the federal Constitution. For instance, if a bill is passed by a majority in the House of Assembly, and then signed into law by the lieutenant governor, the courts may nevertheless strike down the legislation if it is deemed to be unconstitutional. Reforming the Constitution is a topic that prime ministers have been unwilling to tackle since the failure of two divisive constitutional accords and two Quebec separation referendums in the late twentieth century.

How the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador Is Organized

The main actors in each of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government contribute to making and interpreting decisions about public policies. In various ways this includes laws, practices, regulations, standards, and other legal instruments. A key difference between the federal and provincial levels of government is that there is only one legislative chamber in Newfoundland and Labrador, whereas the Parliament of Canada in Ottawa is comprised of the House of Commons and the Senate. Legislation moves comparatively swiftly through the House of Assembly due to the

underutilized nature of review committees, under-resourced opposition parties, limited journalistic scrutiny, and a slew of other factors. Legislative business can nevertheless take quite some time to move through cabinet, then through the House, and then potentially on to the lieutenant governor for signature.

When trying to determine how much power a governing party has, the first thing to identify is not the party’s standing in public opinion polls, but rather whether the party has a majority of seats in the House of Assembly. If so, the premier and cabinet can advance an agenda with confidence that it will be supported by enough MHAs to win a vote. Majority governments are prevalent in Newfoundland and Labrador, adding to the power that is concentrated in the Premier’s Office. The main alternatives are a coalition government (the formal working union of two or more political parties that

control the legislature, which then have a role within cabinet) or a minority government (whereby the premier’s party does not control the legislature and has to negotiate with other parties in order to remain in office). Coalition governments are rare in Canada, in part a function of the electoral system and political culture. Minority governments are reasonably common across the country. They are unusual in Newfoundland and Labrador, which had a single brief experience with minority government in the early 1970s as the era of Joey Smallwood government came to an end.

The House of Assembly precinct is also a bit odd in that it is nestled within a government building that employs public servants. More significantly, the Premier’s Office and a number of ministers’ offices are in that same edifice. Thus, while the legislative branch is meant to hold the executive branch to account, there is symbolism in the fusion of these organs of government into the same space. The precinct includes the press gallery, an area reserved for accredited journalists. Conversely, Crown corporations are situated in independent buildings.

Democracy is embodied in the premier and ministers overseeing the bureaucracy. They seek to implement their election agenda and generally act as the people’s representatives among the permanent public service. These politicians take credit for good news announcements and they bear the brunt of criticism when controversy arises. Unlike them, a public servant is not elected, typically has job security, and is not the public “face” of the department. Many if not most are hired through the merit principle, which is to say that individuals deemed the best candidates in publicly advertised job competitions are generally the ones hired. Public servants are non-partisan and follow a working premise that they should provide frank advice to ministers and loyally implement whatever a minister decides, within the boundaries of the law. They tend to have specialized training, finely honed skill sets, institutional memory, and, above all, a respect for following a chain of command and formalized process mechanisms. By comparison, their political masters may have no training in the departmental area whatsoever and an impatient desire to implement decisions quickly. But what a minister

does have is the legitimate authority to make decisions. Moreover, a minister and political staff are highly in tune with political realities. It is common for public servants to become frustrated by the political agenda being pursued by cabinet or the lack of resources allocated to a file. Other times a department may find itself the centre of public attention and

pressured to take action. No matter what the circumstance, a public servant is expected to separate personal political opinion from a duty to carry out directives. This long-standing principle is itself subject to question, given the

importance of protecting whistleblowers, another area of reform that has been slow to emerge in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Across Canada, the size of provincial governments has been growing, which in large part is a reflection of the expanding importance of health care and education in particular — both of which are assigned as a provincial responsibility by the Constitution. Another major area of provincial jurisdiction is non-renewable natural resources. Other responsibilities

include lands, licensing, some forms of taxation, and overseeing municipalities. At any given time the number and names of departments and agencies vary. Among the most prominent are health, finance, education, natural resources, justice, and public works. Others ebb and flow, such as environment or tourism, and the federal government plays varying

roles in some areas, such as the fishery. A reader interested in the latest configuration of government departments need only visit the relevant area of the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador website.

Space prevents a deeper discussion about public administration and politics in the province; for a good overview, see work by Christopher Dunn and the publications of the 2003 Royal Commission on Renewing an Strengthening Our Place in Canada (2003). Historical perspective is also instructive, such as publications authored by Sean Cadigan, Henry Bertram Mayo, Susan McCorquodale, and S.J.R. Noel. Equally, to get a sense of the problems that result when transparency is lacking in political decision-making, a reader might consult the 2007 report of the Review Commission

on Constituency Allowances and Related Matters. While there is little point in fixating on singular events, it is worth pointing out that even though institutional reforms contribute to better governance, bad habits are prone to creep back.

How the Government Decides

So how is government policy formulated? Primarily through the implementation of the governing party’s election platform. Those promises are formalized in the Speech from the Throne, which is prepared by the governing party and read by the lieutenant governor on the floor of the House of Assembly. The speech is peppered with “My government will

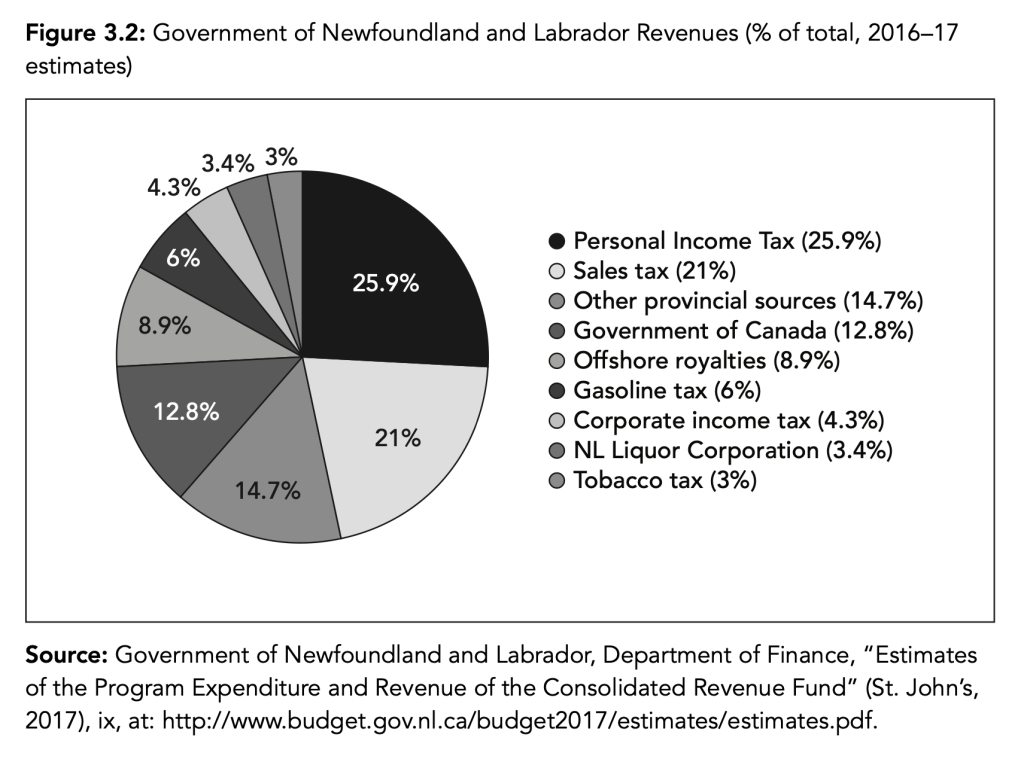

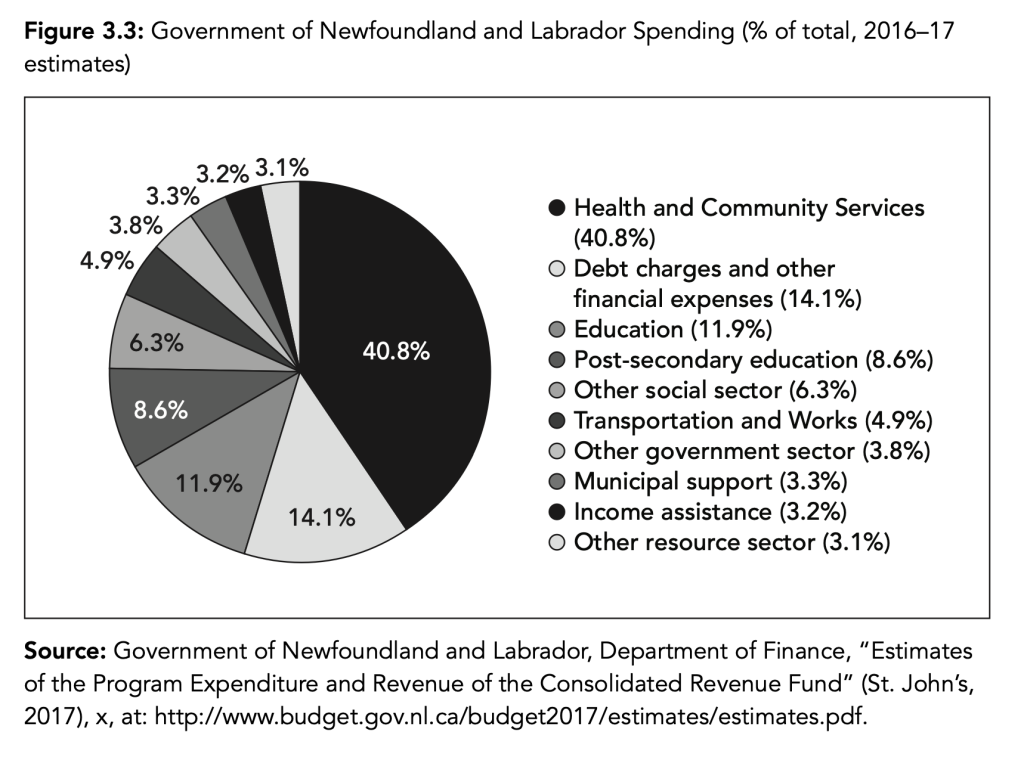

. . .” statements that provide direction to the public service about the government’s immediate agenda. At the start of every fiscal year, roughly in March or April, the finance minister delivers a budget that identifies how the government proposes to raise and spend money. Figures 3.2 and 3.3 provide a snapshot of where the government obtains its revenues

and where the money goes. The budget tends to be the centrepiece of implementing aspects of the election platform and Throne Speech, though it may equally adapt to emerging political circumstances. The budget must be supported by a majority of MHAs; otherwise, the government falls and there must be a general election. Time is devoted to MHAs debating the budget and reviewing financial estimates. Other routine activities in the legislature include debates over issues of the day during Question Period and the introduction of new bills. The cycle repeats itself each year, with the

House meeting roughly in March, April, May, November, and December — a bit more in years when there is urgent business and quite a bit less in election years.

Issues in the news are more likely to command political attention, to enter what is known as the public policy cycle, and to get on the public agenda. Within the government there are many instruments used to manage information flow. Chief among them is a memorandum to cabinet, which is advanced by a minister to request that cabinet authorize a course

of action. A cabinet memo applies all sorts of policy lenses on proposed actions to help ministers consider a plethora of perspectives. When submitted to cabinet it is normally referred to a committee of ministers, which invokes review by staff in the Cabinet Secretariat. This process brings a government-wide perspective to departmental initiatives. Government announcements are formally communicated through news releases and speeches. Increasingly, the government is availing of communications technology, such as social media and so-called “open government” to

make information publicly available online. Other matters occur behind closed doors and go undocumented, such as meetings between ministers and interest group leaders.

Communications technology is at the heart of reasons why traditional ways of governing suddenly seem outdated. It is one thing to be able to get a minister to respond to public concerns on local call-in radio programming, a phenomenon more prevalent in Newfoundland and Labrador than in other provinces. It is quite another to exchange information around the world in real time via Internet-enabled portable devices. Media elites no longer act as gatekeepers who control what information can be circulated, though government elites continue to spin messages and obscure information. The tiniest of details are now pounced upon in the online public square. Events in remote areas of the province can be documented by citizens who have the technological means to share their stories. Interest group leaders can quickly co-ordinate a public protest. Journalists tweeting news and public opinion polls act as barometers of the public mood. Even so, traditional television news still dominates, though the intersection with Internet video means that exposure to local media and engagement in local public affairs are changing.

A strong, vibrant democratic society is characterized by pluralism — the “marketplace of ideas,” to use a long-standing expression featured in VOCM radio’s promotion of its call-in shows. Information about government should be publicly available and the public should welcome spirited conversations about a full range of policy options. An ideal democracy

would treat its citizens reasonably equally and welcome competing points of view. In such a society, coffee houses and talk radio shows, as well as public consultation forums and the Twitterverse, should engage the public towards coming up with thoughtful solutions to public problems. Citizens and their leaders should be sufficiently open-minded to consider new ways of doing things and to balance compromise with bold decision-making.

Reforming Democratic Governance in Newfoundland and Labrador

Is democratic governance working for Newfoundland and Labrador? Is it the best it could be? What is the ideal process for premiers, ministers, and MHAs to make decisions on behalf of the public, particularly when those decisions are difficult and potentially unpopular? These are questions without definitive answers.

Echoing themes of their federal counterparts’ interest in promoting democratic reform, a core plank of the provincial Liberals’ election platform in 2015 was better government through “openness, transparency and accountability.” On the surface, some themes were alternately well intentioned or mostly campaign rhetoric, such as a pledge to “respect” the House of Assembly, to “encourage co-operation,” and to “respect diversity.” Specific promises included creating a non-partisan Independent Appointments Commission; amending the House of Assembly Act to set a schedule for House sittings; reforming the standing orders of the House; implementing “family-friendly policies” to support gender diversity in the workforce; discontinuing the salary top-up for parliamentary secretaries; and regularly holding town halls across the province. Others were less concrete, such as a pledge to “make better use of existing committees” and a commitment “to open communication, consultation, and collaboration with Aboriginal communities.” Moreover, the platform was silent on many aspects of democratic reform. By comparison, the federal Liberals proposed action on electoral reform, free votes by parliamentarians, leaders’ debates, government advertising, judicial appointments, officers of the legislature, omnibus bills, parliamentary committees, political financing, Question Period, greater diversity and engagement in government, and more.

The Liberal Party of Newfoundland and Labrador left open these possibilities by promising to create a committee on democratic reform that would be comprised of MHAs from all three political parties in the legislature. A Stronger Tomorrow: Our Five Point Plan states:

A New Liberal Government will form an all-party committee on democratic reform. This committee will consult extensively with the public to gather perspectives on democracy in Newfoundland and Labrador, and make recommendations for ways to improve. The committee will consider a number of options to improve democracy, such as changing or broadening methods of voting to increase participation in elections, reforming campaign finance laws to cover leadership contests, and requiring provincial parties to report their finances on a bi-annual basis.

Aspects of the election platform were formalized in mandate letters from the premier to ministers. The minister responsible for the Office of Public Engagement was directed to “host regular engagement activities including town hall meetings in communities throughout the province and use technology to expand the options to participate.” The government House Leader was instructed to “modernize the province’s legislative process and engage elected representatives from all political parties” and to “make better use of existing committees and seek opportunities for

further nonpartisan cooperation, including establishing legislative review committees to review proposed legislation.”

Most significantly, the House Leader was expected to “Bring a resolution to the House of Assembly to establish an All Party Committee on Democratic Reform” (emphasis added). While the March 2016 Speech from the Throne further formalized some commitments, such as creating the Independent Appointments Commission, it did not mention the all-party committee on democratic reform. Nor did the 2017 Throne Speech.

In the current context a barrier to change is limited resources. Deep research is required on the scale of the aforementioned Review Commission on Constituency Allowances and Related Matters, commonly known as the Green Report after its namesake, Judge Derek Green. The constituency allowance scandal involved a systemic misappropriation of funds allocated to MHAs for work-related expenses. Thanks to the Green Report, considerable reforms to the internal financial management of the House of Assembly were implemented, through the creation of the House of Assembly Accountability, Integrity and Administration Act (2007). After the reforms, Newfoundland and Labrador became a model for legislatures in Nova Scotia, the United Kingdom, and the Parliament of Canada when those institutions were embroiled in similar scandal. “For true transparency and openness, the House of Commons should follow Newfoundland’s

example,” concluded parliamentary scholar C.E.S. Franks. More recently, Rob Antle, a seasoned journalist who followed the constituency scandal, observed that “the current system is working” in the province because the Act required transparency of otherwise hidden political decisions. Those reforms are evidence that high standards of professionalism and open government are possible.

Meaningful democratic reform is possible no matter what the financial circumstances of the province. We must not be satisfied with Churchill’s notion that democracy is automatically better than the alternatives. Improvements must constantly be made for that to ring true.

The Independent is proud to present a two-part analysis of Newfoundland and Labrador politics written by Drew Brown, whom we asked to help us better understand our province’s political system. “We’re stripping it down to the fundamentals here. The simplest way to orient politicians and parties in this province is along three spectrums,” Brown writes. “The first is the classic ‘left-right’ spectrum, which is all about how people distribute social power and economic resources. The second is the federalist-nationalist spectrum, which relates to the place of our province in Canada. The third is the technocratic-populist spectrum, which is about who has the authority to make government decisions.”

PART 1: Defining Newfoundland and Labrador’s political system in 2025 (click to read)

Can standard dichotomies like ‘left and right’, ‘nationalist and federalist’, or ‘populist and technocratic’ help us understand politics in the province?

By Drew Brown | Analysis | Sept. 25, 2025

Have you ever gazed out over the roiling political landscape of Newfoundland and Labrador and thought to yourself: what fresh hell is this? Who are all these people and what are they talking about? How am I supposed to know who to vote for when all the parties seem the same? And why can’t the NDP ever seem to get it together and win a provincial election?

You are in luck! The Independent is proud to present this general guide to understanding politics in Newfoundland and Labrador. We’re hopeful it will serve as a road map through as many provincial elections as it takes for the federal government to repossess the House of Assembly as part of the inevitable bankruptcy proceedings.

In Part 2, Brown will delve into the unique aspects of political life in Newfoundland and Labrador, “for better and for worse,” he says. Sign up for our free newsletter and we’ll let you know as soon as it’s out.

PART 2: How N.L. became the life (and death) of the party (click to read)

We’re cutting through the undergrowth to find out why our political parties feel dead — and what might liven them up

By Drew Brown | Analysis | Oct. 6, 2025

Hello dear voter!

In Part 1 of this field guide to Newfoundland and Labrador’s distinct political system, we focused on how easily our three major political parties — Liberal, Progressive Conservative (a.k.a. Tory), and New Democrat — could be mapped along the coordinates we use for talking about politics in general: left or right, federalist or nationalist, technocratic or populist. As we discovered, while there are clear distinctions between each party, the Liberals and Tories are pretty flexible as far as their principles go depending on their proximity to state power. (We have yet to see how the NDP would hold up in that crucible.)

Whether you view this flexibility as a feature or a bug depends on where you stand. On the one hand, to quote Rowdy Roddy Piper in They Live, “the middle of the road is the worst place to drive.” On the other hand, to paraphrase a tweet from former Telegram reporter Peter Jackson in response to me quoting that line at him, “the ruts are deepest in the left and right lanes.”

We can put this vehicular metaphor into overdrive and spin out a few useful questions. What are the official (and unofficial) rules of the road? What kind of driver is behind the wheel? What is the make and model of each car? What are we going to find if we check under the hood? In other words, how exactly do political parties in this province work?

Buckle up — the next part of this crash course will take us over a few potholes.

The Independent takes the state of our province and democracy seriously — not only at election time, but year-round as we publish stories that not only critique government and corporate interests but also focus on solutions to the injustices so many in Newfoundland and Labrador experience on a daily basis.

Bookmark this page and keep checking back because we’ll be updating it with information, stories and election promises from parties on key issues facing Newfoundlanders and Labradorians. You can also sign up for our free newsletter and we’ll let you know when we have more to share.

Party Platforms

For your convenience here are links to the NDP, Progressive Conservative and Liberal Party platforms, in the order the parties released them.

New Democratic Party: “A better deal for people in Newfoundland and Labrador“

(Released Sept. 26, 2025)

Progressive Conservative Party: “For all of us“

(Released Oct. 8, 2025)

Liberal Party: “Our plan for Newfoundland and Labrador“

(Released Oct. 8, 2025)

Government Transparency & Accountability

Transparency and accountability are inherent to a healthy, functioning democracy. The public needs information about our elected officials, how they represent us, and how they arrive at the decisions they. Accountability is also vital to democratic governance because politicians will, and do, often act in their own self-interest (or in a conflict of interest) when there are insufficient rules or consequences to prevent them from doing so.

Here is a curated list of Indy stories and analysis pieces related to transparency and accountability in the context of our provincial government…

- Revolving Door: The problematic relationship between politics and business in N.L.

- Only Province in the Dark: Inside N.L.’s broken ethics system

- Liberal cabinet ministers, PC MHA have not filed public disclosures: Commissioner

- Seismic shift needed to address N.L. housing crisis, experts say

- We’re heading toward another Churchill Falls disaster, and we’ve been warned

- Housing minister refuses to say housing is a human right

- About that Apology

- Where’d the politicians go?!

- Liberals Quietly Pitch Province as “World’s First Net-Zero Potential Energy Super Basin”

- Andrew Furey’s Liberals Have a Legitimacy Problem

- Andrew Furey Reneges on Transparency Commitment

- The Fight for Any Future Jane Doe

- Why Play a Political Game That’s Rigged Against You?

- I’m a Newfoundlander Born and Bred and I’ll Owe Debt Til I Die

Housing and Homelessness

Housing was recognized as a human right in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. As part of its international obligations, Canada also recognized housing as a human right in its National Housing Strategy Ac in 2019.

Yet when asked by The Independent if he agreed housing is a human right, former NL Housing Minister Fred Hutton would not say. This illustrated the gap between Canada’s commitments under national and international law and the reality in our province.

Since the pandemic, the province has experienced a worsening housing crisis, with rising home prices and shrinking affordable housing. According to the Consumer Price Index, Newfoundland and Labrador experienced the highest rent increase in the country over the past year, at 7.8 per cent, surpassing Canada’s overall average of 5 per cent.

A report by the Community Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador and Annex Consulting found that the province has less public housing than the rest of Canada, making up just 0.3 per cent of all housing in NL compared to 4 per cent across the country.

End Homelessness St. John’s has reported an estimated 1,400 people experienced homelessness in St. John’s in 2024 (400 on any given night), a more than 50 per cent increase from 2022. Given the lack of available public housing or shelters, the provincial government has turned to private operators. The NL Housing Corporation spent $8.1 million on for-profit housing in the 2024-2025 fiscal year, data shows. Advocates have also criticized policies that remove unhoused residents from rural communities into shelters in larger centres, sometimes hours away from their home communities.

Here are some stories and analysis The Independent has published on the housing and homelessness crisis in NL:

- Seismic shift needed to address N.L. housing crisis, experts say

- Housing minister refuses to say housing is a human right

- Why it matters that Fred Hutton won’t say housing is a human right

- No more encampment evictions, says federal housing advocate

- The case for affordable housing

- Let’s make housing and mental health an election issue

- Transitional housing facility in Happy Valley-Goose Bay will be built next year: MHA

Climate Crisis

Newfoundlanders and Labradorians are facing a worsening climate crisis marked by intensifying heat and droughts, coastal erosion, flooding, and more intense wildfire seasons which have led to community evacuations. In Labrador, sea ice is forming later and is less predictable, disrupting Inuit ways life including travel and hunting practices and contributing to food insecurity.

Despite this, and commitments to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2025, the province continues to invest in oil and gas production — the largest driver of climate change — including investments in delayed projects like Bay du Nord. In the 2025 budget, the provincial government promised to invest another $111 million in the oil industry between 2026 and 2029.

Many are also concerned about Newfoundland and Labrador’s continued reliance on an industry that is both volatile while the world is expected to reach peak oil by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency.

The incoming provincial government will need to take urgent and decisive action to address the growing impact of climate change. This includes adapting to climate change and investing significantly in mitigation efforts. Newfoundland and Labrador is also not yet meeting its climate goals of reducing emissions by 30 per cent by 2030, 60 per cent by 2040, and achieving net zero by 2050.

If elected, the Liberal Party says it will continue to work towards its 2025-2030 adaptation and mitigation strategy, which includes investing in renewable energy projects and creating more eclectic vehicle charging stations

The NDP is promising a Future Industries Secretariat that will create climate-focused jobs while identifying and preparing new renewable energy projects.

The PCs say they will create new sector-specific emission-reduction targets, encourage green innovation by funding local research, improve the oil-to-electricity incentive program, and engage with Indigenous communities to discuss the effects of climate change.

All three parties will continue to invest in the oil industry but the NDP has not committed to expanding it as the other parties have.

Here are some curated stories and analysis to get you started on learning about the climate crisis in Newfoundland and Labrador:

- Ignoring climate change in the provincial election will have ‘devastating consequences’, say youth and labour leaders

- ‘Close to panic level’: Survey respondents chime in on climate crisis

- Liberals’ climate action plan ‘misses the mark’

- Liberals’ gamble on oil and gas in Budget 2025 ‘worrisome’, says MUNL researcher

- Bearing the brunt of climate change in Nunatsiavut

- Decolonizing climate action

- Can the cap address the gap? The growing chasm between climate rhetoric and reality

- N.L. parties agree we need more say on fisheries — but what about climate change?

Fisheries & Oceans

The ocean and fisheries remain fundamental to Newfoundland and Labrador’s identity and economy. Seasplainer co-authors Jenn Thornhill Verma and Leila Beaudoin asked party leaders how they would navigate federal jurisdiction to advocate for the province’s fishing and coastal communities, and what provincial tools they would deploy to support sustainable fisheries and coastal livelihoods.

They asked each party leader:

- While fisheries and oceans fall under federal jurisdiction, what role should the province play in shaping ocean and fisheries policy, and what specific priorities would your government advocate for with Ottawa?

- What provincial tools—such as coastal zone management, aquaculture regulation, or support programs—would your government use to support sustainable fisheries, healthy oceans, and coastal communities?

All three major parties responded, each emphasizing the need for a stronger provincial voice in fisheries management, though their approaches differ in tone and specificity.

All three parties agree the province needs a stronger voice with Ottawa and that sustainability must balance environmental protection with fisheries livelihoods. But they diverge sharply on approach: the NDP prioritizes research and data, the PCs name specific policy battles like increasing fisheries markets, including for seal, and opposition to the proposed marine protected area on the south coast, while the Liberals emphasize pressing ahead on their current advocacy with the federal government.

Meanwhile, no leader spoke to climate change and Canada’s role in international ocean governance—despite mounting global urgency.

Read more of our fisheries and oceans coverage…

- Politicizing science: how quota quarrels lose sight of sustainable fishing

- The fatal truth about commercial fishing

- DFO ‘rolling the dice’ with cod fishery announcement, says scientist

- Is Northern cod on its way back from the brink?

- How Climate Change is Threatening Our Fisheries

- Why are NL fishers going out of province to land their catch?

- Who Decides the Price of Fish at the Wharf?

Post-Secondary Education

Our province’s public post-secondary system dates back to the founding of Memorial College in 1925, a foundation on which a public university and college system was built.

In 1999 the province bucked national trends by freezing tuition fees, then rolling back fees by 25 per cent over the next three years, creating one of the most financially accessible post-secondary systems in the country. Over the next decade, the province progressively poured funding into the system, converting much of the provincial student loan system into non-repayable grants and eliminating interest on existing provincial student loans, among other measures.

The payback was significant: post-secondary students from across the country and world flocked to the province, many of them staying after graduation to build lives here and helping to counter Newfoundland and Labrador’s ongoing outmigration and population crisis.

In 2018 the system began to crumble as the provincial government allowed Memorial University to increase fees, first for international students and Canadian students from outside NL, and then for NL students as well. This has occurred amid a backdrop of broader funding cuts to the post-secondary system which have led to faculty and staff layoffs and increased reliance on precariously employed contract instructors. Over the past decade, the universitlost 50 per cent of its provincial funding.

The question of who is responsible for the province’s post-secondary system is a matter of intense debate. Student activists and advocates for accessible post-secondary education say funding the public post-secondary system is the provincial government’s responsibility, pointing to the long legacy of government involvement in public post-secondary education here. Opponents of this perspective argue the university ought to be self-reliant and fund itself through tuition fees and other measures similar to universities in other provinces.

Memorial has been the subject of scrutiny in recent years on a number of rights-based issues. The university’s implementation of a code of conduct and its repercussions against a student protestor sparked a notable legal challenge in 2021 which the university lost, and a Charter challenge is presently underway over Memorial’s involvement in a police raid to clear a Palestine solidarity occupation in 2024, which led to three students’ arrests (charges were later dropped). Former Memorial president Vianne Timmons was terminated by the university in 2023 following national controversy over her claim to Indigenous heritage, and Memorial Board of Regents Chair Glenn Barner also resigned in 2024 following complaints of inappropriate behaviour and violations of university privacy policy in regards to Palestine solidarity protests on campus.

Here are some stories and analysis The Independent has published on post-secondary education in NL:

- What are universities for?

- Why is Tuition Thawing Now? Following the Money at MUNL

- It’s time for a reckoning on public university education in our province

- Memorial president treading in murky waters of university’s conflict of interest policy

- Banned Student Threatens Legal Action Against MUNL

- Student Taking MUNL to Court Over Punishment for Protest

- MUNL to Retract Ban on Student Protester, says Lawyer

- From Black Excellence to Black Flourishing at Memorial University

- Memorial University students can’t afford silence

Gender

Women make up a small majority of Newfoundland and Labrador’s population, according to Statistics Canada data, which has also found the province to have a statistically large and growing non-binary, trans and gender-diverse population. Yet gender-based equity struggles continue to dominate the social and political landscape here.

Pay equity has been a longstanding issue. In 1988, NAPE negotiated a pay equity agreement with the province that would see women healthcare workers paid equally to men. But in 1991 the Clyde Wells government passed legislation cancelling equity payments, citing the province’s poor economic situation. It wasn’t until 2022 that the province finally passed the Pay Equity and Pay Transparency Act. But labour advocates have widely criticized it as inadequate.

The province has had a mixed history when it comes to other gender-based initiatives. In 2015 a transgender activist took the government to court and won a legal victory requiring the province to make it possible for people to change their sex designation on provincial government documents. A 2017 court case in the province brought forward by another trans activist paved the way for the non-binary ‘X’ marker to be adopted on Canadian birth certificates and other legal documents, and the province has ranked highly in new Statcan surveys of the 2SLGBTQ population.

The province ranks poorly, however, when it comes to accessing gender-affirming healthcare. Existing barriers to accessing healthcare in the province—particularly the lack of physicians and medical professionals—are exacerbated for those seeking gender-affirming healthcare. Relatively few gender-affirming care surgeries are accessible through the public healthcare system in NL. The dearth of surgeons, coupled with travel costs and an inadequate Medical Transportation Assistance Program, creates barriers for gender-diverse people in the province.

The province has thus far remained relatively free of the types of anti-trans rhetoric and bigotry adopted by Conservative politicians in some other provinces.

Here are some stories and analysis The Independent has published on gender in Newfoundland & Labrador.

- Where is gender on the agenda in the N.L. provincial election?

- Will gender parity and a comparatively diverse slate of candidates pay off for the provincial NDP?

- Marking Pride month amid ‘emboldened’ rise in prejudice, bigotry

- “Pride is political”

- Fighting for Choice and Bodily Autonomy

- Only Community Care Can End Gender Based Violence

- Hundreds Turn Out to Support 2SLGBTQIA+ Rights and Inclusive Education

- Trans March 2024: ‘The struggle is more important than my fear’

- Women and the 2021 NL General Election

- Budget backlash continues with anti-violence protest

- Trans Day of Remembrance 2024: Reflecting on more than a century of trans culture and activism

- Status of Women debate a historic first for N.L.

Share your thoughts on the election issues on this page. We’d love to hear from you!

Page last updated: Friday, Oct. 13, 2025 (11:07 a.m. NST)